Among the attributes of the West Bengal chief minister, Mamata Banerjee, that have stood her in good stead is her indefatigability. The unwillingness to be cowed down or even admit the possibility of defeat saw her wage a doughty — and sometimes lone — battle against a ruthless and formidable Left Front for over 25 years. Now, at the pinnacle of her political career, her never-say-die approach has been in ample evidence as she prepares for her most ambitious project that goes beyond the borders of her home turf: to dethrone the prime minister, Narendra Modi, and the Bharatiya Janata Party in the 2019 general election and, in the process, emerge as India’s first Bengali prime minister.

Neither the loftiness of the project nor the roadblocks in her path appear to have deterred her. Last Tuesday morning, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court, hearing an application by the Central Bureau of Investigation, ruled that the Calcutta police commissioner, Rajeev Kumar, was obliged to join the CBI’s inquiry into the Saradha cheating scandal that led to many lakhs of poor and middle-class people of West Bengal and beyond losing their life’s savings. The court further ruled that the Indian Police Service officer’s interrogation would take place in Shillong, a completely neutral venue. The only relief to Kumar, who had been avoiding the CBI’s bid to question him, was the assurance that he would not be arrested and packed off to a prison outside West Bengal. By implication, it also meant that the journey to Shillong wouldn’t automatically necessitate him stepping down from his present post.

In the context of the high drama — accompanied by some 36 hours of saturation television coverage — that was witnessed in the heart of Calcutta from last Sunday evening, the Supreme Court order had a momentous significance. Without saying so explicitly, the top court admitted the right of the Central investigation agency to question an officer of the West Bengal government. It was this right that had been challenged by the chief minister with CBI officials forcibly prevented by the Calcutta Police from serving Kumar a notice to appear before the agency. Banerjee, who sat on dharna in support of her police commissioner, contended that the CBI action violated the federal principles of the Indian State and was unconstitutional. The presumption was that a Central agency could not initiate action without the approval of the state government.

The unilateral action of the West Bengal chief minister was calculated to provoke a constitutional crisis. Assuming that Banerjee thought through her actions before sitting in dharna, the defiance of the Centre was meant to signal four things.

First, it was aimed at signalling to the rest of India, and West Bengal in particular, that the Modi government was past its expiry date and its writ was inapplicable. This is what Banerjee claimed at her mammoth rally on January 19 and this is what she reiterated in the course of her speeches at the dharna — an event she quite grandiosely equated with the freedom struggle against the British.

Secondly, Banerjee may have calculated — although the extent of her premeditation is debatable — that her action would redefine federalism in India so dramatically as to reduce to the quantum of the Centre’s federal rights. Taken to its logically absurd conclusion, it would also imply that an action by, say, the National Investigation Agency, against a terror suspect would first have to secure the approval of the state government.

Thirdly, and keeping her eye entirely on her political constituency within West Bengal, Banerjee’s bid to trigger a Centre-state conflict was a thinly concealed bid to suggest that the BJP was alien to the culture and governance of the Bengalis. For some time, ever since the BJP started grabbing more and more of the anti-Trinamul Congress space in West Bengal, Banerjee has been subtly playing the regional card, with her more vociferous supporters in social media debunking the BJP as an organization representing Hindi domination. She has very carefully put restrictions on public meetings involving BJP leaders from other states, and even suggested that the prime minister was clueless about Bengal’s aspirations.

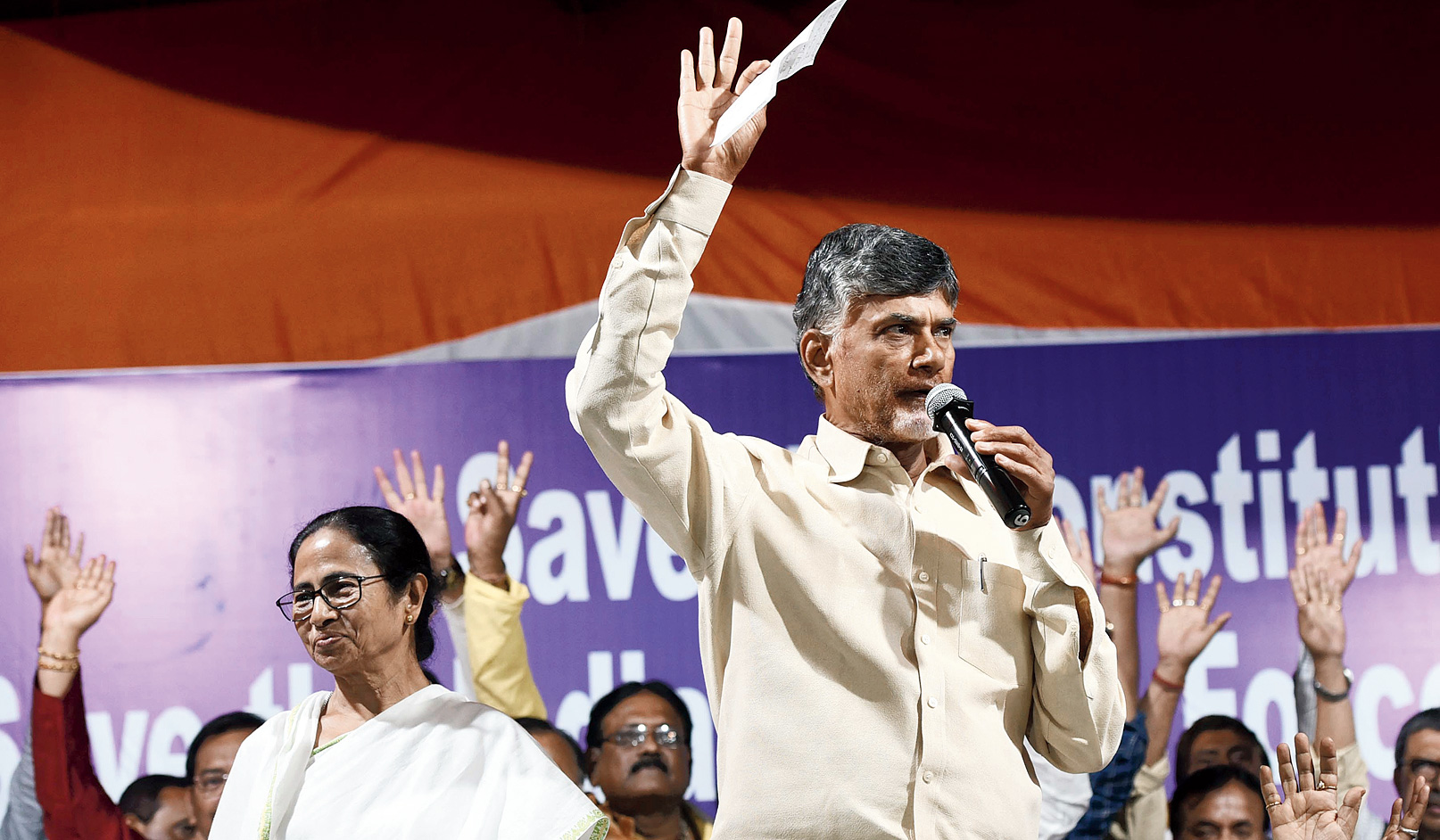

Finally, and from a national perspective, by dramatizing a routine inquiry by the CBI and putting herself at the centre of a contrived battle with the Modi government, Banerjee hoped to consolidate the gains from the United India rally on January 19. At that rally, she projected herself as the magnet of the anti-Modi alliance, the central figure who could bring 23 political parties from all over India in a common endeavour. In effect, she projected herself as the leader of a larger coalition of regional parties — the Congress, while participating, still maintained an arm’s length distance — and a possible prime minister in the event the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance failed to secure a majority. Certainly, last Monday, before the Supreme Court hearing, Banerjee had succeeded in grabbing national attention in a spectacular way and she was even successful in securing expressions of solidarity from a galaxy of Opposition stalwarts ranging from N. Chandrababu Naidu and M.K. Stalin to Rahul Gandhi.

Tragically for the West Bengal chief minister, the Supreme Court order was a bitter disappointment. Although she put on a very brave face and claimed the order to be “moral victory” and persisted with her dharna — converting it into a ‘Modi hatao’ occasion — it was clear that her bid to redraw the federal parameters of India had been thwarted. With this failure, she also exposed herself to the charge — now levelled aggressively by the BJP — that she was using a political slogan to conceal her real intention: to prevent the real truth of the Saradha scam from emerging.

West Bengal’s ruling dispensation has in fact been most vulnerable to charges of both high-handedness and corruption. In both his rallies at Thakurnagar and Durgapur last Saturday — both of which drew impressive and, more important, spontaneous crowds — Modi chose to attack Banerjee for her party’s extortionist practices and corruption. It was thus somewhat surprising that the chief minister chose an issue that was linked to corruption for her grandstanding. It was a high stakes gamble and her failure to get her way — apart from ensuring that the police commissioner isn’t arrested — has put her in a muddle. For the sake of political positioning, she will have to extricate herself from the association with corruption. In time, this may force her to play the regional card more aggressively and even encourage an undercurrent of hostility to Hindi-speaking ‘outsiders’.

Banerjee’s grandstanding was also perhaps aimed at signalling to the bureaucracy that she is steadfast in her protection of loyal officers. Certainly she went far beyond the call of duty in trying to protect Kumar from the CBI. Had she succeeded, she may even have put the residual professionalism of officers at a discount. However, with the Supreme Court also taking note of contempt proceedings against the chief secretary and the state’s director general of police, Banerjee may have ensured a situation whereby officers of the all-India services will now be inclined to play strictly by the book, particularly after the model code of conduct comes into force next month.

Last week, Banerjee played for very high stakes. Perhaps she acted impulsively and out of visceral anger against the prime minister who seemed to be drawing enthusiastic crowds in the state. Whatever her real motives, she will now have to review her options more carefully. This is where her doughtiness and refusal to succumb may come in very handy. As of today she has ensured that the 2019 general election in West Bengal will be bitterly contested.