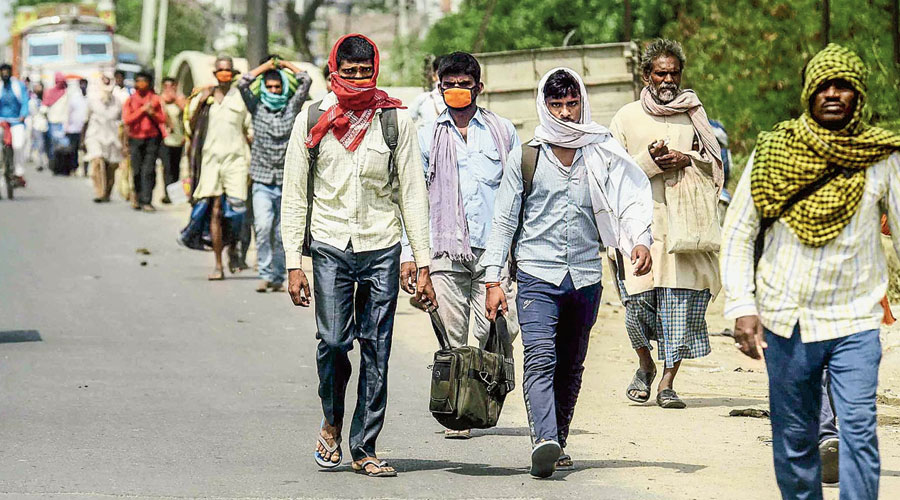

Migrant workers have become symbols of all that is not well with the Indian economy and society. Covid-19 brought their precarious living conditions to light. They have low wages, live in spaces far away from home, and have no job security and little access to government welfare schemes or healthcare facilities; even their identities as citizens are not always documented properly. The Centre had been stalling addressing this problem for a long time. Now, pushed by the Supreme Court, the nation has been promised a comprehensive database of migrant workers in the coming months. The data will enable the set of entitled benefits to flow to the targeted beneficiaries. The database could serve as the beginning of a more comprehensive social safety net for millions of migrant workers. It could also serve as data with which to target specific sets of workers who, presumably, have dubious identities or are involved in criminal activities. For instance, the Tamil Nadu government has recently decided to create a state-level database of migrants who come from other states. This, according to the state government, will help weed out illegal immigrants who allegedly are not Indian nationals or are criminals. It seems that the objective of data collation is not to enable a deprived constituency but, rather, intimidate it. Indeed, given the climate of social exclusion in India, there is no guarantee that the national database, once created, will not be abused too.

This is not to suggest that illegal immigration or crime is to be condoned. However, there are other ways and means available to governments to tackle these issues. Therefore, creating a database of migrants cannot be a justifiable objective. There is another complex issue at stake here. It pertains to the treatment of workers as migrants. They are citizens of India — certainly the overwhelming majority of them — who legitimately travel from their homes to other states to seek employment. The set of people referred to — derisively? — as migrants are poor, vulnerable citizens who ought to be able to access welfare benefits and be provided with security in accordance with labour laws and unemployment support. Much would depend though on how technology is used to give them legitimacy in the era of digital surveillance.