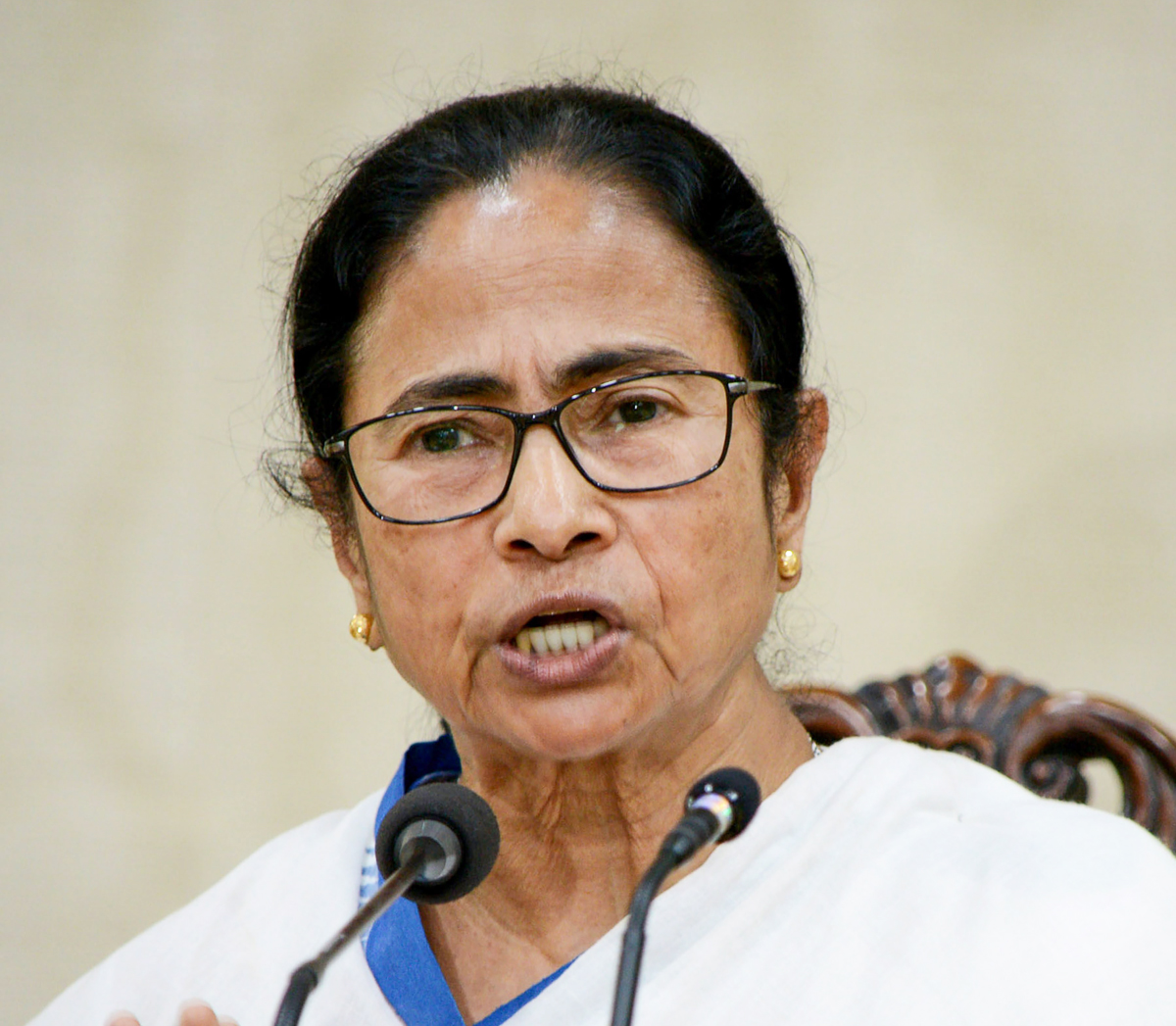

Structure comes as a relief in this unstructured world. Usually. Going by the statement of the West Bengal education minister, the rules notified under the West Bengal Universities and College (Administration and Regulation) Act, 2017 last week are simply a written elucidation of procedures regarding higher education institutions that had remained unspecified since 2017. In other words, the structure underlying the Act is being articulated. The immediately noticeable feature of the rules is the respectfully decorative position being given the chancellor, or governor. The chancellor’s role has always been understood to be honorary; the fact that the rules state that there is to be no independent office under the governor as chancellor to keep in touch with the officials of various universities may seem superfluous. The rules seem to have taken into account the over-activity of the present governor. They ensure that all communication between the chancellor and the universities are routed through the higher education department, including notices of convocations and meetings of university bodies.

An underlying political tension is reflected in the rules that limit the governor to consenting to the names of vice-chancellors brought up by search committees and of governor’s nominees proposed by the education minister. Far more disconcerting, however, is the list of conditions for vice-chancellors. Not only are they to seek the chief minister’s permission to go abroad, for example, they must also deposit written reports of their visits to other universities. Accountability is a good thing, just as structure is. But an excess of either can backfire. The government’s logic, that it funds or aids universities, and can therefore demand accountability, exposes an alarming mindset. One, the government does not ‘own’ money, the money is the public’s. The government is not a creditor. Besides, rules that imply that the trust and respect due to a teacher — a vice-chancellor is a teacher — are absent will just hurt the institutions. No teacher with self-esteem will take the job, no able person will suffer having to justify every step he takes as institutional head. The all-enveloping presence of the government in administrative matters and its attitude to vice-chancellors suggest that the rules are formalizing precisely the kind of State interference that destroys excellence and fairness in education. Too much structure strangles: is that what the state government wants?