Amalkanti is a friend of mine,

we were together at school.

A more prosaic sentence cannot be constructed in English or in Bangla, the language in which it was first written. Nor can a more unexciting statement be thought of. One can read it and be completely unaffected by it. And then wondering if one has missed something, read it again and be even more underwhelmed. But then, the next half-line changes it all:

He often came late to class

Amalkanti has gripped you, quietly but completely. From a pale shadow of no significance he has become a living being, walking slowly into his class, diffident, timid, self-conscious. The rest of that line

and never knew his lessons

turns him into someone whose mind lives in another world, a different cosmos. Till this point the poet has given us Amalkanti in silhouette. He then proceeds to fill that outline.

When asked to conjugate a verb,

he looked out of the window

in such puzzlement

that we all felt sorry for him.

On hearing with deep sadness of the death of Nirendranath Chakraborty, last month, I turned to his “Amalkanti” in Sujit and Meenakshi Mukherjee’s sensitive translation. I could hear the gentle poet recite his work, accentuating words that he chose to accentuate. For instance, if you and I would have said:

When asked to conjugate a verb

he would most likely have said:

When asked to conjugate a verb

Nirenbabu chose his subject, his emphases. I could never understand why where other speakers at a formal event would say ‘Manoniyo Rajyapal’ he would say ‘Manoniyo Rajyapal’. I could not understand why, but I could understand that he had a reason, some reason. Nirenbabu used italics in speech, in the spoken word, not just the written word. Thereby, he drew attention to that which would have otherwise passed unnoticed, or un-noted.

But to return to Amalkanti.

As, grieving for the poet, I read the poem over and over again, something in me recalled another poem I had read a long time ago. (Again, I can hear Nirenbabu say a long time ago, not a long time ago.) This was William Blake’s “The School Boy”:

...to go to school in a summer morn,

— O it drives all joy away!

Under a cruel eye outworn,

The little ones spend the day

In sighing and dismay.

Ah then at times I drooping sit,

And spend many an anxious hour;

Nor in my book can I take delight,

Nor sit in learning’s bower,

Worn through with dreary shower.

It is not my intention here —and a low intention it would be any time — to compare one poet with another except to understand both that much better. And so I am not comparing Nirenbabu’s work with Blake’s, nor the one with the other per se. But this I have to say here that while Blake’s schoolboy is a crayon picture that is essentially about ‘sweet innocence’, Amalkanti is about Blake’s other pre-occupation, experience. And the switch from the scene of classroom innocence to the ‘now’ of lived experience is quick and total. And bare.

He works in a poorly lit room for a printer.

I am not going to give anything more of the poem here and rob the reader of the joy of re-discovering or discovering its layers herself. But by way of a parting moment shared with the poet we need to contemplate Amalkanti, who works in a poorly lit room for a printer. Note, that here is a well-known writer, a man who thinks of and puts together words, writing about an unknown printer who assembles words, presses them onto paper or paper onto them. And in fact not about a printing boss, the owner of a substantial establishment with many employees, attendance and salary-logs, provident fund and gratuity lists, calendars with holidays marked on them. No, not that part-prosperous gentleman but one who works for him.

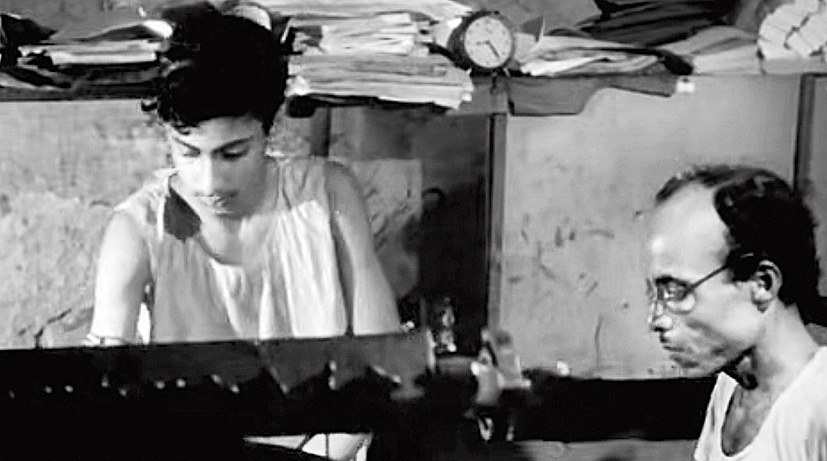

Amalkanti is a denizen of the half-light. A naked bulb battles darkness above his balding pate, a film of dust coats his bifocals at the end of two precarious spectacle-arms of which one has been fastened onto the frame with a coil of string. And printers’ ink, having filled every rift in the leaden mono or lino font that he handles, clogging the ‘o’s, ‘e’s and ‘q’s has moved to his finger-nails, occupying every crack on it, every bend, nail, cuticle. His finger-tips are as leaden as the objects of their attention. He sees rather than reads the words that he assembles, looks at the finished page, measures its margins, fixes the page-number at the top-middle, top-right, bottom-middle or bottom-right as ‘Saer’ has instructed and then closes it, to move onto the next page. He is as removed from sunlight as moss at the bed of a pond. And sunlight is what he wanted to be. To be! Not to be in, but be.

Nirenbabu, sun-crowned in his eminence and his eloquence, recalls his classmate almost exactly as Charles Dickens did in a speech to the Printers’ Pension Society on April 6, 1864 (The Speeches of Charles Dickens, ed. K.J. Fielding, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1960, 323–324,325, 325, cited by Michael Leddy in his blog dated July 8, 2009). Dickens began with: “I do not know whether my feelings are exceptional, but I have a distinct recollection (in my early days at school, when under the dominion of an old lady, who to my mind ruled the world with the birch) of feeling an intense disgust with printers and printing.” And then went on to say: “But this feeling of dislike to the printer altogether disappeared from the time I saw my own name in print. I now feel gratified at looking at the jolly letter O, the crooked S, with its full benevolent turns, the curious G, and the Q with its comical tail, that first awoke in me a sense of the humorous. The printer and myself are, and have been for some time, inseparable companions.” Calling the printer “friend of every man who can read”, Dickens says unforgettably: “Of all inventions, of all the discoveries in science or art, of all the great results in the wonderful progress of mechanical energy and skill, the printer is the only product of civilization necessary to the existence of free man.”

Quite grand Dickens’s unnamed printer is.

Nirenbabu’s Amalkanti is subtler. He is the sunlight that never was. And in writing about him the poet is not talking sentimentally about the printer in his leaden room but about all the et ceteras of life who are cladded in the soot of that abbreviation ‘etc.’. The Latin phrase et cetera means “and the rest”. The et ceteras of life are the uncounted so-called ‘didn’t make it-s’ whose peers are famous ‘made it-s’. They are the taken for granted-s of the world, the tail of any list that gets scrunched up into three letters that are read and not read, allowed to peter out like the last whiff of tobacco from a dying butt.

Kin to et cetera is another Latinism that brings cetera forward: cetera desunt, meaning “that which has vanished” or has been forgotten or elided. It also stands for an incomplete manuscript, a partial narrative.

Nirendranath Chakraborty was a poet of incomplete narratives, not in the sense of half-finished tales but un-concluded aspirations, semi-colons, hyphens with the second part wanting to but not being able to join the picture. He was a poet of the real human situation in which the accentuated is prominent but the unaccentuated is real. And if given the emphasis needed, fulfils that which prints and that which is printed.

RIP Nirenbabu. Or as you would have said rest in peace.