Alfred North Whitehead, the mathematician-turned-philosopher, defined the task of philosophy as one of assembling. For Whitehead, it is the assembling of ideas that forms the task of philosophy. Extending this definition in this article, I would like to assemble not the philosophical ideas referred to by Whitehead but three different combinations of colour and movement. These combinations are available in three principal leaders of the Indian national movement that remain unconnected. Once assembled and well-framed, these can produce a better picture of the Indian national movement. To depict this picture, I take the brush strokes available in Swami Vivekananda, Sri Aurobindo and Mahatma Gandhi.

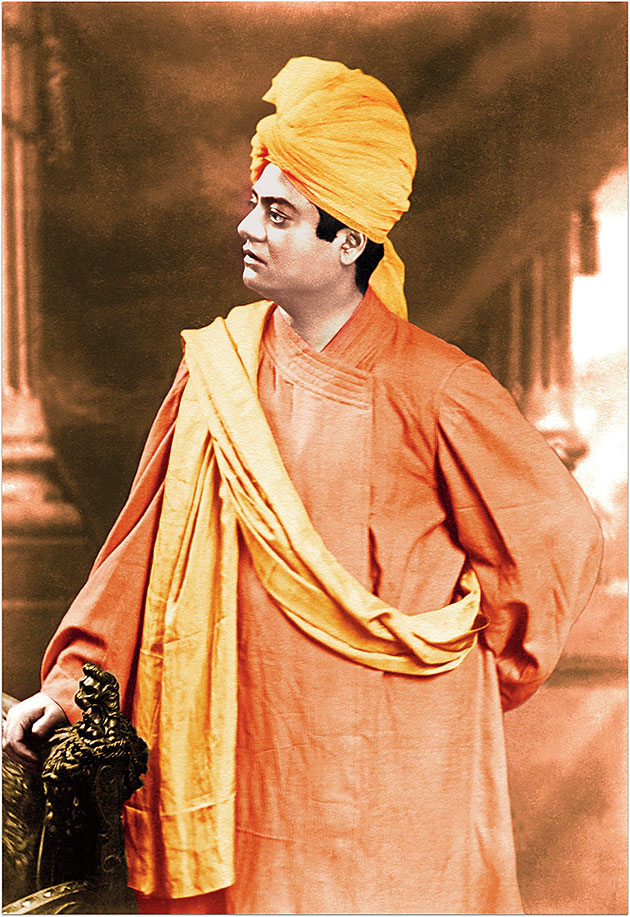

Vivekananda is associated in the popular imagination with the colour, saffron. While he wore white earlier in his life, he subsequently changed to saffron, the characteristic colour of Hindu spirituality. He came to be associated with saffron. He also lived a peripatetic life, travelling not only within India but across continents. This combination of saffron and peripateticism that symbolized his life was also found in Adi Sankara and can be traced further back to Gautam Buddha. Buddha shunned the earlier prevalent practice amongst the sages to retreat to the forest to do penance. Instead, he took to travelling to different places to preach Dhamma. Despite the similarities, however, Vivekananda departed from Sankara’s use of Sanskrit and Buddha’s use of Pali, as dictated by modern necessities. As part of fulfilling this necessity, he wrote and spoke extensively in English, the language of the British. Thus, we see in Vivekananda an inherited past and an adapted present.

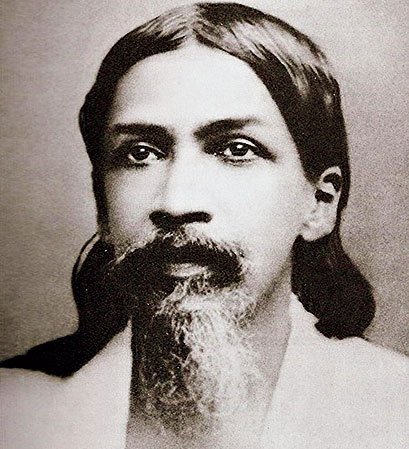

Aurobindo Ghosh Wikimedia Commons

This blend in him of both an ancient religion and contemporary politics proved useful in the Indian nationalist struggle. With Vivekananda, the freedom movement moved for the first time from the regional and local to a national and even an international platform. This broadening of the canvas provided an extended domain to escalate the fight against the British; it established the necessary platform to communicate to the British the claims for India’s independence. This facility contributed, in essential respect, in shaping the nature of the Indian freedom struggle.

A wandering monk clad in an ancient shade of clothing inspires a momentous change. Was it his globally accessible style of communication that made this possible? Or was it the unique blend of the ancient and the modern in him? Or was it both? These are exciting possibilities that can be theorized.

The interactions during his travels gave him first-hand knowledge and understanding of the people of India, their suffering and strength. The colour of his dress also helped him during his journey within India in establishing a connection with the people. He found both internal and external reasons to be responsible for their sorry state — the native rulers as well as the outsiders, that is, the British. Interestingly, criticism of the internal precedes the external in his writings. Before holding the British accountable for the suffering of the people of India, he ruthlessly points out the role played by native rulers and their age-old superstitions and religious practices.

While travelling brought him nearer to the people, his monk’s garb perhaps also kept people away from him, although this distance was governed by respect and devotion. Nevertheless, this combination is novel and epitomizes Vivekananda.

Swami Vivekananda Wikimedia Commons

An entirely different combination is observed in Aurobindo, who considered himself to be completing the mission that Vivekananda had begun. Like him, Aurobindo was wedded to Advaita and was concerned about the British subjugation of India. Unlike Vivekananda, however, he wore white instead of saffron and did not travel but withdrew into seclusion to spend his time in meditation. This withdrawal into deep meditation brought on to the centre stage of the national movement in a significant way the inwardness, particularly spiritual inwardness. The deep meditation added a depth dimension to the campaign. Aurobindo, therefore, had similarities with and also differed from Vivekananda, his guru, whom he never met but whose message he claimed to be carrying forward.

Aurobindo brought to the forefront a different symbolism from history — the rishis and their ashrams. There is politics in this combination too. Despite the radical departure from Vivekananda, Aurobindo continued to write in English like him. Again, by meditating in seclusion, he also created distance, just like his predecessor.

These two combinations of colours and movements paint different pictures in terms of how they recall the past and reveal the present. The combination in Aurobindo can be seen either as adding to or replacing Vivekananda’s. Vivekananda highlights one aspect of history, Aurobindo highlights another.

We find yet another combination in Mahatma Gandhi. Instead of offering a new grouping, this seeks to make creative use of the variables available in the previous mixes. He wore a simple white dhoti or loincloth. The white cloth was not only simple but was also homespun khadi, representing the ordinary people of India. He, too, embarked on extensive travel, on the advice of his political guru, Gopal Krishna Gokhale. His travels branched out in several directions, connecting him with people from different sections of society, particularly from rural India, giving him the direct experience of their life and suffering.

Gandhi selected specific characteristics of Vivekananda and Aurobindo which brought him closer to the people. He adopted the former’s strategy of travelling and the latter’s choice of the white garment. Alternatively, this also helped him avoid the possible distance associated with saffron dress and seclusion. Gandhi’s close connection with the ordinary people of India is highlighted by the Marxist politician-writer, E.M.S. Namboodiripad, in his book, The Mahatma and the Ism. He says that unlike other leaders of the national movement, “Gandhi associated himself with the masses of the people, their lives, problems, sentiments and aspirations.” He adds that there “was not one section of people whose problems he did not study, whose miserable conditions he did not bring out, for whose comfort and solace he did not plead with his audience. It was this that enabled him to attract the various sections of the poor and downtrodden masses.” This approach helped ordinary Indians identify with him and his programmes, and clarified any doubts about his actions and views.

To sum up, Gandhi’s choice to wear white and to travel and mingle with the masses not only symbolized the purity associated with white but it also brought into the ethics of contemporary costume designing the struggles of ordinary people. This alternative way of looking at these thinkers can provide us with exciting new insights into their actions and texts and throw better light on our understanding of the various aspects of India’s freedom struggle. However, such insight can be gained not merely by studying their writings or political activities. A new picture can be created only by finding new connections and assembling elements that have so far remained unrelated. This demands the need to formulate different methods of studying and understanding India, this is a wonder.

The author is on deputation to the Indian Institute of Technology, Tirupati. He teaches philosophy