“We didn’t want this conflict, but now that it’s started it has to end with a sustained period of quiet,” said Mark Regev, the spokesman for Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu. “That can only be achieved by Israel taking out Hamas — their military structure, their command and control.” Or, as the Israel Defense Forces would put it, by “mowing the grass”.

That sounds a bit cold-blooded, but Hamas, the dominant Palestinian organization in Gaza, has an equally pragmatic view of its periodic wars with Israel. Both sides are in a conflict that neither can win conclusively, and so they engage in occasional bouts of attritional warfare.

There are many smaller clashes in between — the border is never completely quiet — but the major ones that last more than a week and kill more than a hundred people are quite distinctive. The 2008 war killed almost 1,400 Palestinians, including 333 children; the 2014 one killed 2,104, more than half of whom were civilians.

Israeli deaths were a tiny fraction of those numbers — 13 in 2008, 73 in 2014 — and the same pattern is being reproduced this time: over 182 Palestinians dead so far, and 10 Israelis. But the disparity is only due to the fact that a modern air force and heavy artillery are much more efficient than primitive, unguided rockets.

Wars are always ‘the continuation of politics by other means’. For Hamas, that usually means upholding its reputation as the most effective Palestinian resistance movement — even though it knows it cannot actually win the war.

For the IDF and the Israeli government, it is generally a matter of “mowing the grass”: repeatedly cutting back Hamas’s military capabilities before they get strong enough to do Israel any serious harm. Since the Gaza Strip is under permanent and almost complete blockade, that threat is very distant, and Israel usually leaves the choice of timing of the next war to Hamas.

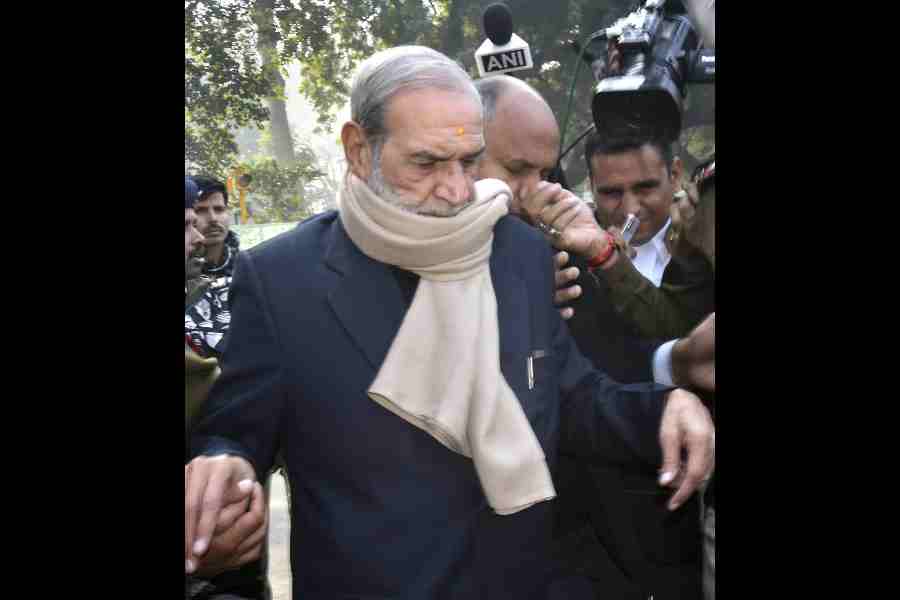

If an Israeli government needs a war for domestic political purposes, it can also provide the necessary provocation for it, and that may be what happened this time. “Netanyahu is exactly where he wants to be, in the middle of a major crisis where you don’t want to change the prime minister,” as a political analyst based in Jerusalem, Mitchell Barak, put it.

Netanyahu was on the way out, but now the coalition talks to replace him have broken down and his most dangerous rival, Naftali Bennett, has crept back to his side. The war will go on until the grass is short enough in the Gaza Strip, and then peace will return for a while. But this is the last time round for this scenario, for technological reasons.

Hamas’s current weapons — home-made, inaccurate rockets — mean that it can only target large areas like cities, so it reaps the blame for targeting civilians. Israel kills many more civilians in practice, but since it uses precision weapons it can plausibly claim that it tries to avoid killing innocent people.

Coming soon, however, are next-generation armed drones that are cheap, highly accurate, and very hard to detect or intercept. We saw early versions of them at work in last year’s war in the Caucasus, where Azerbaijani drones decimated a conventional tanks-and-artillery Armenian army. When Hamas gets them, probably in only a few years’ time, it will face a choice.

It can use them for more effective terror attacks, targeting civilian buses, schools and homes: lots of horror, huge Israeli reprisals, and no political gain. Or, if it’s smart, it can only go after Israeli military targets: tanks, airfields, barracks, fuel storage areas and the like. It gets the moral high ground, and gives Israel a problem that is not soluble by military means.

What political deal might then ensue (if any) is very hard to imagine. However, Israel, after 30 years, when it could just avoid thinking about a future of peaceful coexistence with the Palestinians, will have to engage with the problem again. That would be a good start.