“Aap chronology samjhiye.” The Union home minister’s words, spoken in a different context, can now be justifiably hurled at one of his colleagues, Ashwini K. Choubey, the minister of state for environment, forest and climate change, who said, earlier this month, that the Centre is keen on changing the name of India’s first protected forest from Jim Corbett National Park to Ramganga National Park.

Choubey’s reasoning, as is often the case with his brethren, was a mixture of half-truths and, hence, specious. He said — this is where he mixed up the chronology — that the reserve had originally been known as Ramganga National Park and was then named after Corbett. The truth is that the reserve forest had, in the beginning, been called Hailey National Park after Malcolm Hailey, the governor of the United Provinces, Corbett’s contemporary and a man who shared his peer’s passion for conservation. Independence, which, understandably, kindled the practice of renaming sites associated with colonial figures, led to Hailey becoming Ramganga — but only for a while. In 1956, a year after Corbett’s death far away from India, the tiger reserve was rechristened after him. This renaming was a curious case of reversal, wrote Stephen Alter (In the Jungles of the Night): a space of national importance was being named after a domiciled Englishman at a time when a young nation was energetically jettisoning its links with relics of colonial rule. What must be noted is that there was great public support in favour of the rebaptization, and not just from Corbett’s friends or admirers. Govind Ballabh Pant, Kumaon’s tallest freedom fighter and, subsequently, Uttar Pradesh’s first chief minister, was an enthusiastic proponent of Ramganga giving way to Corbett.

Choubey’s other claim — that he was merely articulating the wish of the local people for another round of name-changing — deserves closer scrutiny too. This is because in spite of the ravages of time and development, Corbett’s name and legacy survive in the much-depleted wildernesses as well as in the surrounding, burgeoning habitations of what is now Uttarakhand, sustaining an allied tourism-based economy that is central to the survival of the local population. (Corbett National Park received 2.84 visitors in 2017-18; the figure was 2.83 lakh in 2018-19.) In fact, the spirit of this public reverence may have been instrumental in shaping the response of the Uttarakhand state government, which stated that it was not in favour of Choubey’s proposal. The state forest minister reportedly added, for good measure, that ‘Corbett’ does not merely signify a surname; it is an expression of ‘national pride’.

This veneration — it would have horrified the self-effacing Corbett — has old roots. Readers, who have had the pleasure of leafing through Corbett’s original writings or, for that matter, Mahasweta Devi’s magisterial introduction to the Jim Corbett Omnibus translated in Bengali, would be knowledgeable about the reasons for this collective admiration. My India — the singular first-person pronoun is important in this context — offers the clearest evidence of Corbett’s organic relationship with, and kindred affection for, Kumaon and its hardy, impoverished, and, sometimes, chequered people. There is Sultana, the forest brigand, of whom Corbett writes: “Society demands protection against criminals, and Sultana was a criminal. He was tried under the law of the land, found guilty and executed. Nevertheless, I cannot withhold a great measure of admiration for the little man who set at nought the might of the Government for three long years, and who by his brave demeanour won the respect of those who guarded him in the condemned cell.” Jostling for space with Sultana on these pages are Budhu and Lala Jee, occupants of contrasting positions on India’s social pyramid — Budhu was a bonded labourer and Lala Jee a merchant — yet bound to each other by Corbett’s benevolence. And who can forget Chamari, an untouchable, whose death — Corbett battled the man’s cholera heroically but in vain — diffused the rigid boundaries of caste, however momentarily, at Mokameh Ghat?

What makes My India striking is Corbett’s unambiguous personal investment in the lives and the welfare of his people. Significantly, Tree Tops, an account of Corbett’s brief brush with royalty, possesses very little of the naturalist’s characteristic warmth, empathy and energy; the narrative is almost sedate in Corbett’s customary reverence for the then princess, Elizabeth, and the Duke of Edinburgh, save for one revealing passage. During a dinner involving the regal dignitaries, a spirit lamp burst into flames. Even as “frantic efforts were being made to stamp out the blaze the African boy who had served dinner unhurriedly came forward, extinguished the flames with a wet cloth… and a minute later replaced the lamp refilled and relit on the table.” It is not difficult to guess with whom Corbett’s sympathies lay on that occasion. In India, his land, this benevolent man was known as the ‘White Sadhu’ in the nooks and corners of his beloved Kumaon.

Yet, Mahasweta Devi informs us that within three months of Independence, Corbett decided to sell Garni House, his family home in Nainital, and move, along with his elder sibling, Maggie, to distant Kenya. Before leaving, he buried his favourite shikar weapons, three rifles and two shotguns, deep in the forest. What made the man — a white man who believed in astrology, a man who knew no home other than India — uproot himself? There are no clear answers to Corbett’s displacement till date. Ironically, Corbett’s uncontested fame as a sportsman seems to have eclipsed other aspects of his intriguing persona reflected in the scale of his conservation efforts in India and, in the dusk of his life, in Africa or his willingness to journey, at the age of 72, in search of a refuge that was not quite home. Is that because Indian historiography is quite often receptive to uncritical veneration but not to objective, if uncomfortable, enquiries into choices made by icons?

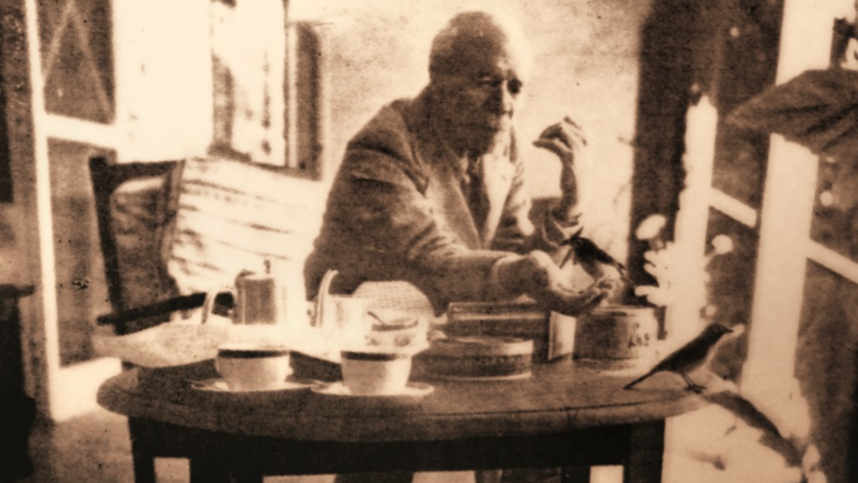

Except for the royal adventure at Tree Tops, very little is known about the everyday life of a reclusive Corbett during his final years in Africa. Mahasweta Devi writes that the aged Corbett was often spotted — alone — on the balcony of the Outspan Hotel, feeding bits of cake and bread to birds (picture). Perhaps that is where Corbett belonged — and wanted to be — in an in-between realm visited by wondrous, wild creatures, away from the oppressive, disappointing bonds with men and nationhood.

uddalak.mukherjee@abp.in