Institutions, empires and socio-political structures emerge, rise and wither away. This holds true of political and cultural theory too. However, there are times when a theory can be influential to the point of changing entire societies and the face of global politics. One such thesis has been the hugely influential, yet extremely controversial, ‘Clash of Civilizations’ proposed by Samuel P. Huntington. The theory, which was developed in the form of an article for the renowned foreign policy magazine, Foreign Affairs, 30 years ago was well received. This led to the book with an extended title in 1996: The Clash of Civilizations and The Remaking of World Order. Huntington posits that the end of the Cold War would see a change in the ideological makeup of the world order and that future conflicts would take place on the basis of cultural factors with religion playing a definite role. In the book, Huntington argued that Western arrogance, Islamic revivalism and Asian assertiveness would influence world politics and how nation-states engage with local and global fault lines.

The theory was ubiquitously accepted in the Western sphere and in some parts of the Asian community, particularly in China. However, the Islamic world was unanimous in its condemnation of the opprobrium that it would be the architect of global Islamist terrorism.

Three decades have passed since the inception of the theory. The key question is this: is world politics still influenced by cultural and religious frictions as asserted by Huntington?

The answer to this controversial — yet important — question is complicated. While globalisation has facilitated the free flow of capital, goods and services, it hasn’t resulted in the free movement of people. This is where the theory becomes highly relevant. The ISIS may have been largely neutralised but religious extremism and sectarian conflict remain at play. This is particularly evident in Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Pakistan, Afghanistan and so on.

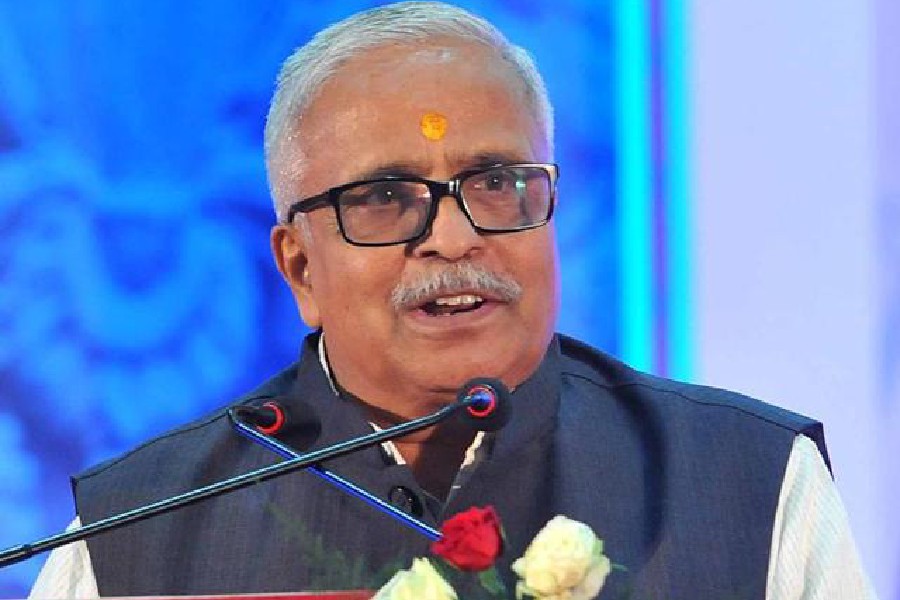

Religion and culture also remain influential in creating fissures in India, Turkey and even the US, the UK and Sweden. The situation in India is particularly interesting with an internal clash of civilization taking place between Hindutva and pluralism.

Karl Marx had dismissed religion as the “opium of the masses”. However, the fact that religion, which was surreptitiously sidelined by ideology during the Cold War era, would make a comeback and would do so violently was visioned before its time by Huntington. The weaponisation of religion and culture for the process of distinguishing between Us/Them, as Robert Sapolsky argued in his book, Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst, has been the direct product of Huntington’s theory.

Thirty years on, Huntington’s theory continues to have its share of critics and proponents. What is necessary is to acknowledge the intellectual depth and the scale of Huntington’s vision. There is a need to acknowledge the possibilities of the theory while propagating the message of amity. The world is facing existential threats in the form of global warming, climate change and the spectre of automation. Should humanity, as predicted by Huntington, waste precious time and energy in religious and cultural squabbles?