The Union government has withheld funds from West Bengal under the National Health Mission for an unusual reason: the health centres are painted the wrong colour.

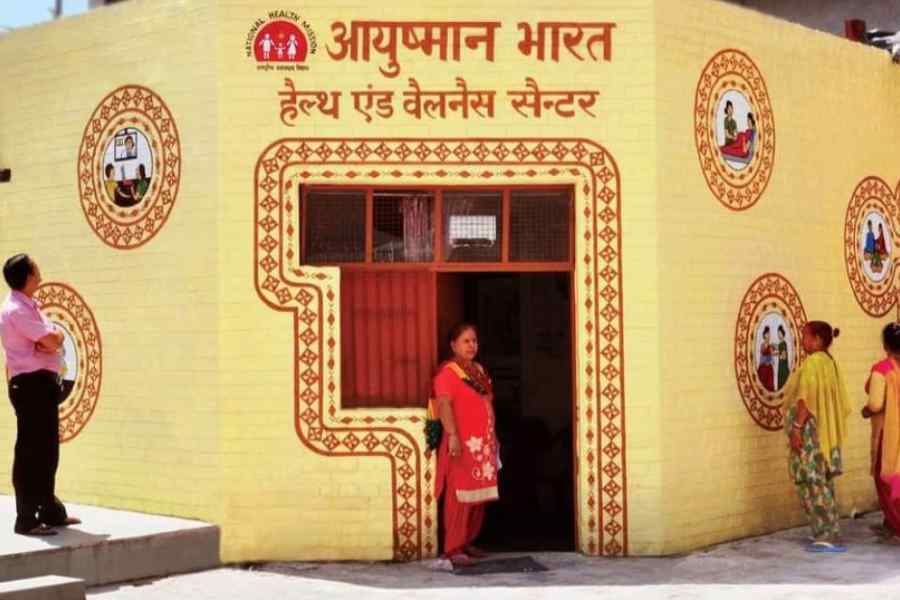

An 80-page document lays down in detail the design, logo, colours and adornments for “Façade Branding” of NHM “health and wellness centres”. The walls must be a “specified shade of yellow”, doors and windows a “specified shade of brown”. No doubt coincidentally, Union government buildings are donning the same colours. So are railway carriages, once blue and white, and still earlier a reddish brown.

As everyone in West Bengal amply knows, our chief minister loves blue and white. In point of fact, the railways adopted those colours before her term in office as railway minister. The sisters of the Missionaries of Charity wore blue and white habits from before Mamata Banerjee’s birth. But in Bengal today, blue and white are indelibly associated with a particular party and personality. Equally, the yellow and brown prescribed by Delhi seems a discreet variant on strident saffron, a spiritual hue glowing with political purpose. Either way, it seems egregious that our highest rulers should squabble like children over their favourite colours when public health is at stake.

The NHM forms the single largest item of the Union health budget. The health and wellness centres are local hubs for immunization, community hygiene, disease control and primary medical treatment. Evidently, the Union government considers destabilizing them a sporting risk to ensure walls of the right tint.

The aesthetic choice is not for medical but promotional reasons, to meet the NHM’s ‘branding’ requirements. Branding is a practice in marketing consumer products. How does it apply to government clinics for the poor? What is being sold?

The answer cannot be medical treatment: sick people will flock to government health centres anyway, unless their faith in them is utterly destroyed. That could happen whatever the colour of the walls. The only other possible commodity on sale is the government itself, hence the ruling party. The branding and packaging are to ensure that the public is suitably grateful to its rulers for the treatment funded by its own money. A carper might protest that this ploy offends democratic norms.

The government in question is based in Delhi. This opens up a hornet’s nest of issues. The funds for this as for most ‘Central’ schemes do not come exclusively from Delhi. In most states, including Bengal, the state government provides 40% of the money. Yet invariably, the scheme is formulated and guidelines cast in stone without any reference to the latter. Those guidelines include items of no practical consequence, like the colour of hospital walls. Any deviation from those ‘norms’ then becomes a weapon to punish a state for voting another party to power.

Needless to say, those other parties recognize the ploy for what it is, a gambit for political publicity, and wish to play it for their own gain. They lay out a counter-arsenal of colours, logos, designs and slogans. In the ensuing brand warfare, the actual ‘products’ on offer — health, education, welfare, the entire economy — are lost to view, just as food or fashionware suffers in quality if the producers bank solely on advertising to trap customers.

Branding can touch rarer heights. We pay extra for garments bearing the maker’s logo, though it’s they who should pay us to display their brand. So are government schemes, using people’s money for people’s welfare, presented as the ruler’s munificence. Googling the initials ‘PM’, I hit thirteen different schemes with those magic letters on the very first page. A complete list would be longer still. It would include long-standing services tweaked lightly or not at all. PM Poshan 2.0, for instance, is simply the school mid-day meal scheme, operational since 1995.

Such ‘branding’ might appear a harmless ego trip. But it has two consequences silently corroding the foundations of our polity. First, it reduces the entire government to a publicity machine. The signboard becomes the sign, the signifier, which in turn becomes the thing itself. The wrapping does duty for the contents; the practical gain (or, possibly, harm) disappears in a fog of rhetoric. The benefit to citizens need not be real as long as they can be induced to believe so, or at least bullied into saying so. Many will readily fall in line because they want to believe. How much pleasanter to admire yellow and brown (or blue and white) walls than to submit to painful surgery or bitter pills — until it becomes a matter of life and death.

The other damage is that citizens of a democratic State are reduced to pliant beneficiaries of authoritarian rule. Public funds are dispensed as not only partisan but personal bounty, stamped with the leader’s identity and trumpeted from billboards. The Union finance minister once demanded that ration shops should display the prime minister’s picture as the giver of free foodgrain. Hence too, the ruling party can astonishingly claim virtue for having dispensed free Covid vaccines. Which government in the world did not? And was the cost met from any source other than public money?

This unedifying syndrome spawns the notion of the rewdi, the alleged ‘freebie’, vilified yet opportunistically distributed by the ruler and obeisantly received by the subject. With it goes the demeaning appellation of labharthi, defined not by what is given but how it is given. The labharthi is a creature without entitlement, a receiver of unmerited bounty, not a participant in a democratic process of resource distribution.

One might investigate how many health centres in ‘double engine’ states have yellow walls. If they mostly do not, we may ask whether their grants too have been withheld. If they do, it prompts the deeper question of what this repainting cost the nation, and whether the money was not better spent on actual medical services. Such inquiries are misguided. The intention is not to improve the citizens’ health but to condition their minds. Beyond all else, we are votaries of the spirit.