This year marks 35 years since the publication of Salman Rushdie’s controversial novel, The Satanic Verses. In October 1988, India became the first country to ban the book when the Rajiv Gandhi government was petitioned by the Muslim parliamentarian, Syed Shahabuddin. The Rushdie affair stands out in public memory because of the public burning of the book in the northern England town of Bradford in January 1989. On February 14, 1989, the Iranian spiritual leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, issued the infamous fatwa calling for Rushdie’s death. This made the Rushdie affair into an international and diplomatic event. It also resulted in the word, fatwa, being included in the English lexicon. The word has since mostly been understood as a binding legal diktat, when in classical Islamic jurisprudence it may merely mean a non-binding legal opinion.

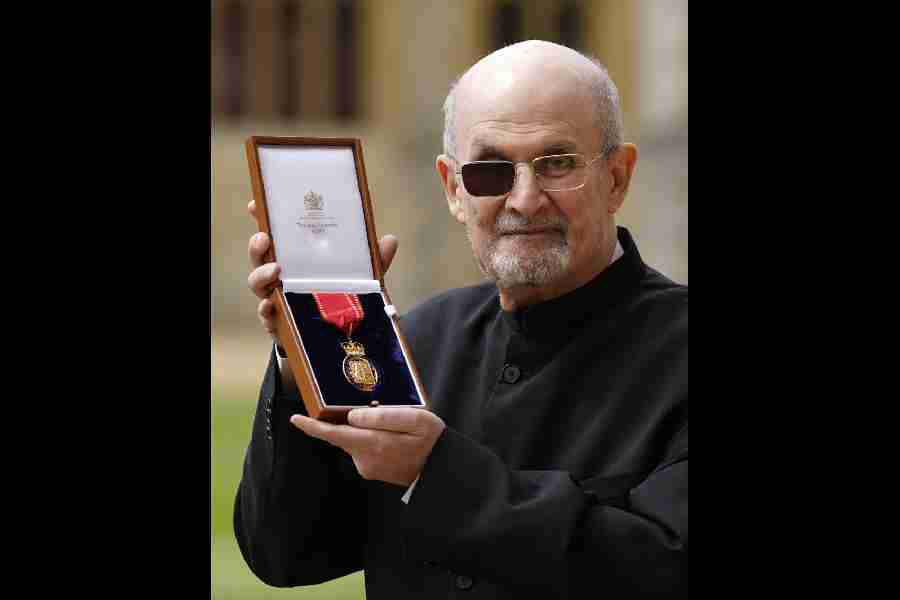

The Rushdie affair never seems to go away. In August 2022, Salman Rushdie was injured in a stabbing incident by the Lebanese-origin Hadi Matar in New York state, resulting in Rushdie losing vision in one eye. Rushdie himself has, over the years, become a figure associated with a valiant and principled defence of free speech. He

has refused to be cowed down by those seeking to silence him.

Despite the defence of free speech mounted by Rushdie and his peers, the principle is even more precariously positioned today than it was three and a half decades ago when the Rushdie affair first broke out. This may suggest that grandstanding defences of free speech have had the opposite effect. Ironically, even as the public burning of The Satanic Verses was denounced in the Western media as medieval and reminiscent of the Nazi era, there have been a spate of public burnings of the Quran in Europe recently. The problem of Islamic fundamentalism became further entrenched in the Western political imagination as the Rushdie affair was followed by the US-led war on terror.

Among the many books written on the controversy was Kenan Malik’s From Fatwa to Jihad. Malik is otherwise a balanced and sensible political commentator. But the title of his book suggests that it is only a small step from fatwa to jihad to Islamic terrorism and, beyond, to a sharia-compliant and enforcing State. The reinforcement of an exclusive and uncritical association of Islam with terrorism seems then to be a fall-out of the Rushdie affair. This unfortunate association has been amplified by other influential members of the British literary establishment through their writings, such as Fay Weldon, V.S. Naipaul and Martin Amis, and, at times, by their defence of Rushdie.

The Rushdie affair has become extremely important in terms of its political and

philosophical implications for societies of the late 20th and early 21st centuries as they contend with fundamentalism, terrorism, Islamophobia and free speech. A historical parallel can be drawn with the Dreyfus affair of France in the late 19th century in terms of its implications and the anti-Semitism that it gave rise to in France and other parts of Europe.

There are lessons to be learnt from the Rushdie affair. One big lesson for the Muslim side is to prioritise free speech, the lack of which must be acknowledged as a pressing problem. For the West, the Rushdie affair offers a lesson in how not to defend free speech. Free speech cannot be defended by merely asserting its significance ad infinitum. Free speech requires enabling conditions, such as ensuring education remains a public good, a press free from the malign influence of media barons, and prevention of the internet and the social media from becoming commercialised repositories of hate speech in the guise of free speech.

Remarkably, the more vociferous voices have been in the West in making the case for free speech, quite often against Islamists, the more the principle has been undermined. The clue to this curious puzzle of wasted efforts in the cause of free speech could lie in the evisceration of every single one of the enabling conditions just mentioned.

Amir Ali teaches at the Centre for Political Science, JNU