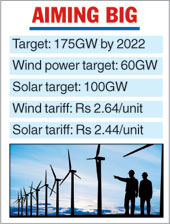

India has $53 billion stressed debt or non-performing assets in the power sector mostly comprising thermal or coal power plants. While the sector is reeling under NPAs, renewable energy has emerged as a sustainable alternative to thermal power. The country already has the world’s fifth-largest renewable energy installed capacity of 70 gigawatts, comprising 22 GW of solar and 35 GW of wind energy, which is expected to increase to 140 GW by 2023, putting the total capital cost at more than $100 billion. With large capital at stake, investors and lenders in renewable energy can take a cue from the power sector to avoid the NPA redux.

How is rule-based lending creating industry-wide risk in renewable energy?

Most of the renewable energy assets in the country are being financed under 70:30 rule-based lending, which translates into debt financing of $70 billion for $100 billion of renewable energy projects. This is creating an industry-wide risk in the form of overleveraged projects because of two reasons. First, the project costs are changing rapidly and are not transparent. The intra-year variation in solar module prices can be as high as 30 per cent. Further, collusion of project developers with suppliers of solar modules, inverters and structures to inflate project cost is also not uncommon. Second, the project simulations rely on satellite-based irradiation data, which is up to 20 per cent higher than the actual irradiation at several project sites in the country; this alters the project economics.

A recent transaction in the market illustrates the point where a leading financier funded a rooftop solar project at a stated cost of Rs 55 million/megawatt while the actual cost incurred by the project developer was only Rs 40 million/MW. At 70:30 debt to equity ratio, the project qualified for the debt financing of Rs 38.5 million, which was 96 per cent of the actual project cost, thereby reducing the equity contribution to just Rs 1.5 million/MW. In investment parlance, this is known as ‘skin in the game’. When a project developer no longer has skin in the game, he may have no or little incentive to run a renewable energy project for 25 years when he has already recovered the return on his investment upfront. Such projects in years to come may turn into stressed assets.

Now, private investments in renewable energy may slow down. Let us see how.

Businesses that make money attract more money. While overleveraging a project to generate high equity returns may seem like smart business (one that makes money for promoters), it is unlikely to create profitability or surplus for the renewable energy company itself. More important, it may involve unethical (not necessarily illegal) practices of overstating project costs to lenders and so on. In the current scenario, at stated costs and prevalent tariffs in the rooftop solar market, most of the projects will struggle to generate more than 8-10 per cent equity returns while most investors expect equity returns of more than 15 per cent. If the previous rounds of investments are not able to generate the desired returns, the new investments may dry up.

It seems sensible that cash flows should drive project financing instead of thumb-based rules. Many traditional financiers dealt with the issue of promoters’ skin in the game by funding projects based on collateral (property and so on). However, this discourages the project finance industry. Alternatively, the power purchase agreements provide a transparent way of estimating the eligibility of debt financing for a project based on debt service coverage ratio. This requires a strong know-how of the renewable energy business to aptly capture the risks which can impact the cash flows and to build sufficient buffers to deal with the volatility associated with the same. Financiers also need to develop a strong business perspective to obtain reliable information on project cost on an ongoing basis. This may include developing relationships with suppliers such as that of photovoltaic modules, inverters, and mounting structures.

The renewable energy industry will thrive but needs to tread with caution. It is likely to see the churning that emerging industries go through. Businesses around stressed renewable energy assets may emerge at two levels. First, companies that may take over stressed assets at discounts with the intention of restoring optimal generation levels. Second, it will in parallel create a market for financiers to facilitate restructuring of stressed assets. Unlike thermal power, renewable energy faces far fewer risks in restoration and restructuring. For instance, it does not face the resource-supply issue which coal-linkages do. Hence the deep haircuts or losses that the banks face in thermal power may not be required in renewable energy. Once the renewable energy assets have been through a stressed credit cycle, the market may pave the way for financially sustainable businesses. Unlike thermal power, renewable energy will thrive but needs to tread with caution on aggressive expansion with government enabled financing.