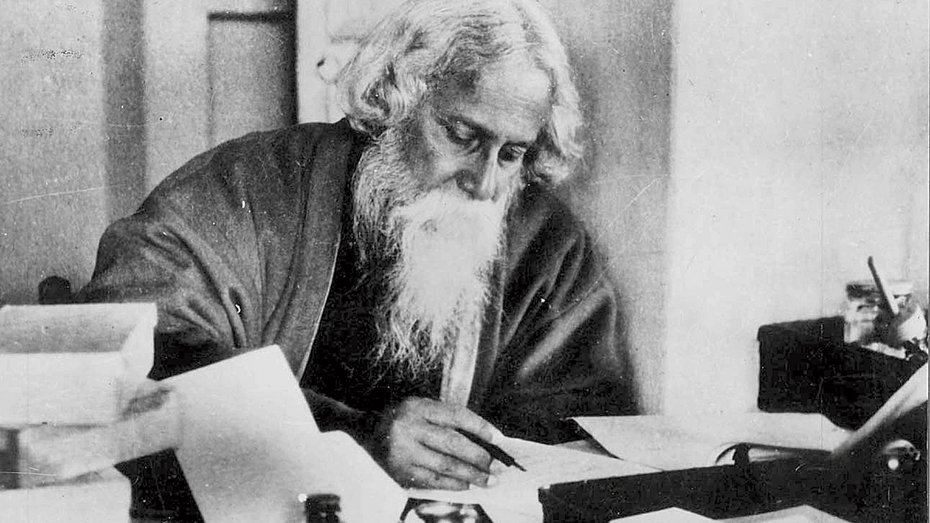

When I interviewed the celebrated Indian modernist artist, Ram Kumar, I was touched by his candour when he admitted, almost apologetically, that museums in the West did not readily acquire works by Indian modern and contemporary artists because they were considered derivative. I got another perspective of this exchange of ideas and aesthetics between the West and India at the recent exhibition at Belvedere House, Calcutta, of the numinous Impressionist paintings on cardboard by the mother-daughter duo, Elizabeth Sass Brunner (1889-1950) and Elizabeth Brunner (1910-2001), of Santiniketan and their guiding light, Rabindranath Tagore.

I was struck by the powerful effect the poet must have had on contemporary Western thought. For the Brunners had sailed all the way to India way back in 1930, their lodestar being a spiritual dream of Tagore. But as the seminal book, A Mediated Magic: The Indian Presence in Modernism 1880-1930, reveals, Tagore was not the only one to hold the fascination of thinkers, artists, writers, designers, psychologists, dancers, choreographers and musicians in the West; the whole gamut of Indian culture did so. The book, published by Marg and edited by Naman P. Ahuja and Louise Belfrage, analyses why intellectuals and artists of the West, disillusioned with materialism and devastating wars, sought succour in India’s putative spiritualism, a typecasting that it was never quite able to get rid of, or the adherence of which it was, probably, partly responsible for.

In a fascinating series of essays, we discover how the explosion of contemporary research had facilitated the percolation of ideas from India to the West. Sonu Shamdasani writes about Carl Jung’s immersion in Indological texts and myths, his collaboration with Indologists, how he used his readings to unlock the keys of symbolism and his visit to Calcutta in the 1920s. The sumptuous illustrations such as the brilliant pages from Jung’s illuminated leather volume of selective fantasies coupled with interpretative commentaries in an ornate gothic script, and Swedish painter Hilma af Klint’s giant, hitherto-unseen abstract works executed under the directions of a spiritual guide named Ananda have enriched the volume. The latter happened to be the first transcriber and interpreter of Buddha’s words. Readers will recognize in him the monk who abjured untouchability in Rabindranath’s Chandalika. Is this connection a mere coincidence? Be it the Bauhaus exhibition in Calcutta in 1922 or his experimentation with craft and education, Rabindranath was a key figure of this period.

Captions loaded with information, innumerable rare photographs, playbills, drawings and other documents bring the pages alive. Think of the sketch designs for a 1910 production in Moscow of Kalidas’s Shakuntala that go with Kalpana Sahni’s essay on the “rejected histories” of modernism to elaborate on the impact of non-European cultures on the movement. The Theosophical Society — its members believed that India was the cradle of both Western and Oriental religions and philosophy — with Madam Blavatsky and later Anne Besant at its forefront, acted as a “conduit of knowledge” that had a far-reaching effect on not only af Klint but artists like Wassily Kandinsky, Frank Kupka and Piet Mondrian. The extent of the influence can be gauged when one realizes that Carnatic music was studied in the West then, and British composers like John Foulds drew on Indian classical music.

In Michel Carné’s Les Enfants du Paradis, the courtesan, Garance, drapes her bed sheet across one shoulder and exclaims that it is Indian. But the colours of Ind permeated well beyond superficialities. Leading designers and choreographers like Nijinsky, Pavlova and Léon Bakst interpreted South Asian dance in their own way. This encounter led to a better understanding of the “other” and of ourselves as we moved into the modern age.