From the time of publication of Man-Eaters of Kumaon in August 1944, the name of Jim Corbett has been synonymous with India’s wildlife. He was no trigger-happy hunter. He labelled the tiger “a gentleman of the forest” who turned to killing cattle or humans out of dire necessity.

Yet wildlife aficionados have a hero of their own. In his own writings, Corbett had hailed this forester as a pioneer of wildlife photography in India. This was a man who had served in the First World War on the Northwest Frontier and put away his guns (except for game meat in the open season). Instead, he had sought out the tiger not with gun but with camera.

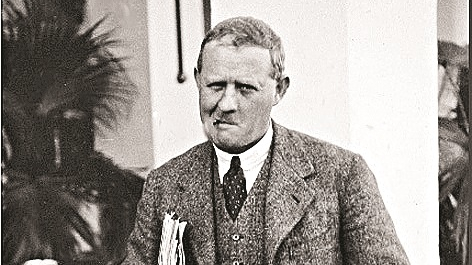

Frederick Walter Champion (picture) served in UP for over a quarter century. Like Corbett, he left for East Africa soon after Indian Independence. He found it easiest to photograph tigers by trip-wire photography. The tiger tripped the wire on its own path and took its own picture. The book, With a Camera in Tiger-Land, published in 1927 had no precedent.

Not only did he photograph tigers but he depicted them in their natural state, not fleeing beaters or about to be shot dead by sport hunters. Tigers remained elusive. Of the 200 camera traps placed by Champion, tigers came by on only 18 occasions. In all, he had 11 shots of nine individuals, but this was enough to prove how each animal had distinct stripe patterns.

This was a path-breaker in every sense. Over the last three decades, scientists the world over working with far more advanced cameras and aided by software can tell a tiger by his or her stripes. It is now a widely used technique worldwide, and its pioneer was a deputy conservator of forests nearly a hundred years ago.

Away in East Africa, Champion missed India and its tigers. Writing to the British tea planter and naturalist, Edward Pritchard Gee, he confided that “Animal photography here is too easy.” Tired of taking photos of lions, “which completely ignore motor cars” (in the national parks), he longed “for my friends, the tigers of India, which can at no time be photographed easily.” The dense foliage and the quality of light made taking quality photographs difficult.

By this time, wild animal photography was being taken over by bigger players like the American company, Walt Disney. Colour photographs were to replace the black-and-white images that Champion had excelled at.

Wildlife protection had had an early start in colonial Africa as opposed to British-ruled India. The Kruger National Park in South Africa and Parc National Albert in the Belgian Congo were established in the mid-1920s. By then, the French already had a national park in their North African possessions. India’s first national park, Hailey, was established in 1935.

The Shivaliks where Champion had served with distinction contained the shooting blocks of the governor-general. The viceroys, down to Mountbatten, had taken shikar very seriously. Both Linlithgow and Wavell had their tiger shoots organized by none less than Corbett. But Rajaji, the first Indian governor- general, was disapproving of hunts. In 1948, a sanctuary was carved out of the shooting blocks in the Shivaliks.

Champion was concerned about the depletion of tigers by sport-hunting. His response was to allot shooting blocks where there were likely to be no tigers for hunters to shoot. The law now stepped in. Rajaji, as the sanctuary was then named, is now a vastly expanded tiger reserve, a safe haven for fauna as much as for flora.

F.W. Champion died in 1970 aged 76. By then, the tide had turned. In January that year, acting on a letter received from Loucia Stephens-Holmberg, a Canadian citizen living in Montreal, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi expressed shared concerns and promised “determined actions to prevent encroachment and also find ways to encourage wildlife to grow”.

In September 1970, the Indian government banned the export of tiger skin. It marked the end of an era. An obituary of Champion appeared the same month. The Commonwealth Forestry Review noted how, “Most young forest officers in those days were keen on shooting big game,” but Champion spent spare time trying to film the elusive tiger. He was commended for being “the first person to get really good photos of tigers in their natural wild state.”

The last qualification is important. There were pictures galore of animals killed in shoots. Of course the forester-naturalist was not alone in stalking animals with a camera. There were others treading a similar path.

The Swedish ornithologist (and Nazi fellow traveller), Bengt Berg, filmed tigers in Kanha and rhinos in Jalpaiguri but his book, Tiger und Menschen, was published in 1935. The Calcutta-based businessman and photo-shop owner, Arthur Musselwhite, brought out Behind the Lens in Tiger Land two years earlier.

Yet the black-and-white images of a tiger padding down a forest path by Champion stand out for quality. These are wild animals at peace going about their daily life, portraits that stand out almost a century on. His second work, The Jungle in Sunlight and Shadow (1934), is a book in its own class. It explored the world of the forest beyond the tiger. Champion was an acute observer of creatures great and small. His images of the nocturnal ratel or ‘honey badger’ and of the now endangered scaly ant-eater or pangolin were equally notable. His record of the huge herds of swamp deer in the Raja of Singahi’s hunting ground is all that remains as the grassland and the deer have long vanished. He likened its cry of “Ring-hon” to a sound “exactly resembling the drone of a Highlander’s bagpipes”. This was a private reserve where both Champion and Corbett pursued the already rare deer with cameras.

Right to the 1970s, many animals were classed as vermin and shot, snared or poisoned with rewards being given to those who dispatched them. Champion was unusual in his sympathetic accounts of the jackal, wild dog and leopard. “Every creature”, he wrote, “has its place in nature’s balanced scheme of wildlife.” In this, he was way ahead of changes in the United States of America or South Africa where park rangers were still hunting down predators at the time. He argued that predators were not cruel and bloodthirsty and killed mostly for need. Best to leave them be.

Champion believed his department to be the best equipped agency to protect nature. But among foresters he spoke out in favour of stricter protection, especially of the fauna. Interestingly, his brother, Harry, also a forester, was accomplished at botany and co-authored the standard book on forest types of India.

Champion’s legacy has undergone a revival. Project Tiger’s first director, Kailash Sankhala, quipped had tigers been given a vote, the Corbett Park would be renamed after the real hero! In his book, Champion as early conservationist was without peer. Of course, such renaming may do less than justice to either man. The challenge is of keeping these living landscapes intact. The web of life enriches humans, making civilizations possible. Those black-and-white images were a celebration of that awareness.

The author teaches History and Environmental Studies at Ashoka University