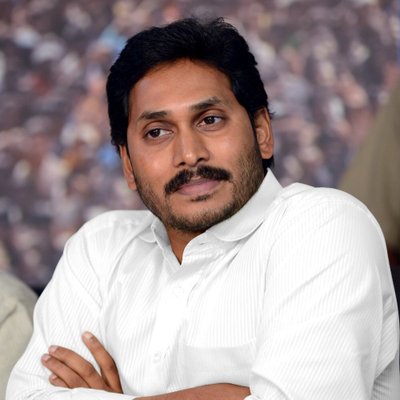

New India has been failing consistently when it comes to augmenting the vision of the founders of the Constitution. Some of the pivotal foundational values of the Republic — pluralism and equality can be cited as two examples — have been weakened considerably in recent times. Elected dispensations are also busy hacking at the roots of other principles. Freedom of the press — the Tebbit test of a democracy — had not been specifically mentioned in Section 19(1) of the Constitution but that may only be because B.R Ambedkar, one of the architects of the Constitution, believed that the media’s right to air their opinion is concomitant with the right of the citizens to express themselves freely and fearlessly. The minders of New India have let Ambedkar down in this respect as well. Andhra Pradesh, which has elected Y.S. Jaganmohan Reddy’s YSR Congress to power, has given its nod to an earlier provision that empowers secretaries of government departments to file complaints against the media for publishing defamatory news. Mr Reddy’s government has assured the media fraternity that it is committed to upholding the rights and freedoms of the fourth estate. That there have been few takers for such an assurance may have to do with the fact that defamation — a legacy of colonial jurisprudence — has always been a reliable stick in the hands of the State to beat the media with. Ambiguities exist in the interpretation of defamation: thin-skinned governments are ever willing to blur the line between legitimate criticism and defamation in a bid to stifle dissent. The media’s right to be critical of a government or a specific department should be absolute in a democratic system of governance. Moreover, statutes exist to restrain the press from indulging in vendetta. Yet, Mr Reddy has felt the need for an additional leash to tame the media.

The country, unsurprisingly, has been faring poorly in the global press freedom index. Its current rank is 140. Yet, it would not be fair to point fingers at authoritarian dispensations only when it comes to the erosion of the edifice of the media in India. The media as an institution has also been complicit in its own undoing. One of the reasons being attributed to Mr Reddy’s excess is that the media in Andhra Pradesh has, for long, been divided on the basis of political allegiances. Mr Reddy, now ensconced in power, believes that this is the best way of getting back at his critics. Fairness must be integral to the media’s conduct. Otherwise, the consequences — Andhra Pradesh has shown — could be foul.