If in politics, as in life, nothing succeeds like success, the converse may also be true. In the aftermath of last week’s drama in Maharashtra, there is a widespread perception that the Bharatiya Janata Party bit off more than it could chew and ended up with a bout of severe indigestion.

There was undeniably a lot of sneaking admiration for the way in which last Saturday’s early morning swearing-in of Devendra Fadnavis was managed. It caught most people, including those in the BJP, by complete surprise. The admiration was all the more because the party also exposed the underlying fissures in the Pawar family. Where the expectation was that the Shiv Sena — co-travellers in the triumphant march of Hindu nationalism — was perhaps most vulnerable to the elder brother’s poaching, Ajit Pawar’s defection suggested that the over-pragmatic Nationalist Congress Party was not entirely in the iron grip of Sharad Pawar.

Alas, for the BJP, the victory turned out to be too short-lived. The NCP, Congress and the Shiv Sena which were on the cusp of entering into an unlikely alliance, quickly united against a common foe, marshalled their forces and, with some help from the Supreme Court, ensured that the BJP assault ran out of steam. The belief that the Union home minister, Amit Shah, was a larger-than-life Chanakya who could undertake near-impossible political missions with resounding success, was also punctured. The government of Narendra Modi was shown to be strong, but not all that mighty. It, too, had its limitations.

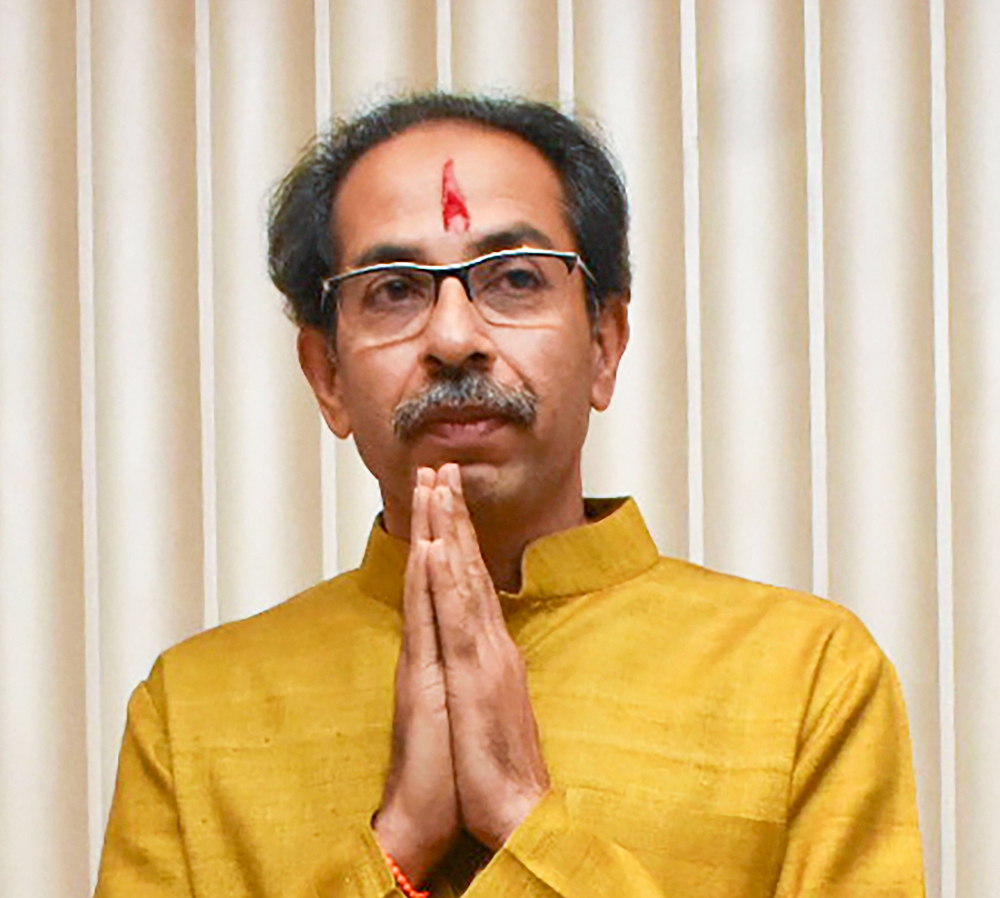

Of course this is not to suggest that Maharashtra will now have a stable government for the next five years headed by Uddhav Thackeray, the first Shiv Sena chief who will have power with responsibility. There is no doubt that the sustained bid by the BJP to break the NCP and challenge the integrity of the Shiv Sena has prompted a contrived solidarity among the three parties that make up the anti-BJP alliance. However, this is certain to be a temporary bonding.

The contradictions that exist between the ‘secular’ Congress and NCP on the one hand and the ‘Hindutvavadi’ Shiv Sena on the other cannot be brushed under the carpet for too long. At the constituency level these parties have fought each other bitterly and they have different support bases. The NCP is prone to celebrating its pragmatism and can happily cohabit with either the Congress, or the Shiv Sena and even, if the need arises, the BJP. Indeed, at one time the possibility of the NCP joining the Modi government seemed real.

The Congress, however, has a very different self-image. It took a great deal of agonizing and persuasion by Sharad Pawar before Sonia Gandhi could agree to her party joining the alliance and accepting the Sena chief as the chief minister of a coalition in which the Congress was a partner. In large parts of the country, the Congress has become disproportionately dependant on Muslim support for its very existence. Teaming up with the Shiv Sena runs the risk of its Muslim support base being eroded. The Congress, for example, has reasons to be worried by the defeat of its candidate in the Kishanganj by-election in Bihar to the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen led by Asaduddin Owaisi. The AIMIM has already made some inroads in Muslim-dominated pockets of Maharashtra and, if the trend accelerates after the alliance with the Shiv Sena, the Congress may well find itself in grave difficulties. Whether the compensatory advantages of being in power in India’s most prosperous state is sufficient to buy the party some breathing space to overcome the devastation of the general election of 2019 is an open question.

The Congress, of course, is not the only constituent of the so-called Maharashtra Vikas Aghadi that will have to grapple with the political fallout of the realignment in the state. There is some visible elation in the Shiv Sena at a Thackeray sitting in the chief minister’s chair, not least because it is viewed as a vindication of its leader’s insistence that the party must get its due and regain its leading role in the state — something that the BJP refused to concede. There is also a quiet belief that once in the top position, it will be difficult to dislodge Uddhav, at least in the next five years. Therefore, even if there is a fallout among the three parties and the Sena rejoins its alliance with the BJP, the price for it will be the continuation of the existing chief minister. This is what happened in Bihar after Nitish Kumar and Lalu Prasad fell out yet again after winning the assembly election in 2015.

However, all that is in the future. For the moment, the Shiv Sena will have to explain its latest realignment to its voters. In particular, it will have to clarify — not least to the Congress and NCP — whether or not its position on Hindutva has been affected by the alliance with the Congress and NCP. The Sena has got its ministers in the Modi government to resign and now sits in the Opposition benches in Parliament. That’s understandable. The bigger question is how the Sena members of parliament will vote on issues that have an explicitly ideological dimension as, say, the citizenship (amendment) bill that its partners seem determined to scuttle at all costs.

I don’t think that the Sena’s awkwardness over the new realities is pre-determined. What will warrant closer scrutiny is any move by the party to make a shift from being a party upholding the Shivaji and Maratha manoos inheritance of Bal Thackeray to becoming a more ‘normal’ regional party. Ideological shifts have to be deftly managed and Uddhav Thackeray’s leadership skills will be tested in the coming days.

Finally, the BJP too will have to confront some of the consequences of its failure to mount a successful coup. Ever since Amit Shah assumed charge of the party’s political management, the relatively cautious style of Atal Bihari Vajpayee and L.K. Advani has been replaced by an aggressive orientation centred on the belief that the party’s opponents must not be conceded an inch, even if that involves testing the principles of fair play. As opposed to the time in the 1990s when an ideologically assertive BJP basked in ‘majestic isolation’ and Advani conceded the party lacked a “killer instinct” to grab power, today’s BJP is far more adept at taking full advantage of its status as the party in power at the Centre. Its swift actions in Goa and Haryana prevented alternative formations from materializing after inconclusive election results. This approach didn’t work in Maharashtra, just as it failed to click in the immediate aftermath of the Karnataka election. In Karnataka, however, the party is back in power and there is talk of H.D. Kumaraswamy’s Janata Dal (Secular) either joining the government or extending it support.

The experience of Karnataka may be instructive in the case of Maharashtra. It is unlikely that the BJP is going to review its aggressive ways. What is more likely is that it will chip away and use its clout at the Centre to create fissures in the Thackeray-led government. It is the combination of ideological commitment and political flexibility — what is glibly referred to as the Chanakya approach — that will remain the hallmark of the Modi-Shah approach to politics. For them, Maharashtra is a setback but it is not likely to be perceived as a defeat.

What is happening in Maharashtra is a game of patience aimed at seeing who has the last laugh.