The big bang began with the baozhu. Almost two hundred years before the birth of Christ, the Chinese — the progenitors of many human inventions — had committed the original sin: they heated bamboo and discovered, much to their amazement, that the heat caused the material to explode — baozhu, quite aptly, means ‘exploding bamboo’ — with a flash and a deafening noise. Since then, for over 2,000 years now, India and other parts of the world have been paying the price for the unceasing enchantment with the baozhu’s sophisticated, raucous descendant: the modern firecracker.

The price, of course, varies, depending on the setting. Each year around Diwali — firecrackers worth approximately Rs 1,500 crore were produced in 2021 — Delhiwallahs, while taking a short break from bursting the deafening sutli bombs and its variants, look up and complain about their amber sky, watery eyes and itching throats. Data from the Central Pollution Control Board stated that the PM2.5 concentration was four times higher than the safety level in the Delhi-NCR region during the festive season, with fire-crackers and farm-fires combining to split ears and clog noses. Meanwhile, the air quality index in the former capital, Calcutta, turned from ‘poor’ to ‘very poor’ for the first time this season. The rest of India, too, is gasping for breath. This despite a ban by the Supreme Court on crackers that are injurious to public health along with restrictive measures announced by a number of state governments.

Given that 2.5 million Indians perish annually on account of toxic air, the discourse on firecrackers and air and sound pollution has, understandably, remained focused on the now as opposed to the then. Yet, even a cursory examination of the history of firecrackers in India can offer fascinating insights into the genesis of civic transgression, institutional complicity and — this is important— possible deterrents.

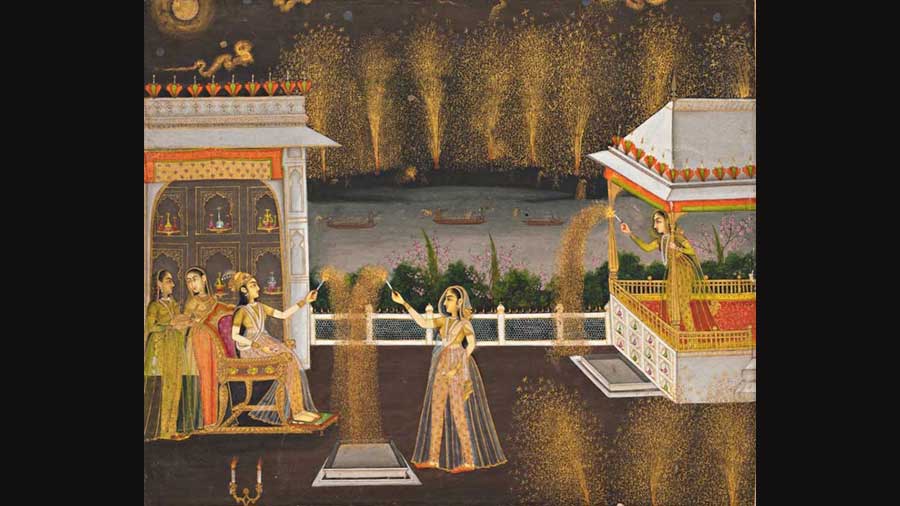

In his book, History of Fireworks in India between 1400 and 1900, the historian, P.K. Gode, cited ancient texts, including the 16th-century Kautukacintamani, to argue that the arrival of the formula of Chinese firecrackers through Arab traders, its subsequent indigenization, along with the discovery and use of gunpowder in Indian military techniques led to the popularization of fireworks in medieval India. The accounts left behind by Duarte Barbosa, a Portuguese traveller, of a Gujarati wedding being lit up, quite literally, by purana pyrotechnics, Gode writes, bears evidence of firecrackers’ presence as a form of public spectacle. The collective enchantment with the sutli bomb’s ancestors became well-entrenched in Mughal India. Dara Shikoh’s wedding, Ira Mukhoty writes, featured an impressive display of fireworks; Satish Chandra, too, notes that a princely sum of Rs 80,000 had been spent on aatishbaazi alone during the wedding of the daughter of a courtier in the court of the Sultan of Bijapur.

What is of particular interest is the symbiotic relationship shared by crackers and mythology. The cultural assimilation of crackers led to a bit of revisionism in mythology. Narendra Modi would be pleased to learn that “Rukmini Swayamvara”, a 16th-century Marathi poem, had ended up spotting phuljhuris and rockets the evening Krishna wed Rukmini. At the turn of the eighteenth century, as gunpowder began to lose its edge in the nascent military-industrial complex, it was the turn of mythology to rescue the firecracker enterprise: a number of illustrated publications began to appear around this time, drawing a — tenuous? — link between Diwali and dodomas.

The trappings of modernity — not myth — have been instrumental in the proliferation of Kalipotka and Co. Import restrictions, complemented by assured supplies from a burgeoning domestic industry — the first firecracker factory had been set up in (where else but?) Calcutta — cheaper prices and increasing purchasing power of the middle class had helped firecracker manufacturers to pocket, till recently, an annual turnover of over Rs 4,800 crore.

This profit is causing exponential losses in terms of the health of the people and the environment, necessitating an attempt at civic redemption. And this is where the past can be of assistance to the present.

The history of firecrackers reveals that the democratization of these products — the regal monopoly has given way to mass ownership — must be reversed. Hungary, Australia, Indonesia, Hong Kong and some other countries have chosen to put firecrackers beyond the reach of the people by imposing stringent bans. This measure is difficult to replicate in India, not only because of lax regulatory agencies but also because the firecrackers industry — the Supreme Court has taken cognizance of this fact — employs, according to the Confederation of All India Traders, lakhs of people in diverse capacities. Therefore, one way of silencing crackers in this country would be taxes. The GST on firecrackers, brought down to 18 per cent from 28 per cent, needs to be raised again. However, the rise must be accompanied by greater sops — lower taxes, bigger markets, competitive pricing and so on — for green crackers. Developed by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research-National Environmental Engineering Research Institute, green crackers, which reportedly release 30 per cent less particulates into the air and are relatively subdued in terms of sound, could be bracketed in a lower tier in the GST hierarchy. There is also a case for introducing incentives for manufacturers willing to explore greener pastures: for instance, the Morani clan, which considers itself to be India’s First Family in firecrackers, has now shifted to the niche market of technology-enabled razzmatazz featuring laser beams, music and illumination. Imponderables remain for those with shallower pockets. Not every manufacturer in Sivakasi, the nation’s metaphorical powder keg, has managed to learn the trick to switch over to making green crackers —this demands a robust interface between the CSIR-NEERI and producers. The approval for licences as well as the examination of the final products, manufacturers allege, is a time-consuming process. Then, there are the noisy protectors of ‘Hinduism’: this year, a prominent BJP leader described the restrictions on firecrackers in Delhi as yet another instance of the bulldozing of Hinduism.

Cretins and crackers go back a long way. What is inspiring though is that women, as usual, seem to have found a way of breaking the spell cast by firecrackers. In Madhya Pradesh’s Chhindwara district, women, supported by a collective of farmers, writers and social workers, came up with replicas of firecrackers that are recyclable.

In so doing, they lit a diya whose flame must not be extinguished.

uddalak.mukherjee@abp.in