This year, there will be no Indian Premier League for the first time since the tournament started in 2008. IPL fans who feel deprived should spare a thought for their English counterparts who will have no live cricket to watch or follow for the first time since 1946.

Ever since the end of the Second World War, the County Championship has been held every year during the English summer. So have Test matches against sides representing other countries. In 1970, the South African cricketers were due to tour; this was to be an all-white side in keeping with the racist policies of the apartheid regime. However, a movement was growing for the boycott of sporting ties with South Africa. In the winter of 1968-69, a scheduled England tour was cancelled when South Africa refused to accept the inclusion of a coloured cricketer, Basil D’Oliveira, originally born in Cape Town but now a British citizen.

The next winter, an all-white South African rugby side toured England. The left-wing weekly, New Statesman, called for a boycott of the matches in an article headlined “Apartheid is Not a Game”. The conservative weekly, The Spectator, answered by arguing that sport and politics must not be mixed. The tour went ahead, but everywhere the Springboks had to face protests; in one case even having to experience the hijacking of their team bus.

In 1970, the institution that ruled English cricket, the Marylebone Cricket Club, was conservative to the core. Thus, as Martin Williamson remarks in an excellent short history of the controversy, “the [English] cricket establishment remained steadfast in its determination [that] the tour [by the South African team] should go ahead. The minutes of several meetings of the MCC and ICC show they were far more concerned with the impending metrication in the UK and how to cope with the change of pitch length from 22 yards to 20.12 metres and the weight of the ball weight from five and a half ounces to 155.8 grammes.” (See: https://www.espncricinfo.com/story/_/id/22252177/politics-killed-tour)

On the other side, anti-apartheid activists such as the South African expatriate, Peter Hain, were determined to stop the tour. They were supported by the great cricket writer and broadcaster, John Arlott, a lifelong opponent of apartheid (and also the man who originally got D’Oliveira to come to England). Arlott said he would refuse to commentate on the matches. Other journalists supported him. The Establishment disregarded them; announcing on May 20, 1970 that the first Test would be played as scheduled in early June.

Three days later, the tour was called off. What caused the bosses of English cricket to capitulate so swiftly? The Labour Party was in power in England; and large sections of their membership were opposed to apartheid. The home secretary, James Callaghan, wrote a tough letter to the Cricket Council, demanding that the tour be cancelled. Reluctant to offend the government, they agreed. Had the Conservatives been in power instead, the tour might yet have gone ahead, with what consequences we cannot say.

The County Championship of 1970 would go on as usual. How would the hole left by there being no Test matches be filled? In an inspired move, a Rest of the World team was assembled to play five matches against England. The brewery company, Guinness, agreed to sponsor the series to the tune of 20,000 pounds, a not inconsiderable sum at the time.

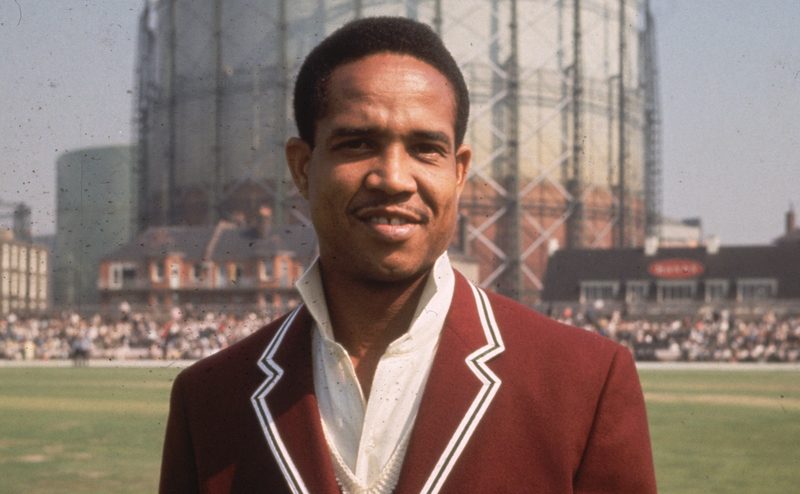

So exactly 50 years ago this month, a multi-racial Rest of the World side was selected to play five Tests against England. The greatest cricketer of all time, Garfield Sobers, was nominated captain. Also selected were four other West Indians, Rohan Kanhai, Clive Lloyd, Lance Gibbs and Deryck Murray; the white South Africans, Barry Richards, Graeme Pollock, Eddie Barlow, Peter Pollock and Mike Procter; the Pakistanis, Intikhab Alam and Mushtaq Mohammad; the Australian, Graham McKenzie; and our own Farokh Engineer.

The home side, England, could not match their opponents in talent, but they had some fine players nonetheless. The captain, Ray Illingworth, had vast experience and a shrewd tactical brain. The batsmen included Geoff Boycott and Colin Cowdrey, the bowlers, John Snow and Derek Underwood. The England wicket-keeper, Alan Knott, was the best in the world.

The first Test began at Lord’s on the 17th of June 1970; the last Test concluded at The Oval two months later. England won the second Test, played at Nottingham; the Rest of the World won the other four. The cricketing public were treated to some glorious batting by the visitors, with Sobers, Lloyd and Barlow scoring two centuries apiece. Barlow also bowled well; as did his compatriot, Mike Procter.

When South Africa toured England in 1965, the left-handed batsman, Graeme Pollock, had made a considerable impression. Much was expected of him this summer too. He fared moderately in the first four matches, but made up with a gorgeous hundred at The Oval, stroking the ball with sublime ease. During this innings, Pollock batted for long stretches with Garry Sobers, the duo adding more than 150 runs in quick time.

Snatches of this innings by Graeme Pollock are up on YouTube. One wishes, reading what was written at the time, that the entire partnership was there for us to see. Thus John Arlott wrote in The Guardian: “The two finest left-handed stroke makers in the World came out together to occupy and determinate the last session. At first Sobers, although he was an hour behind, matched Pollock stroke for stroke; the comparison of cover drives and square cuts was superb entertainment. Soon, however, his captain’s sense perceived the need to set Pollock free, so, playing with easy poise, occasionally rolling out a stroke to remind [us] of his stature, he was generally content to give Pollock the bowling.”

And this is what John Woodcock said in The Times: “For some years cricketers have discussed which is the finer batsman of the two. Well, here they were at the wicket together in a Test match, and in golden sunshine and against an England attack that were fancying their chances... Sobers, who had begun the evening period by matching drive for drive was content, after a while, to watch Pollock at work. Rather than being an abdication of his throne, this was a sign of his greatness. Yesterday Pollock was first among equals. Earlier in this present series Sobers had been second to none.”

Arlott certainly, and Woodcock probably, knew that what they were watching was of great social as well as sporting significance. Pollock and Sobers together at the crease was not just an aesthetic treat; it was a glimpse of a better and more just world. Never before had a white South African and a black West Indian played on the same side in an international sporting contest. That Sobers had as many as five white South Africans playing so contentedly under his captaincy was a decisive repudiation of the theory and the practice of apartheid. It was also noteworthy that on the England side, two South Africans now domiciled in England, the white Tony Greig and the coloured Basil D’Oliveira, were playing together, something altogether inconceivable in their native land.

In August 1970, I was twelve years old, and already cricket-mad. I followed these matches on Test Match Special, and read about them in the newspapers. When I began to write this article, and before I consulted some primary sources, what I remembered best was that in one match — I wasn’t sure which one — Garry Sobers and Graeme Pollock had come together in a riveting partnership. I must have heard parts of the partnership on the radio, or read about in The Cricketer magazine (to which an indulgent father had bought me a subscription). At any rate, that jugalbandi between white and black is what made the most powerful impression on this schoolboy in faraway India. It is nice to think that it might have made a similar impression on some South African boys who were themselves white or black or coloured.

Those five matches between the Rest of the World and England were originally regarded as official Tests, the appellation being later withdrawn by the International Cricket Council. No matter; even if they no longer can be counted in the career statistics of those who played, nothing, I repeat nothing, can take away the historic importance of those matches played in England fifty summers ago. Cricket is rarely anything other than a branch of entertainment; but in those months it became something more, a glimpse of a future South Africa, where the colour of one’s skin would no longer determine social privilege.

The battle against apartheid was fought (and won) mostly in the domain of politics. But sport did play a role, even if it were a modest one. Garry Sobers is not normally regarded as a campaigner against apartheid or, indeed, as any sort of political person at all. In the summer of 1970, he was. And so were all those who played with and against him.