‘Our country is named after the river Sindhu. The Greeks and later the Romans called it Indus.’ This is how a class on our geography would begin. And end.

In effect, that is, for it would have put every listener to sleep. Yet not many rivers in the world have so much to say, with so much unsaid and so little understood. Not many rivers have it in them to, actually, awaken a whole people to their identity.

But this column is not on the river that links three nations — China where in its Tibet region it takes birth, India in the Ladakh region of which it flows briefly, and Pakistan where it runs for most of its long course between Punjab and Sindh before crashing into the Arabian Sea near Karachi.

It is about the people who bear its name, hold its story in their veins.

And who are these people, the Sindhi?

‘Sindhu’ in Sanskrit became ‘Hindu’ in Persian through the Iranian switch of sound from s > h and it is through that Persian lever that Hindus have got their community’s name. Ask any non-Sindhi to think of a Sindhi name and he would think of different ‘...ani-s’. But not every ‘...ani’ is Sindhi. Nor does every Sindhi’s name end with those three letters.

Ambani and Adani are Gujarati, not Sindhi names. And non-‘ani’ Sindhis include two famous ones — J.B. Mangharam of biscuits fame and the Hindujas. So Sindhi name-endings rhyming felicitously with ‘Hindustani’ constitute the rule that proves the exception. They show that assumptions and typifications perpetuate ignorance and entrench misconceptions. Two major ones need to be brought on board straightaway.

First, in India, when we say ‘Sindhi’, we are thinking of Sindhi Hindus. That is not wrong, it is only natural, only right. But when we do that, we slide over the fact that of the nearly 70 million Sindhis in the world, by which I mean those belonging to or descended from persons hailing from the province of Sindh now in Pakistan, the majority are Muslim, not Hindu. So the term, ‘Sindhi’, is a river that splits into two, one Muslim and the other Hindu.

A Sindhi I cherish is not typically ‘Sunni Muslim’ and he is not, of course, Hindu. He is Sufi — the 12th/13th century saint and religious poet, Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, who thought and wrote and lived, like his contemporary, Rumi, for all humanity. There cannot be a greater glory than to be remembered generation after generation across at least five countries — Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh — for a great song. People of all ages and creeds hark to “Dama Dam Mast Qalandar” sung rapturously by amazing singers like the immortal Noor Jehan, the power-house of music, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, and the extraordinary Abida Parveen in Pakistan. In India, the great Wadali brothers and Hans Raj Hans and the iconic Runa Laila in Bangladesh have given “Dama Dam” their own signatures.

Unsurprisingly, Qalandar’s shrine in Sehwan, Sindh, which draws hundreds of thousands from across the world on the day of his urs, has not been spared by the diabolisms of our times. It would! For he is non-sectarian, passionately human. The Islamic State carried out a suicide bombing at the shrine in 2017, killing more than 88 devotees but the shrine did not shut down. The very next morning at 3.30 am, its bell pealed, un-intimidated. ‘Sufi’ is derived from ‘suf’, meaning wool. It is about softness, yes, but a softness that bombs do not rend. Qalandar is Sindhi. Qalandar is Sindh.

The second assumption about Sindhis that needs correcting pertains to their occupation. Think of ‘Sindhi’ and the first image that comes to mind is of a man of few words holding a metal measuring rod that can slide over fabrics and then with a pair of strong scissors snip the yardage you want in fractions of seconds. True, the Sindhi businessman is a typical representative of that community. But so strong is his ‘hold’ on the non-Sindhi imagination of the Sindhi that it obscures the amazing accomplishments of Sindhis outside of commerce. Lal Krishna Advani is the most famous Sindhi in India today outside the world of commerce but Pankaj Advani, who holds the 23-time world record in billiards and snooker wields the cue stick with no less elan than the cloth-shop owner holds the yard-measuring rod, is another. Sunil Khilnani, the acclaimed political scientist and historian who has changed the narrative on our political culture by his book, The Idea of India, is so hugely esteemed as an intellectual and academic that one has to strain to ‘place’ him geopolitically — in the disembodied Sindh of India. Ram Advani who started and ran for over 70 years a much-valued niche bookstore in Lucknow and his son, Rukun, who has established the celebrated publishing house, Permanent Black, are in business but the business of books and of books alone — a most singular achievement.

The pre-eminent Sindhi of our times in India is a political Titan — Acharya J.B. Kripalani (1888-1982). Born in Hyderabad, Sind-Pakistan, and dying in Ahmedabad, Gujarat-India, Gandhi’s earliest political associate in India, gutsy fighter for freedom and president of the Congress at the time of Independence and fiercely independent opponent of the Congress later, was once complimented: “Dada, what a strong constitution you have !” “What constitution,” the nonagenarian replied wryly, “only amendments...” Behind the typical Kripalani quip, somewhere in mind, doubtless, lay the fact that though India’s Constitution cannot now have Sind in its First Schedule that lists our states, the language — Sindhi — has been placed in the Eighth Schedule that lists the languages of India through an amendment — the Constitution (Twenty-first Amendment) Act of 1967.

On the Pakistan side, an esteemed Sindhi is the Magsaysay Award-winning Syed Adibul Hasan Rizvi, renal transplant surgeon and founder of the Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation, with branches (satellite centres) spreading from Kathore near Karachi to ones in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir.

The most important child of ‘Sindh’ for all time, however, is a girl.

Who is she, what is her name? Nobody knows quite exactly. Where was she born? And her religion?

Nothing, alas, fetches up for her. Does that not make her presence here problematic, her residing here tenuous? It does. She has a number though, given to her in her home — India’s most prestigious and one of the world’s most prized museums, the National Museum. A bronze statuette of dimensions 10.5 x 5 x 2.5 cms, she is described as the Dancing Girl of Mohenjodaro. Discovered by the British archaeologist, Ernest Mackay, in Mohenjo-daro, Sind, in 1926, she is a nearly 5,000 year old ‘girl’, an archaeological foundling from what is now the Sindh Province of Pakistan.

The child of that alluvium which the Indus fertilized, of the loam which bears the name of the river, Sindhu, she is, indeed, the very soul of the river that has given her name to our land — India, Hind, Hindustan. She is a metaphor.

Sindh, for that matter, is a metaphor in itself.

A province in Pakistan, it is a presence in India.

It is people, it is jana. A jana without a territory, a people without land. Being Sindhi, in India, is not about belonging to a state but about a state of belonging, of relating. It is about a state of being that does not depend on the physicality of origins or the verifiability of domicile. It is about having been descended from one of the greatest civilizations humanity has known, the Indus Valley Civilization cradled in the basin of that river.

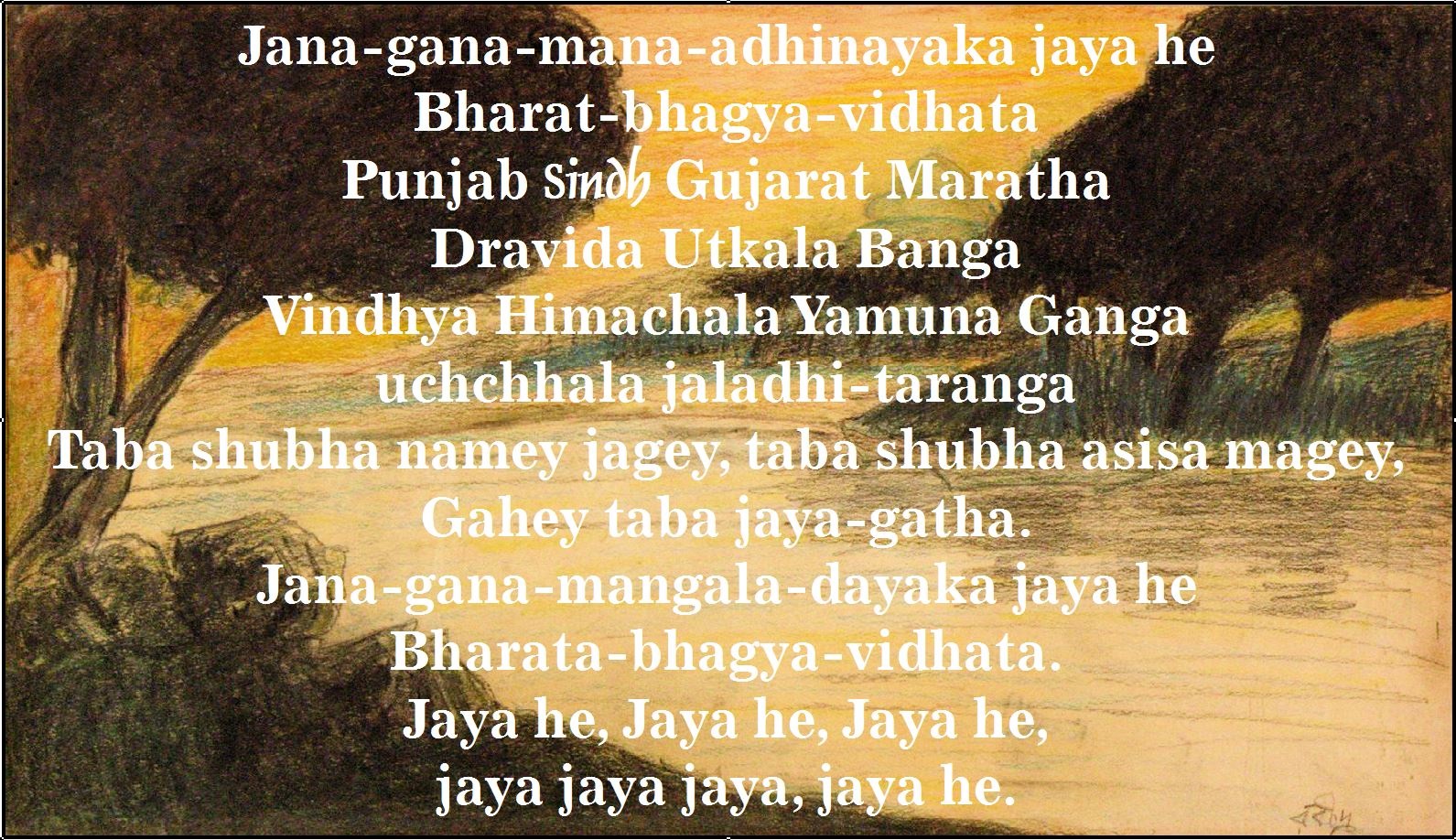

Rabindranath Tagore’s great song from which has emerged our amazing national anthem lists regions, including the territory called Sindh. Literalists have asked how India’s national anthem can include in its regions Sindh, no longer in India. Maps have to be literal, not minds. The Sindh in our anthem, post-Partition, is not a province but a personality. The Sindhu is not a river in India but a pulse of being. And the Sindhi is not just the man or woman whose name ends with ‘...ani’ but each and every Hindustani.