Students of history delve into the works of numerous historians, each belonging to a different school of thought. Predictably, their interpretations vary significantly, reflecting a wide range of perspectives. Upon closer analysis, it becomes apparent that these divergent interpretations are rooted in a certain social, political and economic context: one must not attribute these diverse interpretations to intellectual faculty alone.

An enquiry into the complexities of a historian’s relationship with society needs to first address the relationship of that individual with society. As John Donne wrote, “No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.”

The world sets its course upon all, including historians, moulding us into social beings. Much to the chagrin of the individualists, many theorists now rightfully argue that almost everything is a social construct. The historian, therefore, is also a human being. And as practitioners of the craft of history, their selection of facts and subsequent interpretations are, therefore, deeply influenced by the prevailing societal notions.

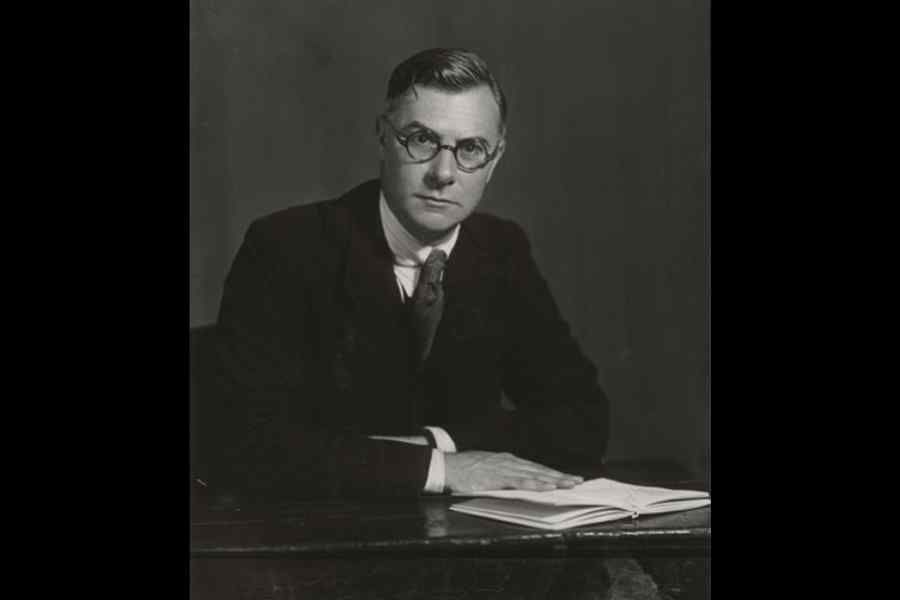

When we start to examine a historian’s relationship with society, we are, essentially, trying to grasp the vantage point from which the historian is writing. As E.H. Carr argues, this standpoint itself is rooted in a social and historical background. This enquiry is seminal to fully appreciating the work of a historian.

In the first chapter of his brilliant book, What is History, Carr ruminates on how a historian deploys certain facts while disregarding others. In so doing, he assigns equal importance to facts and their subsequent interpretations, for facts and documents do not constitute history by themselves: “The facts speak only when the historian calls on them: it is he who decides to which facts to give the floor, and in what order or context.” It can thus be safely argued that to avert the risk of devolving into a mere exercise of “scissors and paste history”, any historical work must assign importance to interpretation. A historian has a plethora of facts at his disposal: he possesses the prerogative to use whatever he likes. Essentially, therefore, history is interpretation.

As interpretation plays a very central role in the writing of history, it is important to underscore that the interpretation of history is influenced by a host of factors: historical method, academic training, personal background and, among other things, political and ideological proclivities. It is primarily for this reason that Carr insists on studying the historian before studying the history written by him. Furthermore, he argues that merely looking for the name of the author on a historical work would not suffice; one should also look for the date of publication, for that, too, could be revealing. What Carr intends to insinuate is that a historian could author two different types of historical works in two different periods.

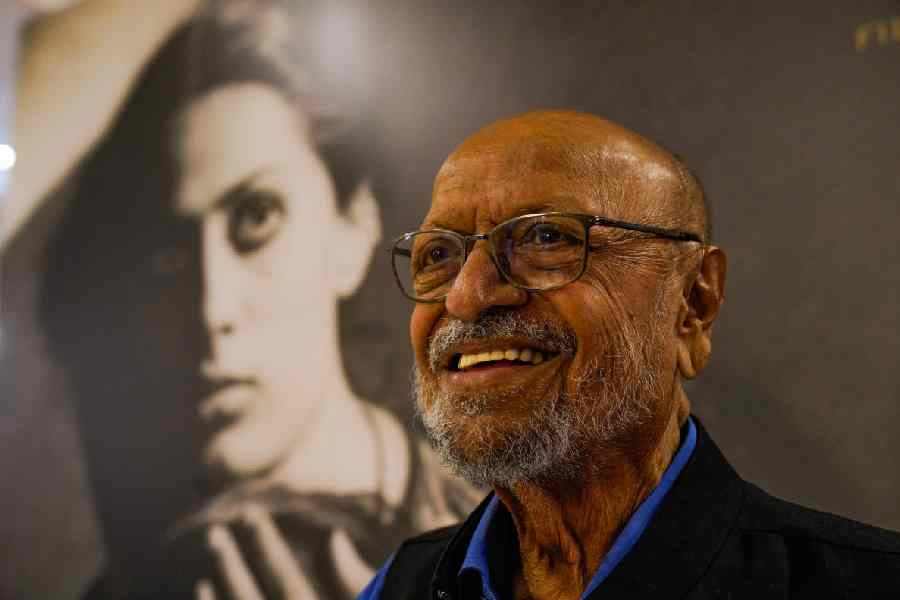

In expounding upon this concept, we could look at the works produced by the very eminent writer, Shashi Tharoor. Although he is not a historian in any sense of the term acceptable to academicians, a cursory glance at his writings reveals a very interesting pattern: before the burgeoning of the Hindutva movement, he had felt no real urgency to author books on Hinduism. It was only after the ideology of Hindutva started to resonate amongst the masses that he wrote two books glorifying Hinduism. Tharoor has famously drawn a schism of sorts between Hinduism and Hindutva; his books on Hinduism allow him to buttress this point as well as project himself as a Hindu leader to an electorate that is predominantly Hindu. Indeed, as Carr argues, “there is no more significant pointer to the character of a society than the kind of history it writes or fails to write.”

Post-2014, we have witnessed a proliferation of historical works informed by Hindutva sensibilities. These works are highly critical of the history written by professional historians. They ostensibly seek to correct the alleged anti-Hindu bias in history. Analysing the motivation behind this crass ideological propaganda masquerading as history requires one to take into consideration the socio-political reality of the country. The way a historian thinks is shaped by the environment he inhabits. Denying this obvious truth constitutes a preposterous fallacy.

In the preface to his book, The Practice of History in India, Anirudh Deshpande makes an illuminating point. He argues, quite provocatively, that every work of history has a definite objective, and, more often than not, the objective is political. “The process of knowing history,” he argues, “begins with an ontology of the self.” The curiosity with which we approach the past is located in a certain social and political context. A student of history should, therefore, pay attention to this context. The way a privileged social group approaches history is significantly different from the way underprivileged groups do. Therefore, a history exploring the nuances of gender, caste and class identities is essential, for it leads to the interrogation of the identities that people sometimes — oftentimes — assume unconsciously.

However, this exploration of the relationship between a historian and his society does not entail that the possibility of writing a history untainted by the environment and pressure of contemporary times is essentially precluded. Many scholarly works continue to be produced even in this heyday of Hindutva historiography. A historian can produce a work that transcends the fetters of his times; but such an exercise requires him to acknowledge these fetters in the first place. Here, again, the counsel of Carr is indispensable: “Man’s capacity to rise above his social and historical situation seems to be conditioned by the sensitivity with which he recognizes the extent of his involvement in it.”

We can argue that the writing of history is a communal endeavour where individuals are engaged as social entities. As the seeker of historical information is located in the present, and his present is located in a social context, history will make sense only when it is studied in light of the socio-political realities of the present.

Shashi Singh studies in Delhi University