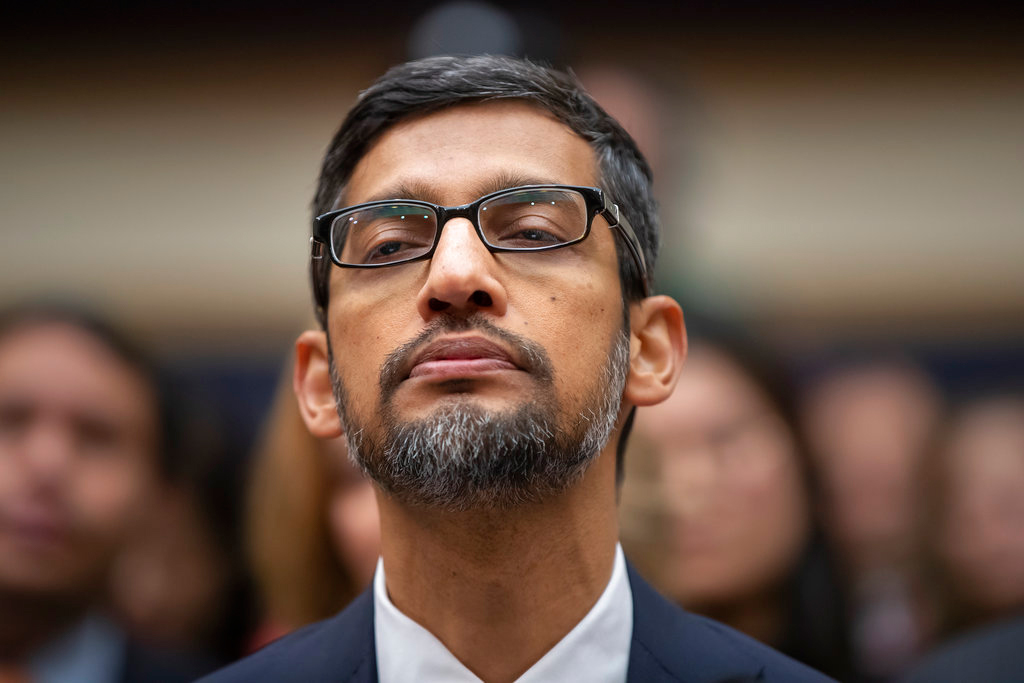

Freedom is not quite ‘free’. The power of digital platforms — also labelled ‘technological giants’ — has brought this irony home. Whether it is the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission seeking to evolve a regulatory authority to monitor how Google and Facebook rank content and protect users’ privacy, or the House judiciary committee in the United States of America questioning Google’s chief executive officer, Sundar Pichai, about users’ data protection, misinformation, political bias and so on, the basic issue, as a senator said, is: are American technology companies serving as instruments of freedom or instruments of control?

Neither alternative is simple. Digital platforms do offer hitherto unimagined freedoms, shored up with a dazzling array of choices; even conventional media platforms need them to interest young people in news they would not bother with otherwise. But the price of ‘free’ digital platforms is high. It affects both businesses and individuals, which the ACCC finds worrying. The technology companies under fire are charged with a lack of transparency in the use of algorithms, resulting in their preferred ‘ranking’ of information and advertisements. This allegedly gives them control over the monetization of information with regard to other businesses and media sites, especially if there is any substance in the allegation that users may be directed to other products of the same company. The system simultaneously allows insidious control over users’ choices, by making predominantly visible those sites suggested by working on user data. Targeted advertisements are just the most obvious manifestation of this.

But would transparency in the use of algorithms breach the companies’ freedom of doing business? The question of freedom is now deeply complicated. Media sites have protested that they work under heavy regulation while digital platforms have none; a balance must be reached for the sake of justice. Breaches of privacy with regard to user data reached scandalous proportions earlier — neither Mark Zuckerberg nor Mr Pichai has come up with convincing solutions to this. Their businesses depend on user data: can such platforms resist means of controlling choices — or minds? Meanwhile, can the fear that political profiling may lead to the control of electoral outcomes be called excessive?

It seems astonishing that even after outrage over the exposure of Facebook’s breach of privacy of 50 million users’ data, it has filed for a patent for an application that will predict the location of its users even when they are offline. The company’s attitude as well as the potential of faceless digital control over private lives is immeasurably sinister. In this context, the political hypocrisy of the Bharatiya Janata Party championing Netflix’s freedom of expression for airing a programme critical of Rajiv Gandhi sounds pitifully mean. Freedom — of expression or business strategy — and rights — to privacy and also to uncontrolled choice — have to be understood afresh. These are not answers, as an ACCC spokesman said, that can be found on Google.