The sudden and dramatic collapse of Jet Airways, after teetering on the brink of bankruptcy for almost three months, raises a tough question for India’s airline industry: why is it wallowing in losses when the combined profits of the worldwide airline industry is projected to rise to $35.5 billion in 2019 from $32.3 billion, an increase of 9.9 per cent? A data sheet that the International Air Transport Association put out in December 2018 throws up other disturbing questions for the Indian airline industry: if the revenues of the worldwide industry are growing at 7.7 per cent to $885 billion and the net profits of the airlines in the Asia-Pacific region are projected to grow by 8.3 per cent to $10.4 billion in 2019, why is it that airlines in India are struggling to climb out of the red? And if the passenger load factor of the worldwide industry is estimated at 82.1 per cent — almost all Indian airlines are comfortably above that number — why are Indian carriers struggling so hard to nudge up their profitability ratios?

The truth is that Indian aviation is weighed down by a number of factors — intense competition, inflated jet fuel prices, high operational costs and weak revenues per passenger — because of which airlines are burning up cash faster than they are earning it. Take the example of Jet Airways. In the third quarter ended December 2018, long before it reported the magnitude of the crisis, the airline had reported revenue per available seat kilometre at Rs 4.39 and cost per available seat kilometre at Rs 5.16 which meant that for every kilometre that a seat travelled, it was losing 77 paise. The more it flew its planes, the greater the losses it would suffer. This is the problem at the heart of the Indian airline industry, which has bedevilled its profitability.

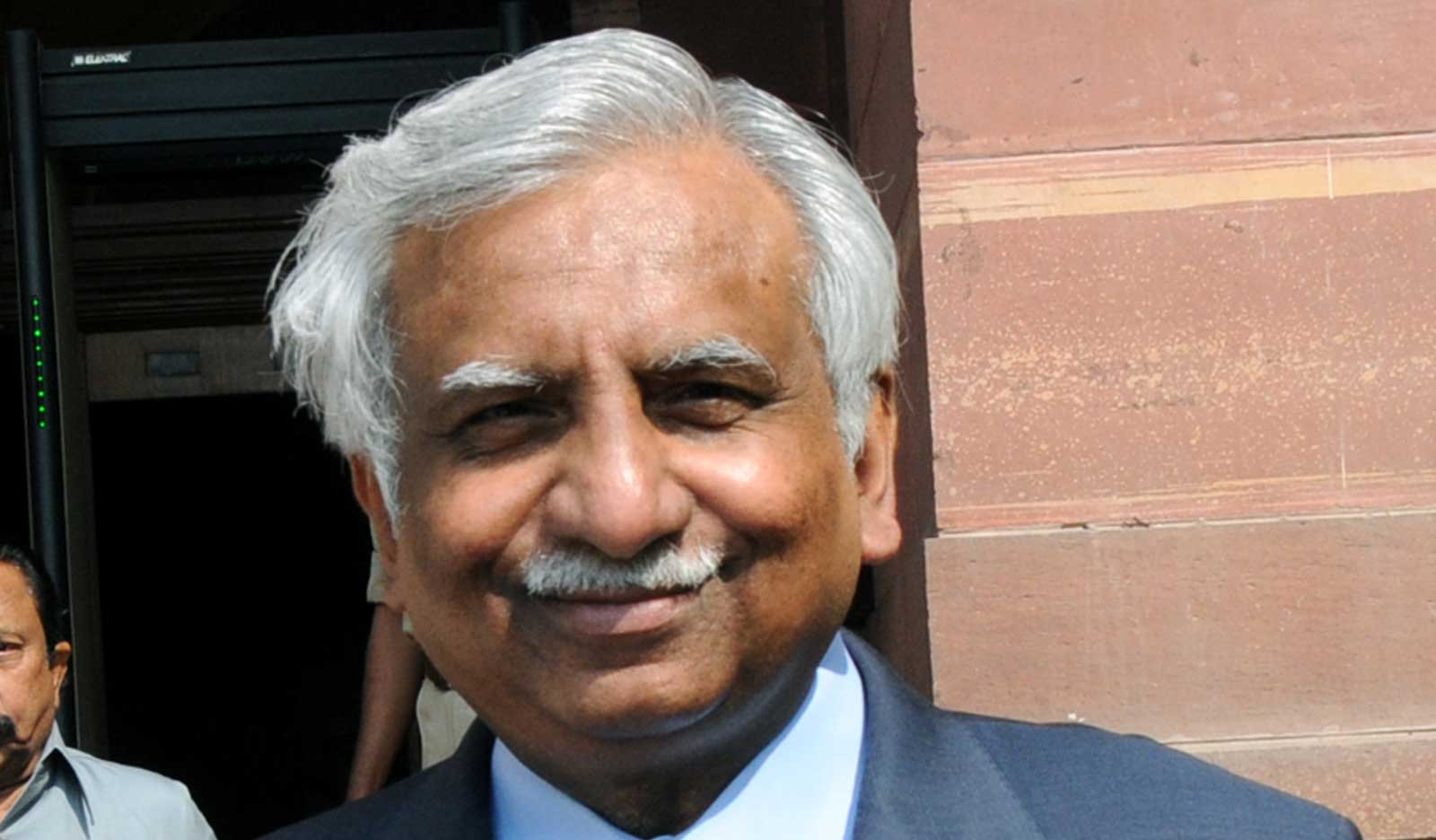

But that tells only part of the story. The Indian aviation industry is one of the most regulated sectors in the country. Its maladies are magnified by the government’s penchant to play favourites. The founder of Jet Airways, Naresh Goyal, was allegedly propped up by a scheming world of crony capitalism. There has been no credible explanation for the banks’ refusal to provide emergency funds after committing to a Jet bailout plan in February. The ministry of civil aviation gave no explanation for shooting down in May last year the plan to merge Jet Airways with it subsidiary, Jet Lite (formerly Sahara Airlines), which would have led to cost synergies and improved cash management. The vultures are now ready to grab Jet’s frequency slots, especially in Delhi and Mumbai airports. There is a deep suspicion that the slot allotment system will be subverted to benefit a few favourites. Mr Goyal played the game for 25 years and benefited hugely. Now someone else is waiting in the wings.