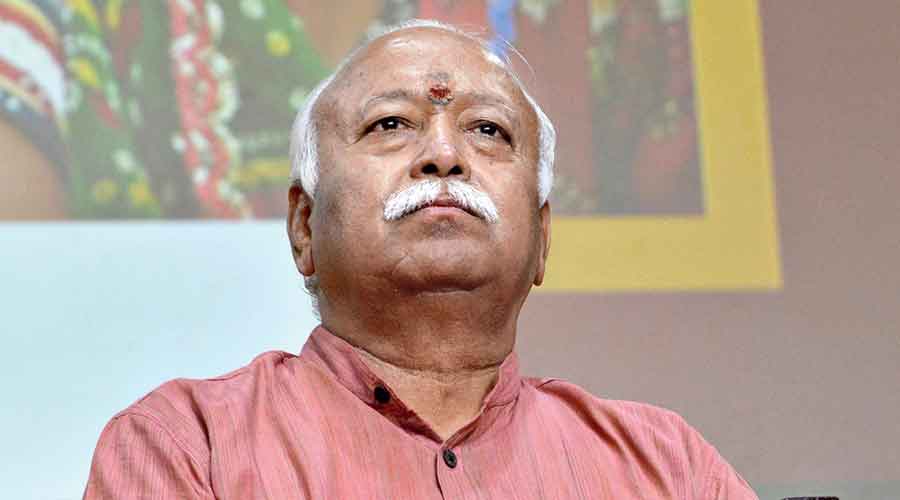

Two news reports appeared recently in a leading national daily. In one, the chief of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, Mohan Bhagwat, waxed eloquent on India’s rich ethos of accommodation and tolerance. In a stunningly secular message, he emphasized that the DNA of all Indians is the same irrespective of religion; that the unifying factor was nationalism; that those who lynch others are working against Hindutva.

The second story was a dissonant and unsentimental contradiction of Bhagwat’s homily. Speaking at a mahapanchayat in Pataudi, Gurgaon, to discuss religious conversion, love jihad and a law to control population, the spokesperson of the Bharatiya Janata Party in Haryana and Karni Sena president, Suraj Pal Amu, called for Muslims to be thrown out of this country and even launched an execrable attack on the Pataudis, accusing them of being standard-bearers of love jihad.

The Indian citizen was thus confronted with two divergent versions of the philosophy of Hindutva on the same day — Bhagwat’s veneer of tolerance contrasted with Amu’s crude but candid outburst against Muslims.

A leading Muslim public intellectual was quick to shower Bhagwat with encomiums for “trying to change the Sangh’s attitude towards Muslims”. He called Bhagwat a beacon of hope for Hindu-Muslim relations for his consistent stance that in our democracy, there can neither be dominance of Hindus nor of Muslims. Yet, one is tempted to ask the obvious question: why then are India’s Muslims living amidst the drumbeats of love jihad, lynching, arbitrary incarceration and hatred? Much has been made of Bhagwat’s unequivocal condemnation of mob lynching. But then, the timing of words is everything. Where were such sanctimonious voices when Mohammed Akhlaque, Hafiz Abdul Khalid, Pehlu Khan and others were being lynched in the name of cow protection? There was only complicit silence.

If Bhagwat was articulating his genuine belief in Hindu-Muslim brotherhood and that Muslims are equal citizens of this country, he can — significantly — be accused of digressing from the fundamental tenets of Hindutva as conceived by V.D. Savarkar, a forceful ideologue of political Hinduism. Savarkar’s conception of the Hindu Rashtra hinged on an implacable, adversarial relationship with Muslims. In 1937, even before the Muslim League resolved to have a separate homeland for India’s Muslims, Savarkar propounded the two-nation theory on the grounds of “centuries of cultural, religious and national antagonism between the Hindus and Muslims... there are two nations in the main — the Hindus and the Muslims — in India”.

Ashis Nandy, the renowned social scientist, ascribed the BJP’s runaway victory in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections to the spread of supremacist, ethnocentric Hindutva through a furtive but relentless RSS machinery that has captured the collective consciousness of the majority community. For those who believe that Bhagwat is leading an ideological transformation — a veritable perestroika — let’s survey what has happened in the last seven years when Bhagwat has been among the most influential voices in the country. Apart from the lynching of Muslims, India has become a Hindutva laboratory that has harnessed anti-conversion laws, the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, and the politics of hate against the minority community.

No change in heart or in thinking in the Hindutva fold is visible but, of late, a change in tactics is discernible. There has been a perceptible climb-down by a regime, which, uncaring of history, past precedent and humanitarian concern, abrogated Article 370, upheld the iniquitous CAA, used draconian laws to quell dissent, curbed the freedom of expression, and encouraged state governments to pass divisive anti-conversion laws. But things have changed dramatically in the last few months. A methodically planned Chinese aggression has already cost us considerable stretches of territory. The criminal mishandling of the pandemic has turned us into a global pariah. International agencies questioning our human rights record and the fetters on freedom of expression has put us on a sticky wicket. The body blow to the regime’s arrogance was delivered by the feisty Mamata Banerjee.

All of a sudden, we have an ingratiating Centre holding talks with the Gupkar Alliance which, not long ago, had been branded ‘anti-national’ by the government. The home minister has written a lead article in a national daily extolling the virtues of democracy. Should Bhagwat’s views on communal harmony then be seen as part of these unconvincing reconciliation efforts?

Mathew John is a former civil servant