“I believe that freedom of thought is a fundamental human right. I don’t want to be a nut and bolt of the state. I want to be a free person. And that is why I resigned.” — Hemantkumar Shah, former principal of H.K. Arts College, Ahmedabad.

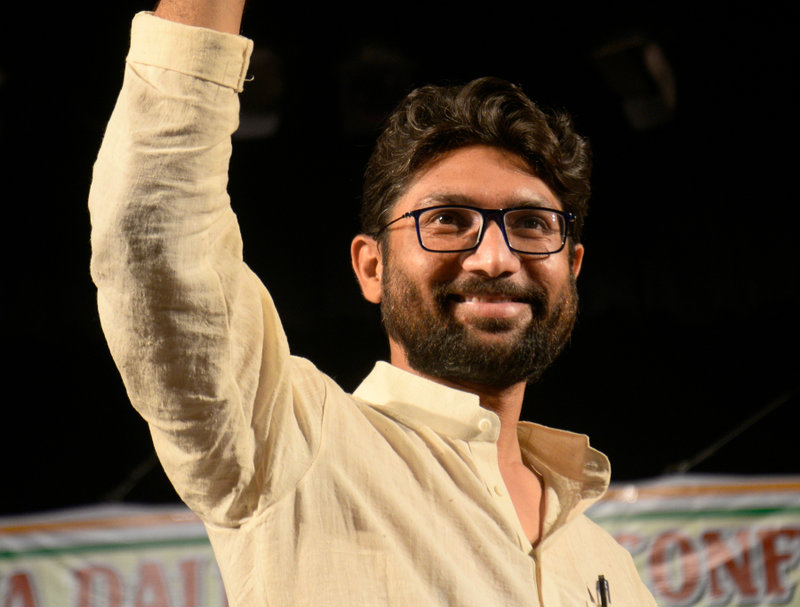

Earlier this week, Jignesh Mevani, an elected member of the Gujarat assembly, was stopped from speaking at the H.K. Arts College in Ahmedabad, where he had himself once studied. He had been invited by the principal, who was forced to rescind the invitation by the college’s trustees, who had been intimidated by Hindutva hooligans. The principal and his vice-principal resigned in protest. I tweeted in praise of their decision, saying that “they represent the best traditions of Gujarat. Patel, Gandhi, and Hansa Mehta would have been proud of them”.

Now Sardar Patel and Mahatma Gandhi are names known to every reader of this column. However, Hansa Mehta is largely forgotten even in Gujarat, so I should say something about her. She was one-half of a great patriotic couple. Her husband, Jivraj Mehta, was a London-trained physician who had often attended on Gandhi, and was himself jailed for long periods during the freedom struggle. Hansa, meanwhile, was active in the All India Women’s Conference, promoting gender equality in society and in politics. Later, as one of the few women members of the Constituent Assembly of India, she was deputed to represent her country at the United Nations. Here, she made a contribution of truly global significance. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was being finalized; on seeing that a draft had the phrase “all men are born free and equal”, she had it changed to “all human beings are born free and equal”.

In 1949, when the Constituent Assembly concluded its deliberations, Hansa Mehta returned to her native Gujarat to become the first vice-chancellor of the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. At this stage, no major American or British university could have contemplated appointing a female vice-chancellor. However, it was barely a year since the Mahatma had died; and his influence and inspiration still animated Gujarat. Besides, Baroda also had progressive Maharajas. In this town and in this state, radical innovations inconceivable in other parts of India (and the world) were possible.

Under Hansa Mehta’s leadership, the M.S. University developed an excellent reputation in the sciences as well as in the humanities. Had university rankings existed in the 1950s, they would have shown the M.S. University on par with the much older universities of Bombay, Calcutta and Madras. Because of who the vice- chancellor was, and what she stood for, the catchment area of this new university was pan-Indian. Painters and sculptors from Kerala and Bengal, and other states, came to teach in what was to become the top-ranked faculty of fine arts in the country. Among the non-Gujaratis whom Hansa Mehta appointed to professorial posts were the country’s leading sociologist, M.N. Srinivas, who was a native of Mysore; and a Tamil couple, C.V. and Rajalakshmi Ramakrishnan, he a biochemist, she a psychologist. The Ramakrishnans had two children; both of whom took their first degrees in Baroda. The girl, Lalita, is now a professor at Cambridge; the boy, Venkatraman (Venki), went on to win a Nobel Prize.

Meanwhile, Hansa Mehta’s work in Baroda was emulated in Ahmedabad, where philanthropists such as the Sarabhais established a cluster of excellent academic institutions; among them the National Institute of Design, the Indian Institute of Management and the Physical Research Laboratory. These, too, had students and faculty from across the country; and sometimes from abroad as well.

When I first visited Gujarat, 40 years ago, it was known as a state where scholars, scientists, writers and artists were given respect (as well as refuge). The legacy of Hansa Mehta and of Vikram Sarabhai was alive. Speaking to professors at the M.S. University, and to students at the NID, one sensed waves of creative energy flowing through them. These institutions were rooted in Gujarat, yet were simultaneously of India, and of the world.

In recent years, however, there has been a conspicuous shrinking of the space for intellectual work in Gujarat. The perception among the state’s elite is that independent-minded scholars make trouble for politics and for business, or, more particularly, for politicians as well as businessmen. A wave of communal and caste riots has inculcated a sense of paranoia and insecurity among the citizenry, which is not conducive to reflective thinking or original research. This philistinism was set in motion before Narendra Modi became chief minister; but it undoubtedly accelerated in the 13 years he was in office in the state.

There was a time when Gujarat was home to world-class scholars of Bengali and Tamil origin; a time when its universities were good enough to educate a future Nobel laureate. Could those days return? That was the question that I faced last year, when I was offered a professorship at a new private university in Gujarat. I accepted the offer, in part because one lives in hope, but in larger part because I am a biographer of the most famous modern Gujarati, and I was attracted to the idea of directing a Gandhi Winter School in a city that the Mahatma had once called home.

In the event, I was unable to take up the job in Gujarat, because powerful politicians in New Delhi made calls to the university’s trustees warning them against me, these followed by threats issued by goons of the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad’s Ahmedabad chapter. I could not live or teach in Gujarat, but I still thought that I could visit the state, to give the odd lecture and meet friends and colleagues. Thus, when a prominent Gandhian institution in Ahmedabad recently invited me to speak on the Mahatma, I accepted immediately.

I was greatly looking forward to my visit to Ahmedabad. I had done much of my research on Gandhi at the Sabarmati Ashram; and I had deep personal connections with the city as well. In the past year, I had spoken on Gandhi in Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Bangalore, Calcutta, Chennai, Kozhikode, Boston, New York, London, and other places; now, finally, I would get to speak on him in the town he had made his own.

The seminar in Ahmedabad was scheduled for Sunday, March 3, 2019. I had chosen to speak on “Mahatma Gandhi as a Communicator”. On the morning of Monday, February 11, I received an email from the organizers “specially requesting” me “to kindly avoid adverse references to the present central government” in my talk. I wrote back at once, assuring them that “I shall restrict myself to Mahatma Gandhi, his life, and his legacy alone, and make no reference to any current politician or Government”.

Then, on Wednesday, February 13, I got a phone call from Ahmedabad, saying the seminar could not be held in what was delicately referred to as “the present climate”. I did not ask for further details, for I did not want to embarrass my already embattled hosts. However, it is likely that the cancellation of my talk was a consequence of what had happened earlier in the week at the H.K. Arts College.

Jignesh Mevani and this writer are of different ages, professions, social backgrounds and ideological affiliations. The one thing we share is that we have been critical of the ‘present central government’. Notably, though, Mevani was due to speak in his alma mater about the life and legacy of B.R. Ambedkar. And I was due to speak in Ahmedabad on the life and legacy of Gandhi. Yet we both saw our respective invitations withdrawn, for the same reason; namely, that even presumably ‘independent’ and ‘autonomous’ institutions in Gujarat are too fearful to invite Indians who have ever said anything critical about the prime minister. Even if we choose to speak about some other subject altogether.

That is why I spontaneously saluted the principal and vice-principal of the H.K. Arts College, for resigning their posts in the cause of freedom of expression. Their act recalled an older and nobler Gujarat, the Gujarat of Patel, Gandhi, and (especially) Hansa Mehta. Indeed, I have no doubt that the open-mindedness that once characterized the state will return one day. Authoritarians and authoritarianism are transient, while the human urge to freedom is permanent. There was a Gujarat before Narendra Modi and Amit Shah acquired their hegemonic hold over the state; once this hold is weakened, that other and freer Gujarat will re-emerge. I look forward to seeing (and speaking in) it.