The Indian Constitution recognized two social groups as especially disadvantaged: the scheduled castes, known in everyday language as Dalits; and the scheduled tribes, commonly known as Adivasis. Both groups are extraordinarily heterogeneous in their composition; divided by language, caste, clan, religion, and forms of livelihood. There is absolutely nothing in common between a Madiga in Andhra Pradesh and a Jatav in Uttar Pradesh, except that both can apply for a government job under the ‘SC’ quota. There is absolutely nothing in common between an Irula in the Nilgiri Hills of Tamil Nadu and a Gond in the Mahadeo Hills of Madhya Pradesh, except that both can apply for a government job under the ‘ST’ quota.

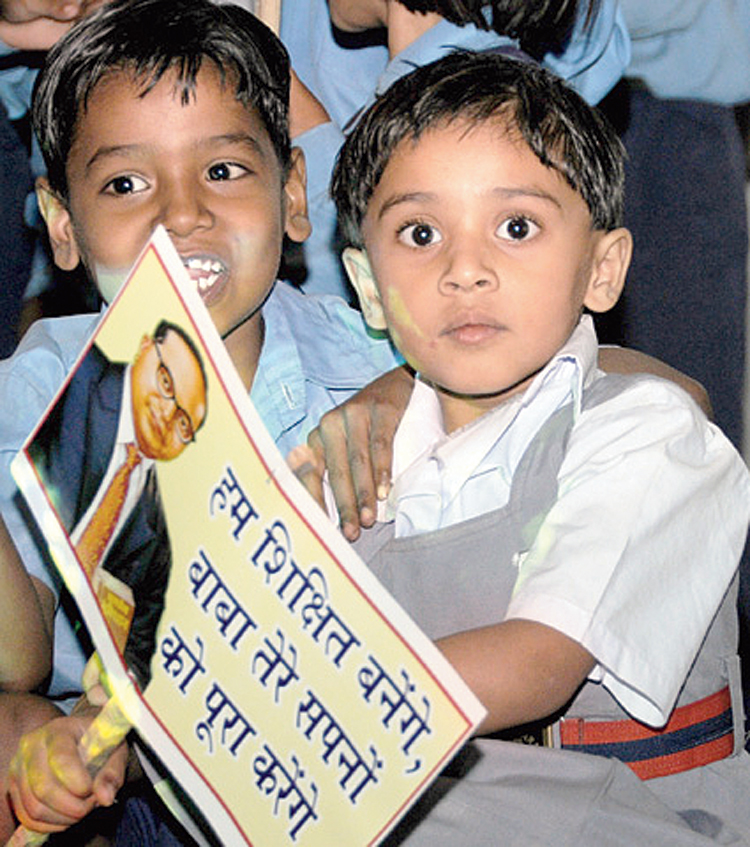

That said, Dalits across India are indeed united in one singular respect; whether in Kerala or Karnataka, Punjab or West Bengal, they have before them the example of the great B.R. Ambedkar. For all his intellectual prowess and the high political office that he held, in his lifetime, Ambedkar had a popular following only among his own sub-caste, the Mahars of Maharashtra. However, after his death, he has become an icon for Dalits all over the country. On the other hand, there is no comparable figure for the Adivasis; no tribal leader, dead or alive, who has the same sort of stature and regard cutting across regional and linguistic differences.

I had long known, and been impressed by, Ambedkar’s exemplary position among Dalits. This was brought home afresh to me by reading the autobiography of Eknath Awad, originally written in Marathi, and wonderfully translated into English by Jerry Pinto. Awad was born a Mang, in the Marathwada region of Maharashtra. However, because of his intense desire to educate himself, manifested when he was very young, his relatives began to refer to him as a Maharcha aulad, Son of a Mahar. For it was Ambedkar, born in a Mahar home, who had memorably said, “Education is the milk of the tigress. Once you have drunk it, you cannot but roar.”

As a high-school student, Eknath Awad closely read Ambedkar; while also avidly following the speeches of the Socialist MP, Nath Pai, a once inspirational but now sadly forgotten figure. Growing up in the 1970s, Awad was inspired by the Dalit Panthers and by the movement to have the Marathwada University named after Ambedkar. Of the latter struggle he writes: “If a morcha supporting the Renaming went out on one day, a morcha against it would follow on the next day. This led to a chain of morchas, one after the other. The Shiv Sena was against the Renaming. Everyone, students, teachers, lawyers, doctors, right down to the villagers, were taking sides.”

The movement for renaming provoked savage retribution from the upper castes. As Awad recalls, “[t]he Mahars were the target of systematic arson... A hundred and eighty villages in Marathwada witnessed such violence. The riots raged for ten days. At eighteen places, there was police firing. More than a thousand Dalit homes were set on fire.” As a college student at the time, Awad was deeply affected by this conflict. “As the news [of violence against Dalits] came in”, he writes, “I would grow restive; my mind would fill with anger... I would come forward to make representations to the government. My mother would worry for me as I was upsetting many people in the village.”

Reflecting on his early struggles against poverty and caste discrimination, Awad says: “Deprivation has no joys at all. If you must swallow insults and disrespect all your life, it does not make for a life of happiness. But when a human being begins to fight the circumstances of life, when she takes up arms against injustice, then life offers another form of exhilaration. In my experience, the struggle itself would create an outlet, a drain for my rage and anger. This became something of a habit with me.”

Of the Maharashtra of the 1970s and 1980s, Awad remarks: “At that time, both the Shiv Sena and the Congress Party had toxic attitudes towards the Dalits... While the Shiv Sena was seen as a Mumbai-based party that was fighting for the rights of Marathi people, in the villages it had the reputation of being an upper-caste party that was upholding the bitter pride of Hindu casteism.”

After getting a BA and then a Master’s degree in Social Work, Eknath Awad began working with an idealistic upper-caste couple, whose socialist beliefs led them to work with Adivasis, then (as now) the most victimized section of Indian society. Based on his own experiences, Awad offers an instructive contrast between Adivasis and Dalits. “The Adivasi can bear much hardship”, he writes, “the Dalits can bear much struggle.” He notes that “in any social movement or revolution, they [the Adivasis] join only as followers of some other group or leader. They have had no leader of their own. Right up to today, there are very few leaders among Adivasis.”

In his travels around Maharashtra, Eknath Awad found repeated confirmation of his childhood experience that his fellow Mangs were far more submissive than Ambedkar’s Mahars. He worked to overcome this; by urging Mangs to leave their traditional occupations behind and seek a modern education instead. His memoir provides vivid accounts of the many struggles that he participated in; some successful, others not so. All through his adult years, he recalls wryly, “I was neck-deep in gheraos, morchas and a regular at police stations and government offices.” He writes that after he led a campaign for justice to victims of caste atrocities, “I had enemies in every village. Death threats followed.”

Eknath Awad’s book is published in English under the title, Strike a Blow to Change the World. It is a work of literary merit as well as of sociological insight. There are tender portraits of his fellow activists, of his family members (particularly his wife), but also sharp analyses of the forces which impede or enable the progress of social justice. Thus he writes: “It is not possible to solve the problem of Untouchability by providing the Dalit with food and building a few cement houses for them. It is much more important to awaken their sense of self-respect.” Or again, of a Mang labour contractor who showed undue haughtiness: “Whatever a person’s caste status, as soon as he gains a little power, even if it is over someone as weak as a sugarcane cutter, he begins to become arrogant.”

When he began his career as an activist, recalls Awad, “because I was born a Mang, the main Dalit parties offered me stepmotherly treatment. It was as if only one caste had the right to use Babasaheb’s name. I did not think it right that we had trapped Babasaheb’s ideas in a caste ghetto.” In the event, Awad himself played a notable part in the wider recognition of Ambedkar’s achievements; in making him a symbol of inspiration for Mangs as well as Mahars, and among many upper caste individuals too.

In the 1970s, when Eknath Awad was growing up, the upper castes of Marathwada were violently opposed to a university being named after Ambedkar. Many years later, Awad started and successfully ran a co-operative society named after Ambedkar’s wife, Ramabai. Women of different castes took part in this co-operative, which helped fisherfolk, cattle-herders and bangle-makers sell their produce at a fair price without any exploitative middlemen. By 2010, some two million families were beneficiaries of this co-operative. With a sense of entirely legitimate pride, Awad writes: “The very villages that had opposed me because I had wanted the Marathwada University renamed for Babasaheb were now all part of a microcredit society named after his wife. What more could I want? In a socially backward district, the upper castes were now celebrating Babasaheb’s birth anniversary. Who would have ever dreamt it? But this is now an annual event.”

B.R. Ambedkar died more than six decades ago. Yet he continues to inspire Dalits across India to educate, organize and agitate; to challenge and overcome the discrimination they may face. Even more remarkably, perhaps, Ambedkar’s name and example command respect among the upper castes; a respect that might sometimes be belated and grudging, but which can no longer be withheld. Long after his death, Ambedkar remains a critical resource whom Dalits can draw upon morally, politically, and intellectually. Tragically, the Adivasis of India have had no such leader to inspire and move them in their own struggles for dignity and self-respect.