There is now an eighth cardinal sin. The price for this most grievous of transgressions has to be paid much before a person can suffer the furies of hell. Studies show that from a marriage to a job, everything can be lost to those who succumb to the temptation of the exclamation mark. This slim, furtive punctuation mark, once it slips in at the end of a sentence, can turn a statement into a shriek or a reprimand, or introduce bewilderment or disbelief where there is none. Given the range of emotions it encompasses, it is no surprise that this mark is the pet peeve of editors across the globe. Conveying emotions in written text is a difficult enough job without adding confusing punctuation marks into the mix. Authors, too, have been known to abhor this punctuation. F. Scott Fitzgerald said that using exclamation marks is like laughing at one’s own jokes. But advice, including the one provided by Fitzgerald, generally falls on deaf ears when it comes to the current president of the novelist’s country; a review of Donald Trump’s tweets would reveal that the president uses more exclamation marks than alphabets.

But the exclamation point is not the only villain of the piece. Punctuating a sentence has come a long way from the use of the punctus — a point used to indicate a short pause or minor break in medieval texts. The idiosyncrasies of the internet — online memory is infinite, yet writing needs to be restricted to 240 characters or less — have ensured that a wide range of symbols have now been appropriated as punctuation marks. For instance, the tilde — originally an accent in Spanish alphabets — is now used to acknowledge the usage of tired clichés in one’s speech or to emphasize the ridiculousness of something. There is also the ingenious sarcmark — its name is self-explanatory — for those who cannot recognize when a compliment is really criticism. At other times, punctuations are combined because one mark simply is not enough to convey what one is feeling. The combination of the question and exclamation points is an example; it denotes surprise or shock but also asks for a reiteration of whatever it is that provided this jolt.

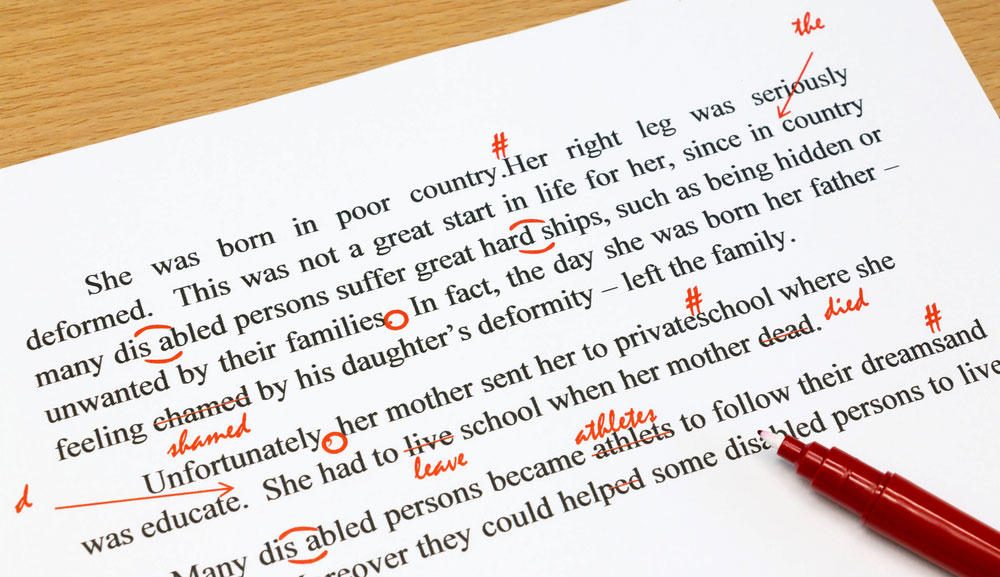

It can thus seem like the English language is being pulled in two separate directions. On the one hand, there are the wild abbreviated inventions of texting, pidgin languages that are born when an ethnic language bangs into English and the technospeak of modernity. On the other, there is the ‘Grammar Nazi’ trying to pull up the drawbridge to shoo away the quirks of modernity, in an attempt to preserve a past reminiscent of Jane Austen heroines speaking with polished wit or Henry James churning out stern sentences. But neither Austen nor James can match the maverick Bard of Avon when it comes to blurring the line between grammar’s playfulness and gravity. A look at Shakespeare’s first folios reveals that colons are smattered all over and are often preferred to full stops; commas cluster together in short bursts; parentheses and dashes wander around looking for a home and, frequently, any attempt at punctuation disappears altogether. Now imagine Juliet saying “O Romeo, Romeo! wherefore art thou Romeo?” without the exclamation mark.