Most things die, but many do not. The mountains are still young, and they were young on the ancient. They were there, youthful props in the playground of the Gods, and they sprung springs and lakes about them, and rivers roaring down, and sprung valleys and dales eddied with flowers. Such valleys and dales that no human hand works, such valleys and dales that are magically kindled by unseen elves. Elves that live on heights no human can approach. Elves that service the schemes of the Gods. Those elves are young too.

And they are floating about, the air’s thick with them, little elves, dead elves but young elves, rising from that hot and poisoned abyss, taken by sweat and aches and fevers, their flesh sucked of vigour, their bones smashed and ground, the light of their eyes squeezed out, the life snuffed out of them to a lightness. Such lightness that it can only begin to float and go far away from grasp. Gone. Forever. Into the floating world. Young things, but no longer man’s things. Young things turned into things of God. Young things dead before their time. Most things die. Some things die before their time. Some things remain forever young — only a million years old, just growing.

Like the mountains, which are there, still young, when the Gods have become myth and lore, or perhaps they are still there, no longer visible. Or no longer wishing to be visible to the menagerie. No longer wanting to be part of this daily drag through the streets, the sound of a barked out cry or a hoot, no longer wanting to be invoked for politics and prejudice. But the Gods should have got used to this. To being used as material for politics and for prejudice. It is one of the ways Gods serve men. As material, and as medium. God, inspire me to fight that other God. God, let me build a house for you. God, let me be savage and slay in the name of that house for you. It may seem we are serving the Gods, but in truth the Gods are serving us. Or our purposes. But purposes too die, and we give birth to new purposes so that we may have cause to live. Such vanity and hope! We will die, all of us; who doesn’t? Of one this or another. And then we go. Some go down, six feet under; some go up, in flames, some lie flat as offering to be consumed. Is there more to it? Who knows? Do we remain after we have died? Who knows? Are we the sum of our body parts and no more? Who knows? The dead go where they go, we shall find out when we are dead.

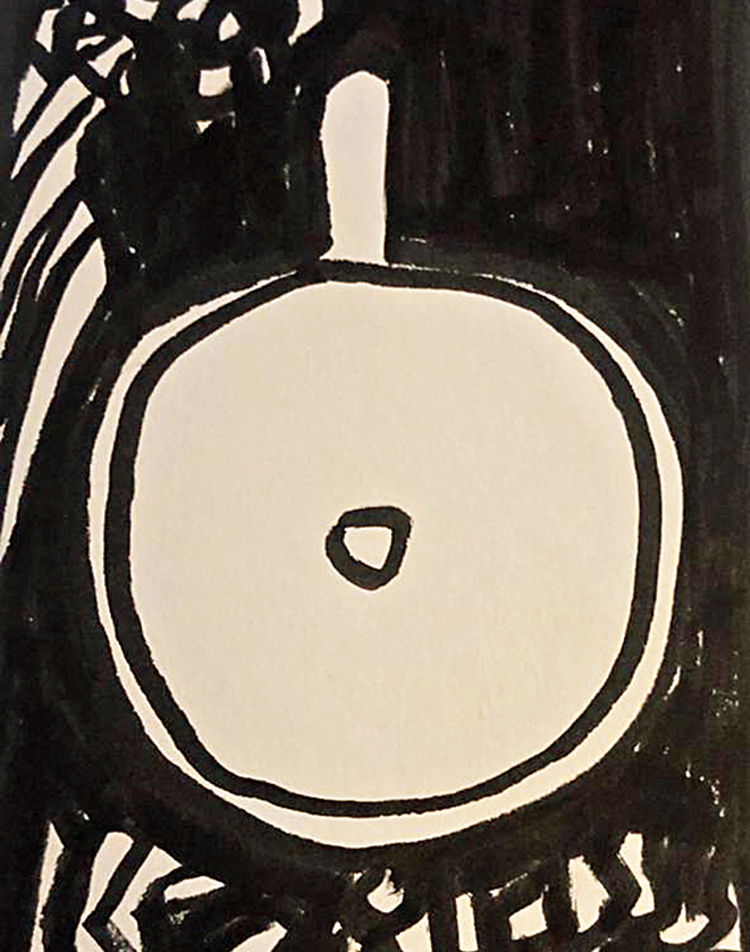

Often we do not even know why the dead died. Most things die, but for this reason or that. Sometimes things die and we can’t tell the reason. We turn to guessing. We turn to Forbidden Fruit. It can kill. Always remember. That is why they say learn from history. Or myth. Same thing, in our time they are synonymous, history and myth — history can be turned into myth at the snap of a finger, myth can be turned into history. But the point is that those that do not learn from history or from myth are condemned to die by it. Or some such thing, don’t expect everything that’s writ here is right. Most things that are writ here aren’t. But be careful of Forbidden Fruit. Never good for health, and often fatal.

The one that the Apple did eat

The original Poisoned Fruit

That sin nothing did beat

And we repeat it to boot.