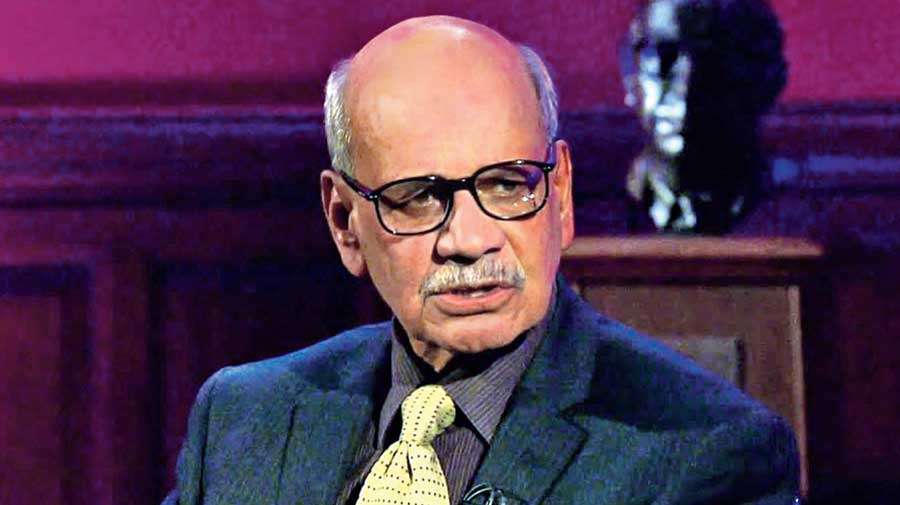

A retired Pakistani general and one-time director-general of its Inter-Services Intelligence has recently written a novel, Honour Among Spies, a thinly-veiled depiction of contemporary Pakistan politics, civil-military tensions, India-Pakistan relations, the war on terror and so on. The author, Asad Durrani, had acquired some notoriety in Pakistan when he co-authored The Spy Chronicles with A.S. Dulat, the former head of India’s external intelligence. This book was a series of conversations between the two on India-Pakistan conflicts and on Kashmir. This public act of intellectual cooperation of a Pakistani general with an Indian spymaster was unusual, as was a frank discussion on Kashmir with an Indian. The fact that the book was published in India muddied waters further in Pakistan and in the resulting dust-up General Asad Durrani was investigated and his pension temporarily stopped (he had retired in the mid-1990s). General Durrani followed up with a second book, Pakistan Adrift — in part autobiographical and covering Pakistan’s political and military history post 1989. His treatment was critical of the army brass, Pakistan’s political class and of the army’s political role in general.

The latest foray is in a different genre — being a novel. Yet, for observers of Pakistan, its central characters are close enough to real-life figures — Indians and Pakistanis, generals and politicians alike. While General Durrani’s opinions and motives have been debated, his books, especially the latest novel, mark him out as a contrarian — although perhaps one who has come to contrarian positions much after he left the army.

We have a more striking example of another dissident general from the 1950s. This was the famous ‘General Tariq’ who was responsible for Pakistan’s failed attempt to nullify the Maharaja of Kashmir’s accession to India decision by capturing Srinagar. ‘Tariq’, named after a famous Islamic military hero credited with the conquest of Spain, was the self-styled name of Akbar Khan, the planner of the strategy of tribal raiders backed by Pakistan army personnel infiltrating the Kashmir Valley in October 1947. The strategy failed but enabled Pakistan to gain a toehold in Mirpur and Muzaffarabad, which it retains. General Akbar Khan’s book, Raiders in Kashmir, was published originally about half a century ago and was clear proof of the planning and high-level government involvement that were behind the raids that led to the first India-Pakistan war.

In the aftermath of the war, Akbar Khan was an embittered and ambitious man blaming the government for not committing fully to the Kashmir struggle. In 1951, he along with many others were accused and tried for mounting a military coup. This was the famous Rawalpindi Conspiracy case, which included, among the conspirators, the poet, Faiz Ahmed Faiz. Their sentences for lengthy prison terms were subsequently reduced or pardons given. Akbar Khan found himself a free man by the mid-50s although he was dismissed from the army. He was back as a minister post 1971 in Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s government. His Raiders in Kashmir is a bitter diatribe against Pakistan’s government and the army chief, General Ayub Khan, and others for their failure to pursue the Kashmir cause with greater vigour. “Ayub Khan”, he wrote, “could give Pakistan the world’s first Field Marshal without even being in the field.” He went on to cite Ayub’s successor thus: “Yahya could top it by giving India the world’s second one!” — referring, no doubt, to General Sam Manekshaw being designated as Field Marshal for his role in the 1971 operations and military victory. Akbar Khan’s fanciful claims about Kashmir and his giant-sized ego earned him a large share of detractors. Ayub Khan was dismissive of him and those of that ilk, attributing rapid promotions in the new Pakistan army as having raised unwarranted expectations and created a number of ‘Unhappy Bonapartes’.

The 1965 war also generated, although much after the event, a few contrarian views. The idea of a glorious victory against a larger army is jealously preserved in Pakistan. In 2002, Lieutenant General Mahmud Ahmed published a detailed history of the 1965 war tellingly entitled Illusion of Victory. This remains possibly the most detailed military history of the 1965 war written in either country. It was, however, never ever distributed or sold in any significant numbers basically because the Pakistan army bought up all its copies to prevent its distribution. The author was also a former DG, ISI and, in fact, held that post when the 9/11 attacks took place in the United States of America. He was to be replaced soon thereafter because of his perceived Islamist leanings and Taliban sympathies. His treatment of 1965 was a realistic, if unwelcome, assessment of Pakistan’s strategic failures: “The greatest casualty of the 1965 War was perhaps our modesty. We prided ourselves over achievements which were doctored for public consumption to boost the national morale. We began to believe what was meant only for the sake of propaganda... The price of undeserved glory was paid barely six years after the 1965 war [when] the bitter harvest of humiliation was reaped in East Pakistan in December 1971.”

Relating the 1965 war — to many a high watermark in Pakistan’s history — with the depths of 1971 was a contrarian perspective and marks the author as a dissentient. Incidentally, he was one of the ‘Kargil clique’ — the generals around Pervez Musharraf when that misadventure was planned and executed. General Mahmud Ahmed went on, post retirement, to become a preacher consolidating his reputation as an Islamist general.

The 1971 war has been a fertile terrain for literary activity especially from Pakistani military officers. Over the years, most of the principal actors have written their accounts. One of the generals who did so wryly noted, “History, it is often said, ‘is written by victors’. In the case of East Pakistan, it has been written by the losers.” On the whole, however, these are not in the nature of dissident views so much as exculpatory.

While there are some others, dissentient narratives from senior military officers in Pakistan have remained relatively rare. This is especially so in the context of the vast literature that the study of the Pakistan army has generated. In large part, this is obviously because the regimen of the military ensures that public articulation of dissidence is rare even long after retirement. Yet, each such contrarian view has generated enormous attention even in the cases when the protagonist is writing a very long time after he had a substantive role as a participant in events. In some significant part, this is because the role of the military in politics in Pakistan and all of its consequences has a timeless quality to it. It is like an endless loop that repeats its crests and troughs. Each high and each low may appear momentarily like a beginning or an end but, in fact, is only one more moment in a rhythmic sequence in some obscure metre. Another well-known military dissentient, Asghar Khan, not a general but an air marshal, gave a title to one of his books that summed it up: We’ve Learnt Nothing From History.

The author is a retired diplomat and is currently Director General of the Indian Council of World Affairs