Sometimes, the major battles of our time get caught in coteries and clubs and float adrift from the democratic imagination. The debate around the Central Vista project is one such event. How does one conceptualize it?

It is, after all, a debate about a building. Perhaps we need to go beyond an architect to a philosopher. Martin Heidegger, the German philosopher, established a relation among building, dwelling and thinking. Buildings, Heidegger argued, transcend materiality. They are forms of living that have to be seen iconically. A building like the Parliament or even an annexe to it speaks history, invokes memory. The Central Vista has to be seen as an unravelling of democracy, as a symbolic celebration of difference, as a metaphor for imaginative debate.

Oddly, when Bimal Patel, the architect, invoked his discussion of the building, all that Narendra Modi talked about was ‘functionalism’. It is strange to have a prime minister who does not know the difference between Parliament and plumbing and, worse, to have a technocrat carrying out his premises unquestioningly. Both seem indifferent to the fact that a public building of that order has not been subject to public discussion. It is as strange as arguing for a future where we see a Parliament behave indifferently to the people. Worse, Patel reduced the debate to a technical answer to a technical question. The Central Vista budget and everything else is presented as a fait accompli. If a building cannot be a dwelling in a representative sense, how can democracy be a way of life and living? This is the real issue that confronts the Central Vista. Modi sees it as if it is another sculpture like the Sardar Patel statue. He has no sense of building as an embodiment of tradition or conversation. All he sees is the monumentality of power.

The word, Lutyens, itself should have signalled the prelude to a different debate. Lutyens represented the imperialism of the city, the Haussmannic grids of centralization that the architect first built as frames to control the crowds after the Paris Commune. Baron Haussmann wanted an architecture of control and centralization, not community and conversation. Modi, for all his use of Lutyens in the folklore of his critique of the Congress, endorses Lutyens in his mentality in a way that no predecessor has. In his heart of hearts, he is not a populist but a hegemonist, desperate for control. The sociologist, Patrick Geddes, a critic of Lutyens, showed that the mechanistic architecture of Lutyens had neither a sense of tradition nor of memory. There is an egotism to architectural power, an indifference to the margins, that Modi-Patel find seductive. This is a Parliament that does not want to listen to the people or to history because it is convinced that it needs to make history tone-deaf to democracy.

Modi and Patel represent two ways of indifference to democracy. Patel follows empty protocols; Modi treats protest as empty irritants. The Modi who raved and ranted as a critic while in the Opposition seems indifferent to criticism. We have to raise a second set of questions here. Modi, who has repeatedly emasculated dissent or imprisoned it, cannot be a mere monograph in urban planning; he has to become part of the folklore of democracy, be subject to popular critique the way Sanjay Gandhi and Jagmohan were during the days of the Emergency. Technocracy can fail scholarship no matter how immaculate but what technocracy can’t fail is democracy. For Modi, Parliament could well be an extension of Madame Tussauds where people are embodied in wax and democracy as memory. A space has to come alive to fight Modi who has embalmed democracy.

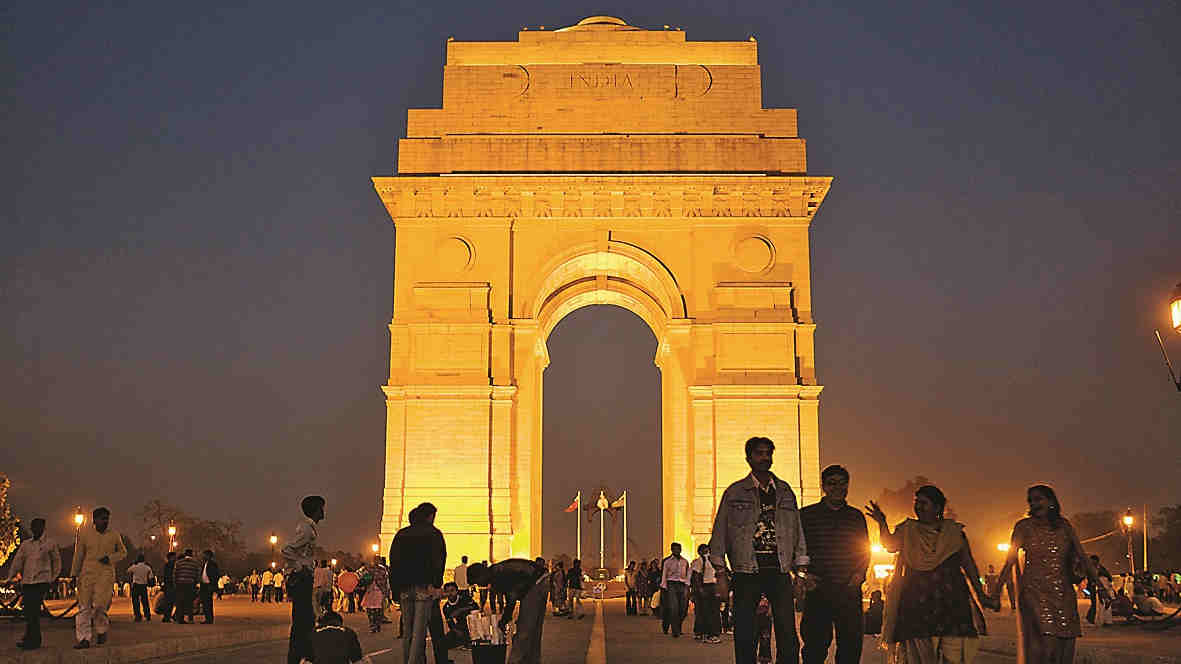

Probably the biggest casualty of the Central Vista debates is memory. I am not talking of memory as history, but as orality, as lived memory embodied in crowds walking public spaces, responding to the symbols of governance. A walk around Janpath was a way of consuming democracy, of sustaining democracy through the orality of storytelling. The Central Vista is more a collection of offices, a secretariat rather than a part of a parliamentary performance. It is as if the public, the crowd, the rhythms of citizenship, the folklore of democracy have no meaning for this regime. The historian, Narayan Gupta, has repeatedly emphasized the power of space and place for memory. One wishes governance absorbed a bit of that wisdom. It is great scholarship and intuitively democratic. Once one forgets that a city is a mnemonic of democratic events, a regime has lost its legitimacy. The Central Vista is a sign of the times. It signals the new Parliament of indifference, shockingly abstract from debate, difference, and people.

Yet, in a deep way, the power of dissenting scholarship reasserts itself and one has to celebrate the dissenting imaginations. This dissent, in fact, now has to be read differently. Critics show that there is unity among Modi’s authoritarianism, his indifference to the margins and to the ideas of dissent and scholarship.

The Central Vista then becomes a variant of authoritarian decision-making. The Gujarat riots had shown how a majority could dismiss the margins. The Citizenship (Amendment) Act displayed the contempt for the refugee as citizen. Lakshadweep demonstrates how development as authoritarianism can dismiss the fate of the tribe as a critical issue. The Central Vista adds to this the sense that Modi wants a monolithic Parliament, a democracy without debate. When dissent lapses into silence and memory, the only obstacle to authoritarianism fades away. Be it minority, refugee, tribe or dissenter, our regime has no place for them.

Shiv Visvanathan is an academic associated with Compost Heap, a network pursuing alternative imaginations