In a piece published in these pages on July 1, 2023 — almost exactly a year ago — I wrote that while I had once harboured large ambitions for the renewal of Indian democracy, for the next general elections I had just one, modest, hope: that “no single party should get a majority of seats in the Lok Sabha; indeed, that the largest single party should fall substantially short of a majority. For while our current prime minister is authoritarian by instinct, this unsalutary aspect of his personality has been given ballast by the two successive majorities his party has won in general elections.”

Whether even this modest hope would be realised looked unlikely in July 2023. Or for several months thereafter. In an article published in Foreign Affairs in February 2024, that was sharply critical of the prime minister’s policies, I had nonetheless remarked that “INDIA will struggle to unseat Modi and the BJP and may hope at best to dent their commanding majority in parliament.”

Later that month, I heard from a correspondent who told me that — contrary to the conventional wisdom — the Opposition would not just dent, but end, the Bharatiya Janata Party’s majority in Parliament. This was the journalist, Anil Maheshwari, who knows northern India intimately having lived in and reported from the region for several decades. Maheshwari has also published several books on contemporary history, among them a co-authored study of Indian elections carrying the title, The Power of the Ballot.

On February 25, Anil Maheshwari wrote to me: “I am afraid that your apprehension is misplaced. Based on ground realities, which left/liberal[s] fail to see…, the BJP may get around 230 seats.”

A week later, Maheshwari wrote saying: “I must add that Modi, with dictatorial traits in his political nature, suffers from indecisiveness. [He] has failed to trim the tenure of many members of the Lok Sabha. This development strengthens my submission that the strength of the BJP may be reduced to 230 seats.”

On March 18, Maheshwari sent me another mail, which read: “I reiterate 230 seats for the BJP (30 out of 80 in U.P.). There is simmering discontentment among the voters. There is discernible hubris among the BJP voters… Notwithstanding my reservation about Rahul Gandhi’s capability, he is the only leader among the non BJP parties out on the road, attracting an impressive crowd.”

Anil Maheshwari’s predictions were offered more than a month before the election began. After the first two phases of voting, some commentators argued that the pollsters may have erred in their belief that the BJP would gain a comfortable majority on its own. These public voices are now being justly hailed for going against the grain. I trust I may be allowed to acknowledge prescience offered in private too.

In myself hoping — against hope — for a coalition government back in July 2023, I had offered this justification: “India is too large and diverse a country to be run in any way other than collaboration and consultation. However, a large majority in Parliament encourages arrogance and hubris in the ruling party. A prime minister who commands such a majority tends to ride roughshod over his cabinet colleagues, disrespect the Opposition, tame the press, and undermine the autonomy of institutions, and — not least — disregard the rights and interests of the states, particularly if they are ruled by a party other than the one headed by the prime minister.”

This assessment was based on my own life as a citizen of the Republic. Long before Narendra Modi became prime minister, I had witnessed brute majorities encourage authoritarian tendencies in both Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi. On the other side, I had seen how the press was freer, the judiciary more independent, federalism more robust, and regulatory institutions less prone to capture during the years when coalition governments were in power.

Between 1989 and 2014, no single party enjoyed a majority in Parliament. This period saw seven prime ministers, of which four — V.P. Singh, Chandra Shekhar, H.D. Deve Gowda, and I.K. Gujral — were in office for less than two years. On the other hand, in this period, three prime ministers served at least a full five-year term. These were P.V. Narasimha Rao, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and Manmohan Singh.

Now, in his third term, Modi has joined this select list, serving as prime minister without his party enjoying a majority. However, while each of his predecessors was wired, both by experience and temperament, to effectively run a government with support from other people and other parties, Modi is not. Narasimha Rao had served in both Indira’s and Rajiv’s cabinet for long periods before becoming prime minister. Vajpayee had been foreign minister in the Janata Party government led by Morarji Desai before becoming prime minister himself. Singh had served as finance minister under Rao before ascending to the top job. Further, Rao, Vajpayee and Singh had also spent periods out of government as Opposition MPs.

It is true that in his many years as a pracharak and a party organiser, Modi had worked with or even under other people. But ever since he entered electoral politics, he had not. He had never been a mere MLA or MP, and not even a minister at state or Central levels. All he had known since 2001 was how to be chief minister or prime minister. Indeed, for the past twenty-three years, he had only known life as Big Boss, Top Boss, Sole and Supreme Boss.

Both as chief minister and as prime minister, Narendra Modi constructed a colossal personality cult, presenting himself as the man, or leader, who would single-handedly take first his state and, then, his country towards prosperity and greatness. In pursuit of this personalisation of power, he asked for, and always got, submission and subservience from his cabinet colleagues in Gandhinagar and in New Delhi. In both the state and the Centre, he has always claimed exclusive credit for any new project launched or completed by his government, be it a bridge, a highway, a train station, food subsidies, or whatever.

In his narcissism, Modi is worlds removed from the prime ministers who had run coalition governments before him. Rao and Singh had understated and self-effacing personalities. Vajpayee had more charisma and popular appeal, yet he never remotely considered himself the epicentre of his own party, still less of his government or his nation. All three were thus geared, by experience and temperament, towards working in a collaborative and consultative manner with their cabinet ministers, and even, to a certain degree, with the Opposition.

By all accounts, the prime minister himself fully expected to win a hattrick of victories, announcing in advance that, on taking office afresh, he would swiftly unveil an agenda for the first hundred days of his new term. The Economic Times proclaimed on May 10, “Modi 3.0 aims at 50-70 goals for 100 day agenda”. Three weeks later, on June 2, the Hindustan Times asserted, “PM Modi to hold a review meeting with top officials on the first 100 days of his third term”. Note that the plan was to hold meeting with officials only; the ministers were expected to remain, as they had been for the past twenty-three years in Gandhinagar and New Delhi, without a voice on how the government should be run.

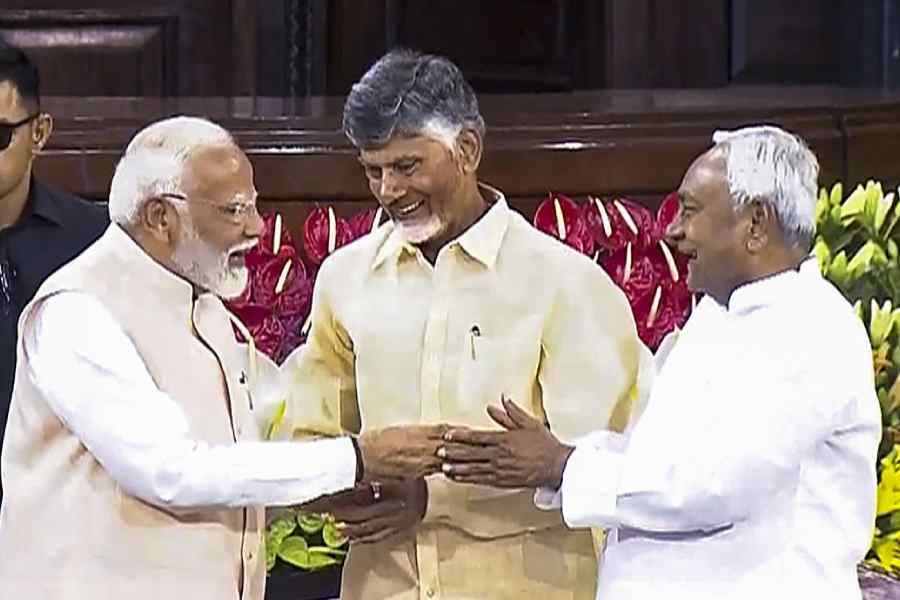

As it turned out, however, what was thought to be Modi 3.0 has unexpectedly become NDA 2.0. This raises the question; can an autocrat become a democrat? Can someone who so recently claimed that he is god’s representative on earth come to regard himself as human and fallible and take advice from, as well as give credit to, other people? Can a majority-less Modi emulate Rao, Vajpayee and Singh in giving more power to his cabinet ministers, in having a less overbearing attitude towards his MPs, in being more courteous to the Opposition, in according respect to state governments not run by his party?

A considered answer to these questions may take several months or even several years to reveal itself. In the short-term, I expect a symbolic moderation of Narendra Modi’s style of rule; as in a slightly greater space for debate in Parliament, perhaps, and less obnoxious behaviour by governors in Opposition-ruled states. Senior ministers — as well as Modi himself — may stop demonising Indian Muslims in public. But whether there will be substantive changes in the mode of governance remains to be seen. The instinct of this prime minister is to centralise and dominate, a tendency reinforced by the two decades (and more) of unbridled power that he has thus far enjoyed.

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in