In less than a fortnight, by the afternoon of November 10 to be precise, the outcome of the Bihar assembly election will be known. There will be the usual flurry of momentary excitement as the political pundits assess the results and speculate on the likely consequences of the verdict both regionally and nationally. Without anticipating the mood of the electorate in a state which once had a reputation for violence and election irregularities — but has since redeemed itself quite dramatically — it would be tempting fate to suggest that the consequences of the assembly election may not be far-reaching.

Yet, however routine, every assembly election is significant in a number of ways. The Bihar vote, too, will be no different and may offer some pointers to the next round of assembly elections in the summer of 2021, at least in the eastern state of West Bengal.

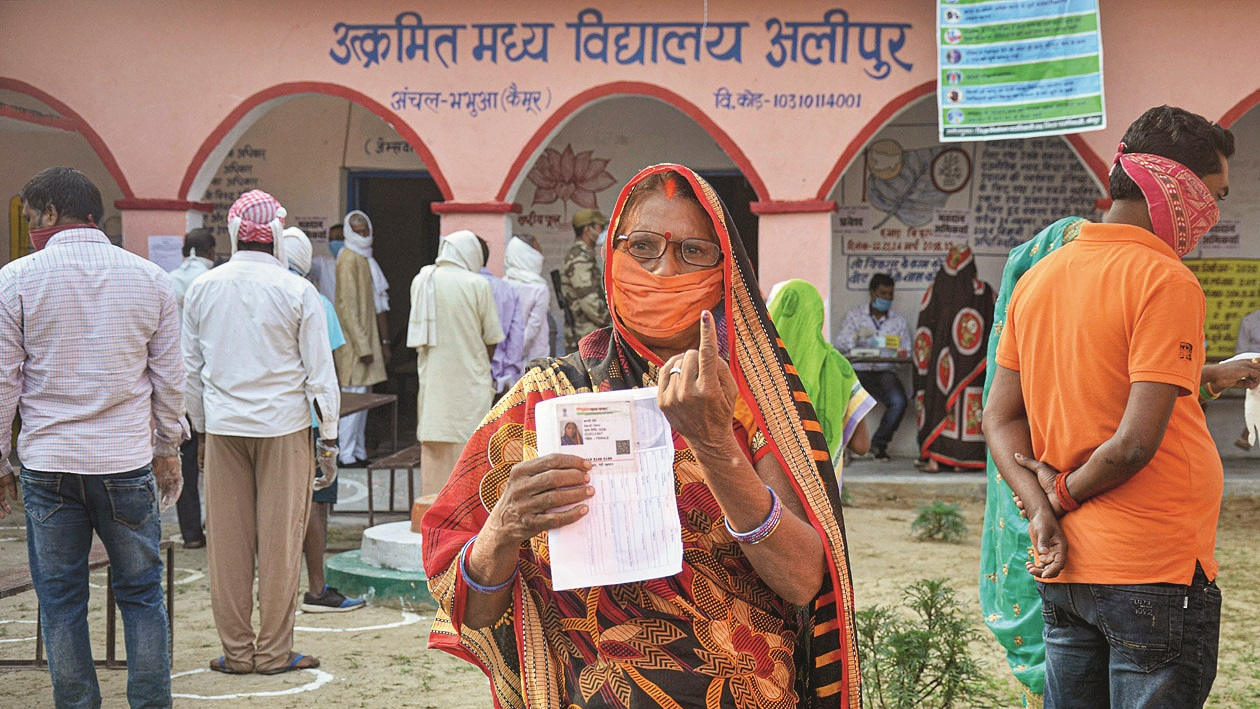

The most significant aspect of the Bihar election that will impact national decision-making is centred on the poll process during the Covid-19 pandemic. With the vaccine still awaited, the health protocols are centred on the principle that human contact should be minimized as far as possible. This principle by its very nature goes against the functioning of electoral democracy that involves optimizing contact of political workers with voters. Additionally, unlike the West where campaigning has become more focussed on media and doorstep contact, Indian elections are conducted in a carnival atmosphere. Mass meetings, for example, have a significance not merely to communicate political messages to voters but the scale of attendance is also treated as a measure of public support, not least to entice undecided voters anxious to be on the winning side. In attempting to evolve fresh guidelines to cope with the challenges of Covid-19, the Election Commission had attempted to balance mass contact with social distancing. This was always going to be an impossible task and its success depended substantially on public awareness and political restraint. The experience of the campaign so far suggests that the faith in online meetings substituting outdoor mass meetings has been totally misplaced. Nearly all the political parties that had banked on virtual rallies have revised their plans and reverted to organizing carnivals. The images of public meetings addressed by the Rashtriya Janata Dal’s Tejashwi Yadav and the Lok Janshakti Party’s Chirag Paswan, for example, suggest that the fear of the virus has been subsumed by the desire to demonstrate the quantum of public support. Predictably, this has worked to the disadvantage of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the chief campaigner for the National Democratic Alliance in the state. As the host of the prime minister, the state Bharatiya Janata Party has had to make a more visible show of social distancing than its rivals. Consequently, in visual terms, Modi’s rallies which, in earlier years, have been the high points of election campaigns have been less spectacular. The BJP has had to compensate with rallies by Bhojpuri stars such as the Delhi parliamentarian, Manoj Tiwari.

The next few weeks will indicate whether the widespread fears of religious and political festivals leading to a spike in Covid-19 infections are legitimate. Going by the experience of post-Onam Kerala, the concerns seem real and explains why the prime minister addressed the nation to advise utmost care and restraint as long as the pandemic persisted. In political terms, what will be significant is the impact of the pandemic on voter turnout. If, as is being suggested, the fear of the deadly virus becomes a deterrent to voters in the 50-plus age group, will that be inimical to the NDA or its opponents? Moreover, anecdotal evidence argues that Muslim communities are relatively less inhibited in the conduct of normal public life during the pandemic than other communities. If this principle translates to queueing before polling booths, there is a possibility that the strategic Muslim vote in Bihar will be far greater than its population share. This does not augur well for the NDA.

A second feature of the Bihar election that has a larger bearing is the voters’ attitude towards incumbency in extraordinary situations. In the past, during elections held in moments of great national stress, such as conflicts with foreign powers, voters have been inclined to give resolute support to the governments of the day. In the recent past, as happened in the Uttar Pradesh assembly election of 2017, even an extraordinary measure such as demonetization led to voters supporting the move. This support was contrary to media reports that suggested a groundswell of anger against the economic dislocation caused by demonetization. In this Bihar election, interest will be centred on the way in which the economic hardships suffered by migrant workers — a very large number are from Bihar — will play out. Going by media reports, many of the development initiatives undertaken by the chief minister, Nitish Kumar, in the past 15 years are being overshadowed by the anger of migrant workers over difficulties experienced in the wake of the 21-day national lockdown in March and April this year. This is also borne out by opinion polls indicating that the NDA’s possible tally is being pulled down by a tide of anti-incumbency against the chief minister — as happened in Rajasthan in 2018 and in Jharkhand in December 2019.

Certainly, the anger against the man who was in the past lauded for his sushasan (good administration) has created an awkward situation for the NDA and the BJP at the Centre. LJP’s Chirag Paswan has, for example, walked out of the NDA in Bihar but remains a committed supporter of Modi at the Centre. On the ground, a very large number of the LJP candidates contesting against the Janata Dal (United) nominees happen to be BJP rebels. The bush telegraph would have people believe that Paswan has been intentionally promoted by the BJP to bring Nitish Kumar down by a few notches and ensure that the BJP’s final tally exceeds that of its senior coalition partner. If this indeed happens and there is a fractured verdict, Bihar could be plunged into political uncertainty.

Any possible uncertainty, in turn, could have an impact on political alignments at the Centre. After the Shiromani Akali Dal walked out of the NDA over the legislation on agricultural marketing reforms, there has been some gloating in Opposition circles over the systematic truncation of the ruling alliance at the Centre. If the NDA secures a clear majority in Bihar and Nitish Kumar resumes his role as chief minister, the impact is certain to be minor and manageable. At best, the induction of Paswan in the Modi ministry may be confronted by a JD(U) veto, leading to the LJP looking for other openings. However, in the event of a fractured verdict, the NDA is certain to experience a significant churning.

Finally, the Bihar verdict is likely to have some impact on neighbouring West Bengal but only if the NDA registers a conclusive victory. The BJP is on an expansionist spree in its fight against Mamata Banerjee and needs powerful defectors from the Trinamul Congress to bolster its clout in south Bengal. An NDA victory could begin a rush to embrace the BJP before the year is out, a development that will leave the ruling TMC beleaguered and desperate to cling on to power. In Bengal, unfortunately, political realignments are invariably accompanied by violence on the ground. Unknown to him/her, the voter in Begusarai and Samastipur could, therefore, mould political behaviour in East Midnapore and Howrah districts.