The contrast in the reactions to two landmark decisions on the contentious issue of reservations tells us a great deal about ourselves as a people and society, of our understanding of privilege and deprivation, of our commitment to justice and equality, and, most of all, of what we choose to see and not to see.

In 1990, when the V.P. Singh government decided to implement the Mandal Commission recommendation of providing 27 per cent reservation to socially and educationally backward classes (also known as other backward classes) in Central government jobs and educational institutions, the country was wracked with turmoil and unrest.

In North India, in particular, students belonging to the upper castes took to the streets to protest what they claimed was as an attack on “merit”. V.P. Singh, whose anti-corruption crusade had made him a middle-class hero, became a hated figure overnight.

Given the demographics of Indian society, where the scheduled castes (Dalits), scheduled tribes (adivasis), and socially and educationally backward classes far outnumber the dominant upper castes, no political party could openly oppose the new quotas. But the Bharatiya Janata Party found a devious way out. It sought to counter the challenge of Mandal with kamandal — shorthand for the politics of religious polarization that was unleashed in the wake of V.P. Singh’s decision.

Even as towns and cities in the Hindi belt were convulsed with anti-Mandal protests, L.K. Advani set off on his rath yatra to campaign for the construction of the Ram temple in Ayodhya where the Babri Masjid stood. The decision to implement quotas for OBCs, in short, led to a series of events that changed the political landscape of India for decades to come.

Compare that with what happened in the closing days of the winter session of Parliament last week. The Narendra Modi government, out of the blue, brought a Constitution amendment bill to provide 10 per cent reservation in jobs and educational institutions for “economically weaker sections” in the general category. Seldom has a piece of legislation of such significance found such an easy and quick passage in both houses of Parliament.

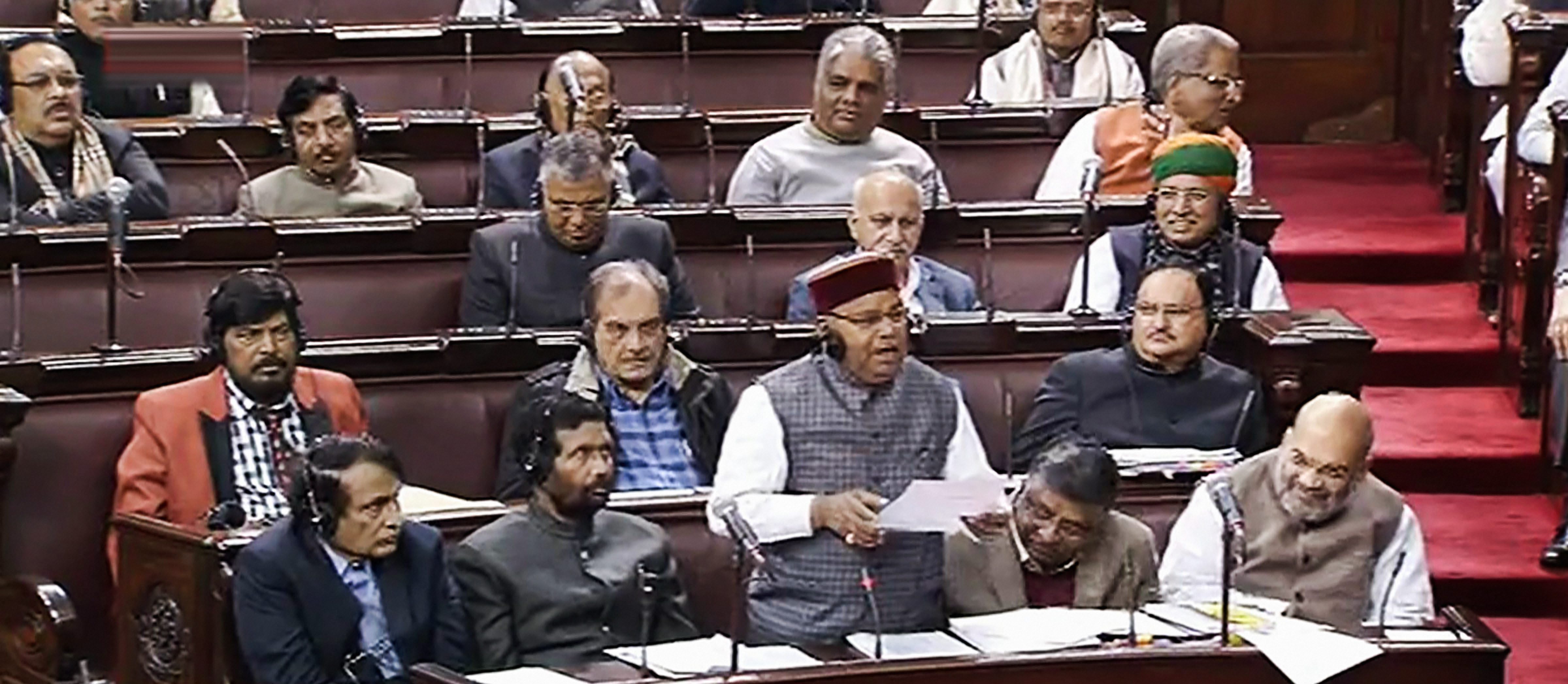

The Lok Sabha passed the Constitution (124th amendment) bill, 2019 near unanimously last Tuesday. The Rajya Sabha did the same the next day. Only four parties — RJD, DMK, AIADMK, and AIMIM — opposed the bill.

Almost every speaker from the Opposition benches attacked the government for the timing of the bill and accused it of political expediency. But hardly any of them — not the Congress nor the Left, not the Samajwadi Party or the Bahujan Samaj Party — questioned the underlying ideology of the bill. Since some of these parties — including the Congress, the CPI(M) and the BSP — had advocated quotas for the poor among the forward castes, they were in no position to oppose it. Outside Parliament, too, there was no adverse reaction to the legislation. When OBCs were given statutory quotas in 1990, upper castes had been up in arms over the alleged assault on “merit”. Even though the general category was now reduced to 40.5 per cent — breaching Supreme Court directives that reservation should not exceed 50 per cent — there was no adverse reaction from civil society.

Yet, in spite of the broad political support it has received, the latest bill passed by Parliament constitutes a brazen assault on the basic structure of the Constitution as envisioned by the founding fathers of the Indian republic. It is also a pernicious attempt to deny the centrality of caste in making India a most unequal and unjust society.

Every country has its share of the poor and governments offer a range of social welfare measures — in the form of scholarships, subsidies, doles — to help them improve their lives. But caste inequality is peculiar to India and the Constitution-makers took full cognizance of this. Taking into account the “historic injustices and inequities” that were prevalent in India over centuries, wherein entire groups of people were subjected to systemic deprivation and discrimination on account of their caste, the Constitution envisaged special provisions for their advancement.

In 1992, a nine-judge bench of the Supreme Court in the Indra Sawhney judgment upheld the principle that social and educational backwardness rather than economic deprivation was the constitutional criteria for reservations. Striking down quotas for poor among the upper castes, the verdict noted that, “a backward class cannot be determined only and exclusively with reference to economic criterion. It may be a consideration or basis along with and in addition to social backwardness, but it can never be the sole criterion...”

The principle behind affirmative action was to give castes that had been denied access to education the opportunity to have, in Ambedkar’s words, a “look in” into administration and power structures of the state. Economically weaker individuals belonging to the upper castes never faced such scripturally mandated exclusion and discrimination.

Since India chose to be a democracy based on universal suffrage and those belonging to the SCs, STs and OBCs (or the “untouchables” and the shudras in the Manu-ordained Hindu caste system) form an overwhelming numerical majority, no political party can afford to openly dismantle caste-based quotas. The Dalits and OBCs have also won a measure of political empowerment as a result of the one man-one vote principle.

Yet, the sad truth is that even seven decades after Independence, the hegemony of a few upper castes — to which many of us belong — has remained largely intact. We, the privileged, continue to control the levers of power, wealth and communication — in spite of being a minority in terms of the numerical strength of our castes. Although the last caste census took place back in 1931, one has to be willfully blind not to see the upper caste domination — and the resultant lower caste exclusion — across professions that persists to this day.

In spite of the policy of reservations, upper castes dominate government. As the Samajwadi Party leader, Ram Gopal Yadav, pointed out in the Rajya Sabha last week, of the 81 secretary rank officers in the government of India, only two belong to the scheduled castes, three to the scheduled tribes and none are from the other backward classes. Even lower down the bureaucracy, the grip of the upper castes far exceed that of others.

In professions sans mandatory quotas — judiciary, media, business, hospitality, private education — the situation is far worse. Even within the ‘general category”, it is the handful of savarnas (Brahmins, banias, kayasthas, kshatriyas) who dominate the white collar professions. Conversely, it is rare to find members of their ranks among manual workers such as masons, carpenters, labourers or rickshaw pullers.

Reservations are no panacea against caste inequality. It requires a complete overhauling of the education system by providing free and common schooling to all for any sort of level playing field to emerge. But the first step to address any curse is to acknowledge that it exists. We resolutely refuse to do so.

Most of us attribute “merit” and hard work for our superior status in life — oblivious to the inherited privileges that accrue from being born into a savarna caste. The outrage of people like us during the anti-Mandal agitation nearly three decades ago brought out an irony: those who have gained on account of their caste tend to be “caste-less” and find the very mention of it repulsive; and those who have suffered as a result of their caste and are painfully aware of it are dubbed “casteist”.

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh at one end and the Marxists on the other, both seek to deny the primacy of caste and the pernicious role it continues to play in determining the opportunities for emancipation and advancement. If the RSS seeks to camouflage the reality of caste under the cloak of a “Hindu” identity, the Left undermines it by focusing on class — ignoring the debilitating internalization of inferiority (or superiority) that makes caste more than merely an ossified class.

Such is the weight of upper caste domination over both mind and matter that many subaltern parties (such as the BSP) have backed quotas for the poor among forward castes in order to minimize the stigma they face on account of being “quota” recipients. And in spite of winning political power from time to time, these parties have not been able to dismantle the system of education or administration that reinforces deep and subliminal caste prejudices.

Unless the Supreme Court strikes it down, the 10 per cent quota will be an abomination on the Constitution, an ahistorical step backwards in India’s painfully slow journey towards a more equal society.