Predatory pricing has been a contentious issue in the telecom industry ever since Reliance Jio launched its service with virtually zero tariffs in September 2016 through a welcome offer that was extended for several months thereafter. The legacy players in the business — Airtel and Vodafone — had cried foul and tried to persuade the telecom regulator to stop what they believed were predatory tactics by an entity that could draw its resources from the cash mountain created by India’s largest private sector conglomerate. The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India not only rejected those pleas but also chose to buy Jio’s argument that the older telecom players were offering price discounts and segmented offers to their most-valued customers to dissuade them from migrating to the newbie’s service, effectively violating a stipulation made in 2002 that no telecom provider could have more than 25 plans, pre-paid and post-paid, at any given point of time. The double whammy meant that the older players, struggling for survival after making large capital investments for spectrum and 4G equipment without the benefit of decent returns due to lowball, competition-induced tariffs, started to wallow in losses.

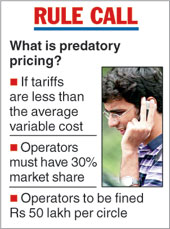

Last week, the telecom tribunal stepped in to restore a semblance of sanity and fairness in the interpretation of predatory pricing. The real bone of contention was Trai’s definition that the charge of predatory behaviour could only be levelled against a player that had acquired significant market power. Under the regulator’s definition introduced through a change in regulations in February this year, a service provider would be considered to have significant market power only if it had a share of 30 per cent of the total activity in a relevant market. Total activity, the regulator said, would be determined on the basis of either subscriber base or gross revenue. The new criteria meant that Jio was off the hook. The tribunal said the change in definition provided “artificial protection” to a telecom service provider that “may have the capability and intent to destabilize the sector through predatory pricing before it attains the defined status of SMP”. It also stated that there was evidence that Trai had unnecessarily abdicated its regulatory powers by adopting a subjective yardstick and non-transparent methods to determine predatory behaviour. It has now directed the regulator to reconsider the provisions relating to the concepts of SMP and non-predation within the next six months. It has been asked to carry out a consultation process on the other contentious subject of price discounts and segmented offers.

One crucial reason for setting aside the amendment in the tariff rules was the fact that Trai was trying to infringe on the jurisdiction of the Competition Commission of India, which usually adjudicates on such disputes. The tribunal’s ruling may persuade the regulator to abandon its obvious biases and act in a more even-handed manner.