Among the reasons I write for The Telegraph is that this newspaper lets me say what I want. A second is that my mind was quickened and shaped by the intellectuals of Calcutta, and although it is thirty-five years since I left the city, I cannot stop myself from conversing — and arguing — with them.

A Calcutta intellectual with whom I have had many arguments — in public and in private — is the distinguished political theorist, Partha Chatterjee. Partha gave me my first job, at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences —then located at Jadunath Bhavan, in Lake Terrace — and I suppose there is some sort of Freudian element to our relationship, with the former disciple seeking to shake off the influence of his erstwhile mentor.

Partha Chatterjee and I have argued about (among other things) India’s most beloved sport. Back in the 1990s, the naturalized Bengali, Jagmohan Dalmiya, announced that he wished to abolish the draw from Test cricket. He claimed that paying spectators always wanted a ‘result’; hence he proposed to convert Tests into a longer version of limited-overs cricket, with each side getting 90 overs in the first innings, and 60 overs in the second. I wrote an anguished denunciation of Dalmiya’s proposal in The Telegraph, insisting that the draw had a charm and dramatic intensity uniquely its own, as exemplified by the stirring tales of how Hanif Mohammad and Sunil Gavaskar had batted for hours and hours to deny the other side a win. Partha Chatterjee immediately wrote a rejoinder in these columns, dismissing me as a woolly-headed romantic who would not recognize the changes unfolding before his eyes.

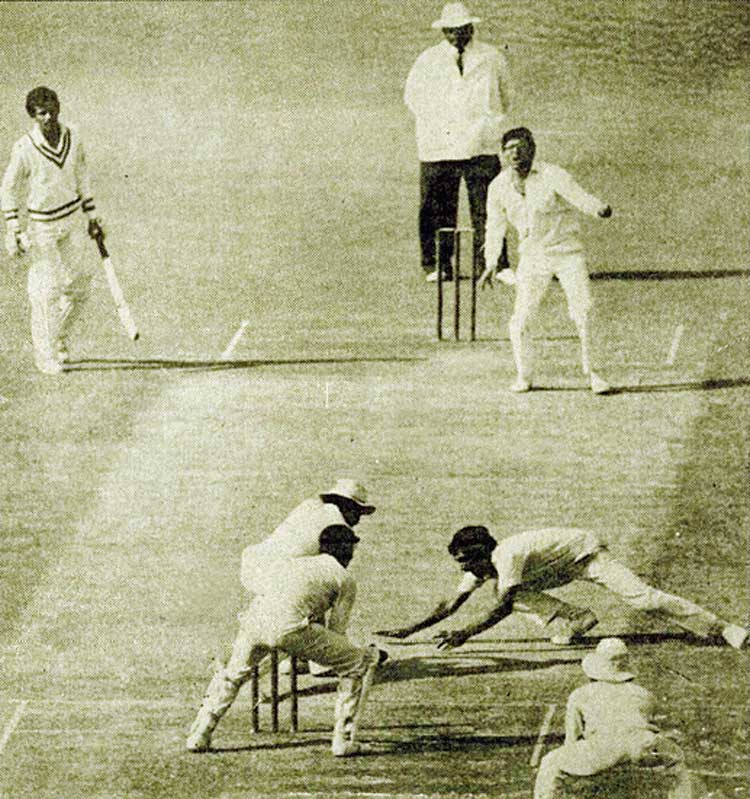

In my years in Calcutta, Partha and I had many addas about history and politics. And some about cricket too. Usually, we were joined by Rudrangshu Mukherjee, another Calcutta intellectual, whose passion for India’s favourite sport is much less known than his works of historical scholarship. In terms of cricketing fandom, Partha and Rudrangshu had two great advantages over me. They were older, so they had accumulated more stories about the game. And they grew up in Calcutta, which meant that from the time they were little boys they had access to a great cricketing venue, indeed the greatest of them all outside Lord’s and the Melbourne Cricket Ground, namely, the Eden Gardens. They had been to Test matches there since the 1950s, and had therefore watched Hazare and Umrigar, Sobers and Harvey, in the flesh, whereas I had merely read about these giants of the game.

On my side, I had one great advantage over Partha and Rudrangshu. This was that my state, Karnataka, had in the past decade accumulated a string of Ranji Trophy victories, while their state, Bengal, had last won the championship during the time of the British raj. In their growing up years, my friends had seen Bengal reach the Ranji final no fewer than five times, and lose on each occasion. Four of these defeats had been at the hands of Bombay, which had won the Ranji Trophy every year from 1958 to 1973. Whereas I had actually been at the Chinnaswamy Stadium when Karnataka beat Bombay in a Ranji semi-final in March 1974, preparatory to their defeating Rajasthan in the final. Karnataka had won the trophy twice more in the subsequent decade.

It is hard, in these days when the main domestic tournament is the egregious Indian Premier League, to communicate to the younger generation what the Ranji Trophy meant to cricket fans who are now on the wrong side of sixty. In the 1960s and the 1970s, when there were so few Test matches, and no live television, what mattered most to us was the fate of our state sides. Ranji matches attracted crowds of twenty and thirty thousand, with many more following them on radio and via newspaper reports. Partisan loyalties ran deep. Tamil cricket fans insisted (against the evidence) that Venkataraghavan was a better off-spinner than Prasanna, while Bengalis claimed (also against the evidence) that there was a deep-seated conspiracy to deny their cricketers representation in the Indian Test side.

Since the Ranji Trophy so strongly defined our identities as cricket fans, in our conversations of the 1980s, Partha, Rudrangshu and I spoke as much about Bengal and Karnataka cricket as about Indian or West Indian cricket. My two friends had both grown up on stories of what was Bengal’s only Ranji Trophy victory at the time, which had occurred in 1938-39, long before either of them were born. The two stars of that side were both expatriate Englishmen working as boxwallahs in Bengal. Their names were A.L. Hosie and T.C. Longfield. I believe the initials stood for Alexander Lindsay and Thomas Charles. But Partha and Rudrangshu told me that the Eden Gardens crowd referred to them, with love and affection, as ‘Amrit Lal’ and ‘Tulsi Charan’, respectively.

My Bengali friends knew of their side’s sole championship victory only at second and third hand. Whereas my side had won the Ranji Trophy several times in my lifetime, and sometimes with me at the ground to watch and cheer them. I suppose I must have communicated a certain triumphalism in those cricketing addas in the Calcutta of the 1980s. Only that can explain the contents of a mail from Partha Chatterjee that popped into my Inbox earlier this month. It was short — as Partha’s mails usually are. But while our recent correspondence has dealt with such grave subjects as the suppression of dissent and the rise of authoritarianism, this mail dealt with cricket. It ran to ten words, these being: “Bengal thrashed Karnataka! Three cheers for Piggy Lal, hip hip hurray!”

Partha’s side had just defeated my side in the semi-finals of the Ranji Trophy, and in the Eden Gardens to boot. I doubt that my friend had been at the ground, but clearly he had followed what was happening very closely, and in real-time. I had myself not paid much attention to the match. Now, from Partha’s mail, it seemed that Arun (Piggy) Lal was the manager of the Bengal team, and the internet confirmed that it was so.

I did not begrudge my old friend and first boss his happiness, or his schadenfreude rather. It had been a long time coming. Normally I would hate it for Karnataka to lose — but much rather to Bengal than to the old enemy, Mumbai, or the even older enemy, Tamil Nadu. And any disappointment I might have felt was further tempered by the fact that I had known Piggy Lal longer than I had known Partha Chatterjee. Back in the 1970s, I had played cricket for St Stephen’s College under his captaincy. Piggy went on to win sixteen Test caps, opening the batting and fielding brilliantly anywhere. He is a wonderful human being, and a very brave one too, having come through a bad bout of cancer to rebuild his life. The young cricketers of Bengal are lucky to have a man of his character and abilities to guide them.

Piggy Lal himself made his Ranji Trophy debut for Delhi, in 1974. Some years later, he got a job in Calcutta, and henceforth played for Bengal. He became a naturalized Bengali, like Amrit Lal Hosie and Tulsi Charan Longfield before him. Indeed, when Bengal won the Ranji Trophy for the second time, in 1989-90, it was chiefly due to a match-winning knock from my old college captain, with every run from his bat cheered along by a crowd of 30,000 shouting ‘lal salaam’.

The communists are no longer in power in West Bengal. And Ranji finals, nowadays, attract meagre crowds. This year’s final, with Piggy Lal as coach rather than as player, was played at Rajkot. Away from home, the Bengal team struggled, and eventually lost. My feelings about this result are mixed. On the one hand, I feel sorry for my friends, Piggy Lal and Partha Chatterjee. On the other hand, Saurashtra had never won the Ranji Trophy before, and it is nice that they now have their names on the trophy, to join (among others) Bengal and Karnataka.

One final word. The IPL has now comprehensively replaced the Ranji Trophy as the country’s premier cricket tournament. But despite the hype around the IPL, I do not think that fans’ loyalties to their teams are really so deep and enduring. I somehow doubt that two friends who now follow Royal Challengers Bangalore and Kolkata Knight Riders, respectively, will be arguing about their teams thirty or forty years hence.