In a short essay that I have returned to again and again to reaffirm to myself the recurrent inadequacy of language in conveying the bizarre hyper-reality of the world around us, Salman Rushdie wrote: “What kinds of life should we call ‘ordinary’, here in the late twentieth century? What is ‘normal’ in these abnormal days? For many of us, any definition of the quotidian would still include notions of peace and stability. We would still, perhaps, wish to picture everyday life as rhythmic, based on settled and repeating social patterns. Ryszard Kapuscinski’s work seems to be based on his knowledge that such conventional descriptions of actuality are now so limited in application that they have become, in a way, fictions.”

I have been thinking of Vinayak Savarkar and his frequent flying out of his kaala paani captivity on bulbul, or nightingale, back. I have been thinking what sort of things the current and coming generations of Indians will end up reading. I have been thinking what set of words will be able to convey to us the sense of those flights in the truest possible way. Will a simple declarative sentence do it? Are we to understand it as a metaphor? Is it meant to be hyperbole? Is it synecdoche for bulbul, or for Savarkar, or pray, for the Andaman Cellular Jail? Is it some fable or a morality tale with a lesson conveyed at the end? Is it a joke? Is it farce? But how could that be, because it was put into a school textbook. But what would you say about a school textbook that says Savarkar used to fly out of the Andaman Cellular Jail on bulbul back?

There are far too many things in our lives now that beg the question: what would you say? I am not being facetious. That’s the other peril of asking simple, straightforward questions and employing ordinary language to ask them these days. Between dispatch and delivery, there is likely to be a huge loss in translation.

Q: So what would you say about a school textbook that says Savarkar used to fly out of the Andaman Cellular Jail on bulbul back?

A: So then, you must also be among those who do not believe Pushpak was the first aircraft.

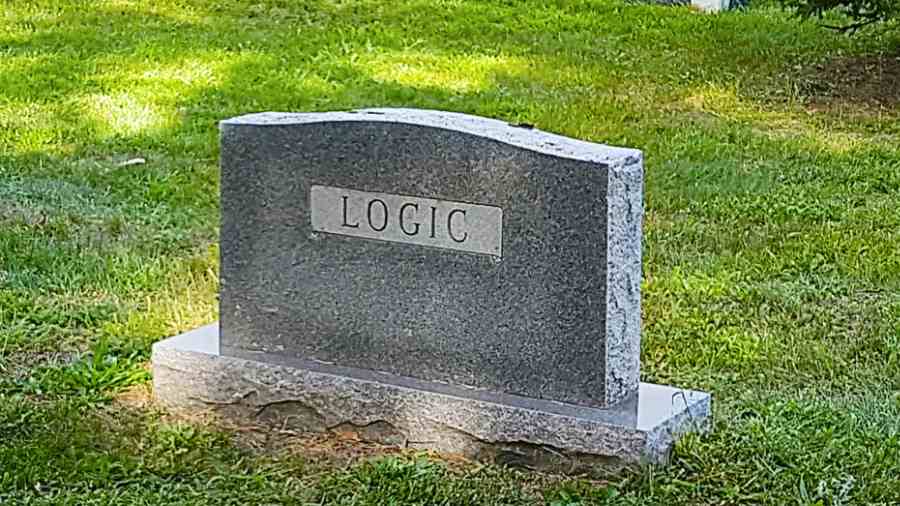

The assault on reason, logic or just plain common sense has been unrelenting and of an astounding nature these past years. You know just how when the Union health minister endorses a dubious cure kindled by a courtier baba-businessman in the middle of a killer pandemic. You know just how when the minister for education stands up in Parliament and pronounces astrology to be the highest science. You know just how when the prime minister preens to the nation over how fighter jets used cloud cover to dodge enemy radars, strike and return home safe.

We must fear for a nation so fed. We must fear for what it is consuming and what it will cough up. We must fear, equally if not more, for what it is exultantly rejecting under the tutelage of those whose vested interest it has become to eschew good sense.

Some of the best-known writers and public voices — Indian as well as those with a strong India connect — spelt out their concerns about India heading into harm’s way — away from its essential pluralisms, away from democratic mores, away from most of what has held such a diversity magically under one flag, singing one anthem. The collection of essays, marked for India’s 75th Independence Day, had little resonance beyond the constituency of believers in the India that the Constitution defines. Nobody in the government seemed to take note; if they did, it would have been with a sense of affront and indignation — just who the heck are these people and what allows them preaching rights? Previously, the powers and their vociferous votaries have spat out similar loathing at a string of eminences — Amartya Sen, Raghuram Rajan, Abhijit Banerjee, Arundhati Roy, Irfan Habib, Romila Thapar to name just a few. Thapar, probably the best known and respected historian we have, was also asked by authorities at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in 2019 to submit her curriculum vitae in order that they could re-evaluate her status as professor emerita; happily, she said she couldn’t be bothered. She’s said for anybody who cares to listen she does not like (Narendra) Modi’s India. Modi’s India has not remotely indicated it is hurt or bothered. It is not interested in Thapar; it is, in fact, uninterested in her, to say the least. The Concerned Citizens’ Group, a collective of widely-respected retired diplomats and bureaucrats, regularly writes to the government on critical corrections. Nothing tells us the government pays any attention. Part of the reason is that Modi’s India does not believe in reading, much less lending half a ear to another view; it is brusque in its rejection of what it puts down as ‘intellectuals’ (especially those that employ English), it is disdainful of the effort at distilled analysis and knowledge, it professes nearly no commitment to learning probably because that requires time and effort and talent. Even M.S. Golwalkar’s Bunch of Thoughts, unabashedly inspired by Nazi thought, is perhaps too voluminous a text. The fellowship of Modi prefers to gulp what it is spoon-fed in dollops — the lucid dog-whistle or stuff like cloud cover as a means of dodging radars. The Bal Narendra tales must rank high on their reading list — it is comic-form, simple as Chandamama stories. There is a volume afloat called Modi@20 which has been billed as belonging to a higher station than the Bhagavad Gita. Or, the most preferred of all, the wisdoms of a university called Whatsapp: Gandhi was rightly killed by Nathuram Godse, the real patriot; Nehru was born in a brothel and died of syphilis after spending a whole life as playboy; if not taken in hand right away, Muslims are just a few years away from overtaking the Hindu population of India. Such is the prudence on parade in virtual hyper-reality.

We do not live in ordinary times. These are times in which we applaud murder and wrap its actors in the national flag. These are times in which we order garlands and sweets to welcome convicted rapists and butchers of fellow humans as they walk out of jail and line up to be felicitated. (Try dipping into Savarkar’s Six Glorious Epochs of Indian History and you will probably find the context to why the violators of Bilkis Bano have become objects of celebration.) These are times in which it outrages few that such a thing can happen. These are times that give truth to Savarkar flying out of his jail cell on bulbul back; the extraordinary has left the ordinary so ruefully ruptured it cannot be simply articulated.