When does an ethical anachronism churn guilt? When you enjoy an artwork with values that clash with those in which your body lives? But you’re also a creature of the present. You cannot but feel guilty about the speck of a self that belongs to a world of lore that gave you a heart out of joint with its own time.

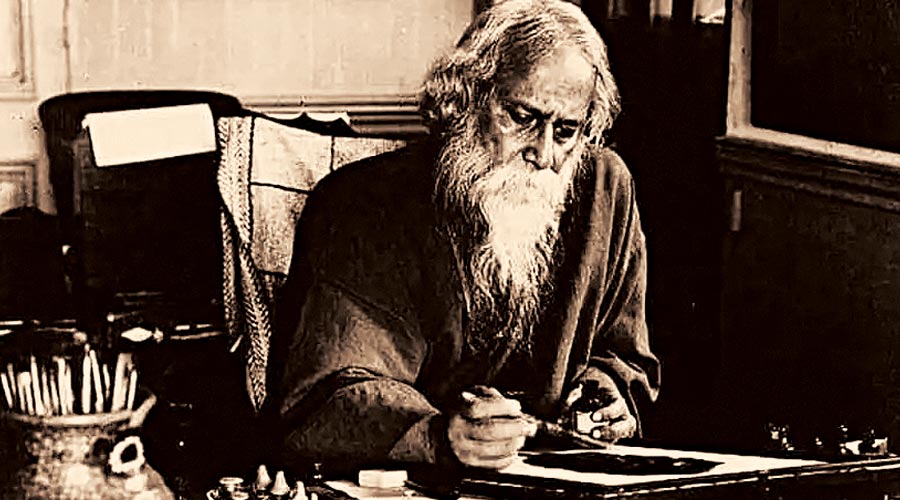

‘Timeless’ is one of the clichés used the most to describe Rabindranath Tagore. Like most clichés, it holds much truth. But I think every serious reader of Rabindranath has experienced the guilt of an anachronistic sensibility, of loving something they know they cannot love anymore. My most recent jolt came from the experience of translating the short story, “Shubhodrishti” — “The first look”, in my English version — for the new Oxford World’s Classics edition of Rabindranath’s stories that is being edited by Sumit Chakrabarti. In this story, a wealthy man who is at least in his mid-twenties, very possibly older, stares at a local girl in a village where he is ravaging peace with his hunting expedition. She is barely out of girlhood.

“One couldn’t quite tell her age. Her body had bloomed but her face looked young, as if nothing of this world had touched her yet. She seemed unaware of the fact that she had become a woman.”

One puts away the violence of the blazing gun (which he carries) against the vulnerability of the two ducks (which she carries); likewise with aristocratic arrogance intruding into the lives of local villagers. But what does one do with this gaze, soon to become a fascination, with this rather un-Nabokovian Lolita?

Kantichandra, the gazing man, is a whole lot younger than Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert. And we still have family memories of marriages between older men and young girls. My own grandmother was 17 years younger than my grandfather, and I suppose such memories are fairly common. All of us who nourished our readerly sensibilities on 19th and early-20th century Bangla literature know the disorienting homeliness of the child bride. It was Rabindranath’s own lived experience.

How does one recreate this disorienting familiarity for the 21st-century reader in English across the world? At a time when ethical anachronisms have led to much cancellation of culture? How does one translate this moment of disturbing beauty without making it sound creepy?

Is Rabindranath as placeless as he is timeless? If he is the world-poet, do his fictional moments travel across place as easily, especially those that unsettle a 21st-century translator of his, one who received his language as an inheritance? “Style, then,” writes the novelist, Tim Parks, in an essay arguing against globalization in literature, “involves a meeting between arrangements inside the prose and expectations outside it.” Why values, you can’t even have a real understanding of style without the knowledge of the community behind it: “You cannot have a strong style without a community of readers able to recognise and appreciate its departures from the common usages they know.”

Parks’s essay, written as part of the ‘literary activism’ movement led by Amit Chaudhuri, is a powerful caveat against the prevalent fetishization of the idea and the practice of ‘global literature’. This is the absurd claim made by curators of glitzy, transnational literature festivals, that ‘If a work is good it will reach out to everyone the world over.’ Which is fantastic news for media and publishing conglomerates but not so much for true style, organically rooted in place and often lost in translation. Such global literature, Parks writes, “might go for very obviously and internationally recognisable ‘literary styles’, elevated registers, fancy adjectives, and elaborate syntax. But they will not be styles that require intimate knowledge of a particular literary context.”

The hidden contradictions of a deeply localized sensibility come out with the greatest beauty in Parks’ reading of Henry Green — in the alliterative rhythm of Green’s syntax, his staccato use of monosyllables, and, most crucially, in his patchy use of working-class dialects of northern England in the 1930s. When Parks, an accomplished translator of Italian literature, back-translates into English the Italian translation of the same passage from Green, every detail is preserved but “the text no longer distinguishes itself from others linguistically.” It can now offer only what its skeleton holds: “its plot, its idealistic tendency perhaps, its moral” — the latter qualities highly prized by the Nobel Prize Committee.

The provincialism of great art can be hard to accept. Doubtless, its humanity travels across time and place, but what cannot travel is just as important as what does. Literature, movies, and music can be imagined, just like smartphones and pandemics, as slick travellers through global news and export. But thankfully they are far more erratic and resistant. The resistance and the unpredictability make for poor hype and sales, but sometimes they also hold their greatest power, as I realized with Rabindranath’s story, shockingly so.

It is admirable when one can encase a story within a language alien to the former’s culture. I remember a recent Facebook post by one of my favourite contemporary Bangla writers, Anita Agnihotri. The post about a recently-deceased legend, Nabaneeta Dev Sen, sounds like this in my translation: “From within the familiar five-spice smell of the Bengali household, she suddenly opens a window to the streets of Brooklyn and the pubs of Austria... much that is unexpected, and yet so much woven seamlessly.” And then Agnihotri quotes the opening lines of a novel: “My friend Hannah Orenstein’s Bar Mitzva was held in the small Lutheran church at the crossing of Sepúlveda and Montana. They let it to be used as a synagogue.” And then: “How many brave young writers today would dare to open a Bengali novel with the bar mitzvah of a middle-aged Jewish woman? They would worry many times over — wouldn’t the reader just put it aside after the first few lines?

Agnihotri was commending the courage to break the boundary of language and culture. But the fact that such barriers exist speak to the organic nature of culture. Their refusal to be translated is sometimes the stubborn mark of their greatness.

Saikat Majumdar is Professor of English and Creative Writing at Ashoka University