Even as Calcutta remains glued to the grisly details concerning the death of a young student who was the victim of ragging, equally distressing news is coming from another corner of the country. Yet another ‘death’ of a student preparing for the Joint Entrance Examination in Kota, the famed coaching hub in Rajasthan, has come to light. The latest tragedy takes the toll of student suicides in Kota to four this month alone: 22 students have taken their lives this year. The grim figure is the highest that Kota has seen in the past eight years. In fact, alarm bells had started ringing way back in 2015 when a National Crime Records Bureau report highlighted a 61.3% rise in student suicides in these coaching centres. The finding was not surprising. A recent survey revealed that four out of 10 students in Kota struggle with mental health problems like depression. Evidently, the intimidating and inhuman environment in Kota’s coaching centres — students are compelled to study for about 16-18 hours a day in cramped classrooms to ace the highly competitive entrance tests with little or no means of recreation and exams scheduled even on weekends — has made students vulnerable to mental stress. The attendant challenges — loneliness, poor cultural acclimatisation, and the perpetual fear of failure — have only exacerbated the crisis.

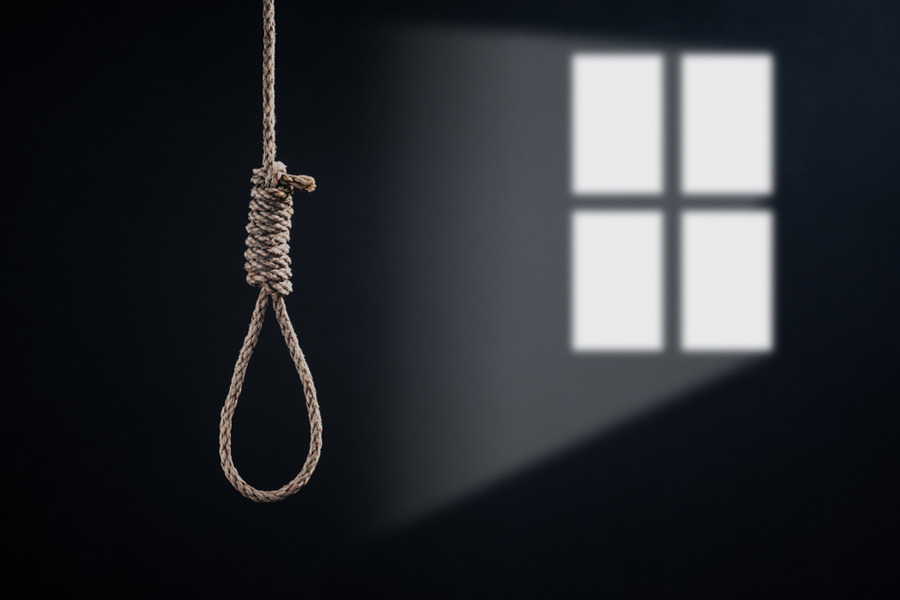

This spate of preventable deaths calls for urgent corrective measures. But the administrative laxity is shocking. In a bizarre response, the Kota administration has ordered the hostels to instal a spring device and a sensor on ceiling fans to prevent students from trying to take their own lives. Such myopic interventions intend to put the blame of such deaths on students: worse, they can subject them to surveillance and, consequently, induce additional anxiety. Incidentally, the other directives issued by the administration last year — weekly off days for students and psychological evaluations for both students and teachers — are yet to be implemented. But administrative apathy is only a part of the problem. Kota’s suicides are suggestive of deeper structural impediments: relentless pressure exerted by families and institutions to excel, shrinking employment opportunities and fierce competition. The recent string of suicides must serve as a wake-up call. Ensuring the mental well-being of students through counselling and awareness programmes must be short-term goals. But can society rid itself of the habit — malaise — of demanding excellence from young minds?