Our relationship with the material world has undergone a sea-change. Utilitarian attitudes towards consumption have been replaced by ones that are experiential and aspirational.

Commodities are increasingly seducing customers through provocative images that create an experiential ambience. They offer an elusive experience instead of merely attempting to sell a product. Let us compare two automobile advertisements from two different eras to substantiate the point. The copy of a Tata Safari ad read: “Are there… [L]ocations you’d visit that search engines can’t find? Enjoy the experience that you don’t need to ‘like’? Go places that are already in silent mode. Forget, not just timeliness. But time itself.”

The targeted consumer here is an individual, ideally a solo traveller. The ad is substantially different from the familial solidarity once expressed in the tagline of the ‘Hamara Bajaj’ campaign. The Safari ad is least concerned with fuel-efficiency, expressed memorably in such earlier taglines as ‘Kitna deti hai’ or ‘Fill it, shut it, forget it’. The Tata Safari ad does not waste time on describing product-utility barring engine-capacity and power. The focus is on selling an experience, a commodity-mediated self-indulgence. The product is thus a means to savour such an experience.

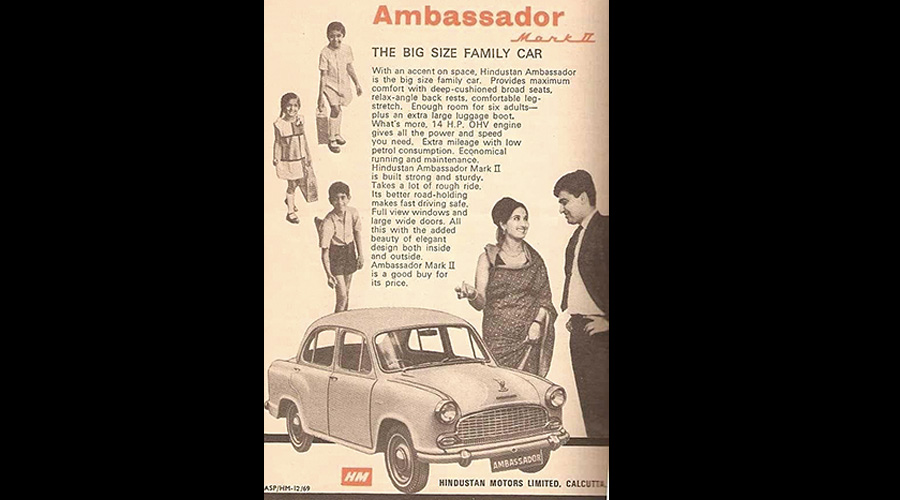

In contrast, the text-heavy Hindustan Motors ad from the pre-liberalization era tells us a different story. The ambassador ad conceives of the family as a collective unit of consumption where there is a disproportionate emphasis on utility and efficiency; the text read: “With an accent on space, Hindustan Ambassador is the big size family car. Provides maximum comfort with deep cushioned broad seats, relax-angle back seats, comfortable leg-stretch. Enough for six adults — plus an extra luggage boot. What’s more, 14 H.P. OHV engine gives all the power and speed you need. Extra mileage with low petrol consumption. Economical running and maintenance…”

The communication repetitively harps on value-for-money. The idea is to communicate that the consumer will get a lot more without over-spending. What is also discernible is that textual claims mattered more than the sophistication of imagery as the advertisements of the pre-liberalization era mostly adopted a pedagogic approach to educate the consumer about the product. For example, ads of health drinks like Horlicks and Complan preached vitality, nourishment and growth; Prestige cooker ads prioritized safety; those of Strepsils and Saridon offered instant pain relief; the ads of fairness creams and soaps promised beauty while automobile ads reiterated fuel-efficiency.

The obsession with ‘mileage’ has now been overshadowed by ‘adventurism’ accompanied by machismo. Taglines of some of the new bike ads read: ‘The all-muscle Hunk’, ‘Start the thrill’, ‘Raw power, real muscle, ripped to the core’, ‘Fear nothing’. Safe, convenient, domesticated vehicles, be it the Ambassador car or the Bajaj scooter, that could carry the burden of the entire family have given way to the consumption of flamboyance, speed and adventure.

What we are also witnessing is a major shift from use-value to sign-value. The ‘image’ of the commodity has taken precedence. Commodities are increasingly being premised on the principle of semiotics that are visually curated to trigger the aspirational-impulse.

These transformations in the consumerist landscape are demanding an annihilation of restrained consumer attitudes. Commodities were never so central to the cultural project of the masses ever before.