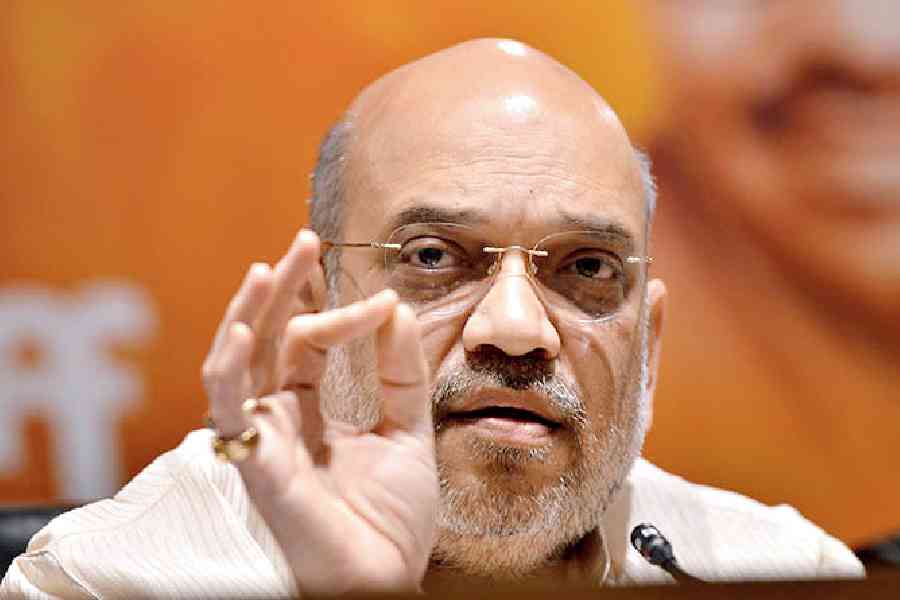

The Union home minister has stirred — at last. On his visit to Guwahati — not Imphal — Amit Shah stated that he would be visiting troubled Manipur soon — why not now? — and appealed to the warring sides to maintain peace. Mr Shah — he was busy with the Karnataka elections even as Manipur burned — has reasons to be worried. The fire that had engulfed the state on account of ethnic strife between the Meiteis and the Kukis left in its wake a trail of death, destruction and displacement. Worse, its embers continue to glow: a person reportedly died and houses were set on fire even on Wednesday. Mr Shah has received delegations from Manipur’s political representatives in recent times. But what is astonishing is that not a single leader from the Central government — the Bharatiya Janata Party is in power in both Delhi and Manipur — found time to visit the state. This delay could signal an inertia that could have an adversarial impact on a number of fronts. Already, Kuki legislators as well as civil society representatives from the state, disillusioned with the alleged partisanship of the N. Biren Singh government, have ruled out dialogue with the latter. On the other hand, several BJP legislators and their alliance partners have urged the Centre to end the suspension of military operations against Kuki insurgent groups. The fractious signals cannot be clearer. Mr Shah’s intervention should have been swifter. Manipur, like much of the Northeast, has had a long history of violence. That must not be allowed to return. It could have a spill-over effect in the region, coalescing into an inferno that India’s neighbours could be willing to stoke.

The immediate trigger of the violence had been a legal judgment that granted Meiteis the benefits of affirmative action. But the fault lines have a prehistory and the diverse manifestations of the chasm cannot be papered over. For instance, colonial law has resulted in a skewed arrangement of land rights between Meiteis and Kukis. The anxieties — real or imagined — that were triggered by the Manipur High Court’s order can be traced to the fear of the fragile, dated land rights being rearranged. At the root of Manipur’s problems is an old scar: equitable access to sparse resources. A resolution is unlikely to be immediate. It would require patient, incremental steps and a sustained engagement among all stakeholders. But does the Centre have the time or the willingness to do so?