Education has been one of the worst-hit sectors of society during the Covid pandemic. Classes have been disrupted, examinations postponed, learning interrupted, and the socialization that institutional education provides has almost disappeared, at least for the time being. Technology has provided an alternative by facilitating online classes through internet-enabled services. These internet platforms have grown rapidly during the last two years. Many pundits have declared that this mode is going to be the new normal.

Learning technologies have changed with amazing speed over the years, moving from chalkboards to white boards with markers, to television-enabled videos in the classroom, to overhead projectors and, more recently, to the computer monitor with speakers and animated presentations. The classroom has been liberated from the dusty notebooks of the instructor, and the new audio-visual techniques have brought several additional dimensions to the learning experience. It has also made life potentially a lot easier for the instructor. Writing on the board and deriving complicated formulae have become things of the past. One can bring into the classroom a lecture by an internationally renowned scholar through just a click of the electronic mouse. It is left to the teachers

to master the new devices and make the classroom more attractive. It does not matter what the subject is or the level at which the discussion is carried on. Whether it is playschool or kindergarten or graduate seminars, philosophy or physics, there is something embedded in the technology that enhances learning.

Emerging technologies mean new business opportunities too. There are two kinds of revenue models. There is money to be earned by supplying new equipment to each and every classroom at all levels of education: the software programmes and applications are regularly updated and improved, computers gather faster processing powers, projectors become more versatile, and even classroom opinion polls can now be taken quickly and anonymously. Virtual libraries have become well-stocked and are easily accessible. There is now an impressive choice before the teacher to mix and match learning technologies to suit the subject and learning goals. The other area that has opened up to business opportunities is the possibility of having renowned teachers from the best institutions record their lectures (often a set of lectures constituting a full course), and then have students access them through paid registration. There is an added advantage over and above the universal access; that is the asynchronous nature of the resource. One can listen to it at night after a hard day’s work, according to one’s own convenience. Before Covid, the classroom was the central place for learning, the instruments were liberating, and anyone looking for supplements could always fall back on the online courses for additional stimulation. Online learning was the icing on the technological cake.

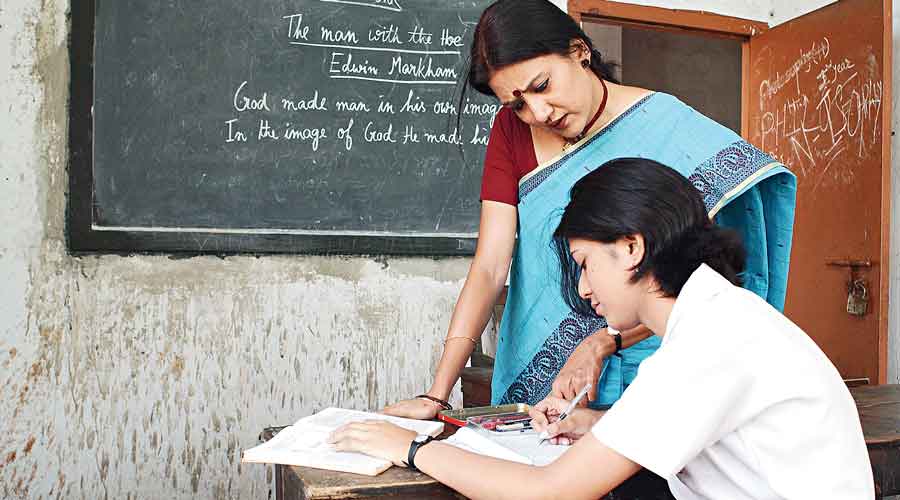

How have all these changes affected the pleasures of teaching? Teaching in a classroom is equivalent to giving a live performance. There are some differences: there are no prompters and there is no set script like that in a play or a film. The classroom script is dynamic as questions are asked and new issues posed by alert and intelligent students. Good teachers change their styles and content to suit the atmosphere of the class. Even classroom mischief has its own use. It provides a mild distraction and minor entertainment. Yet it is similar to theatre in an important sense: the audience is live. More often than not, the perceptive teacher can make out from the expressions of the students how the ‘script’ is being received. One can make out if one has really performed well and established a rapport with students just by those extra two seconds of stillness after a class is dismissed. A good teacher notes this with a great deal of satisfaction.

When I was first asked to take online classes for corporate executives — a couple of decades ago — by sitting in front of a camera and a computer monitor, I felt what many stage-actors must have felt in front of a movie camera for the first time. It was no fun. One knew one could reach many more students than the number that fitted into a standard classroom or even in a large auditorium on campus. However, the faces were missing, and the body language invisible. The number of questions dropped too. It was more like cinema: a recording done so that students could view it later in their free time. In short, like cinema, it was asynchronous. However, it is still not quite cinema or even television, since retakes are not possible and the script remains dynamic. When I began teaching in this mode, I was uncomfortable in the initial weeks but gradually adapted. My passion for ‘performing’ dropped significantly and I rationalized my reaction by noting that I was teaching practicing managers in the evening, and that the course was an extra dose of learning for them. It was not basic knowledge being imparted.

The pandemic brought a closure to the offline, in-class performance not only for the grown-ups but also for the tiny-tots and children. This is where things have got really messy. One cannot see the students; one is not even sure if a particular student is attending or not; discussions and debates have become infrequent and time-consuming with eerily invisible participants. It is well-known that with the advent of cable television and the internet, our attention spans have fallen drastically. These classes do not allow the passion of the teacher to be shared with the students, the dynamism of the script is restricted, even the filmic impact of cinema being larger than life is lost since the viewings are on small screens, usually much smaller than even a television set. Hence the learning experience is much inferior to an offline, in-class session.

I have heard famous professors in person addressing a seminar, and the same person ‘performing’ in an online lecture. The vibrations are much lower in the latter. Online courses serve a purpose. One can access a course, which one may not have had the opportunity to enrol in at university. That, however, is not the staple learning that constitutes formal education. It is like a snack; at best supplementary.

I believe in the flavours of real classrooms. If the online mode becomes the new normal, something will be lost in the enjoyment of teaching and learning, something that I have valued from both sides of the teacher’s lectern. Although enabling in many ways, new technologies always have a dehumanizing aspect: we win some, we lose some. I can merely be a sad onlooker as the second best is being elevated to the winner’s podium, perhaps inexorably. I am glad I have finished my last class while it was still fun.

(Anup Sinha is former professor of Economics, IIM Calcutta Past practice)