On February 28, an open letter was released by PEN International, a body of writers from over 120 countries. It had over a thousand signatories, among whom were many Nobel laureates, distinguished writers, legendary artists, and prominent journalists.

It reads: “To our friends and colleagues in Ukraine, We, writers around the world, are appalled by the violence unleashed by Russian forces against Ukraine and urgently call for an end to the bloodshed. We stand united in condemnation of a senseless war, waged by President Putin’s refusal to accept the rights of Ukraine’s people to debate their future allegiance and history without Moscow’s interference. We stand united in support of writers, journalists, artists, and all the people of Ukraine, who are living through their darkest hours. We stand by you and feel your pain. All individuals have a right to peace, free expression, and free assembly. Putin’s war is an attack on democracy and freedom not just in Ukraine, but around the world. We stand united in calling for peace and for an end to the propaganda that is fuelling the violence. There can be no free and safe Europe without a free and independent Ukraine. Peace must prevail.”

The letter received a touching response from Ukrainian writers and artists. They said, “We are still fighting with Russia and the biggest part of the country sleeps in bomb shelters. Some of our authors were forced to leave their homes because Russian missiles have ruined their cities and villages.” Several writers are fighting the Russian occupation of Ukraine with arms in hand. Just two days before, the Russian forces had burnt down the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum, which housed, among other artefacts, the precious works of the folk artist, Maria Prymachenko.

I have met many of them in the recent past in Ukraine and some in Pune, India. The ones who came to India had come to pay homage to Kasturba Gandhi during the 150th year of Mahatma Gandhi’s birth. The ones I met in Ukraine had assembled at Lviv (not to be mistaken with Kyiv). Lviv is located in the western part of Ukraine, about 70 kilometres from the border of Poland. Situated on the banks of the river, Poltva, it has a history of human habitation for over 35,000 years as well as a 6,000-year history of agriculture. A century ago, the people of Lviv decided to cover the river flowing through their city and build upon it. For instance, the Freedom Square in the city is now above the river. The built-in water channels worked like a secret hiding place for the citizens during an emergency. During the Second World War, thousands of Jews had taken shelter in the underground tunnels. It is estimated that out of the 1,60,000 who used the river as an escape route, barely 2,000 survived the Holocaust. Lviv and Ukraine have suffered so many aggressions that the life in bunkers has become a part of their folklore.

Struggle for selfhood is not new for the Ukrainians. What is new is the strange international context of the current assault on this sovereign, democratic country. Vladimir Putin of 2022 neither represents nor continues any of the pro-proletariat legacies of Vladimir Lenin or of socialism, which, in the 20th century, endeared the USSR to African and Asian peoples aspiring for self-rule. The United States of America of 2022, which was, not too long ago, rocked by the Black Lives Matter movement, has no noticeable love left for the ideas of democracy that were espoused by Thomas Jefferson or Abraham Lincoln. In Europe, Britain and the European Union together have reduced the dream of a multi-lingual, multi-cultural and conflict-free Europe to an empty shell. Besides, the international institutions that evolved during the second half of the twentieth century are enfeebled beyond repair and the international community of nations has not been able to give rise to an effective mechanism that can keep in check the rising ambitions of superpowers. The enormous imbalance of trade, technological prowess, military might and command of natural resources between the superpowers and the countries struggling to safeguard their existence has created a grammar of geopolitics that is almost absurd. It appears to have departed from the idea of a ‘community of nations’ associated with the modern world and has probably entered the nihilistic abyss surrounding Nietzsche’s concept of Superman, or is mired in a topology of Orwellian Animal Farms.

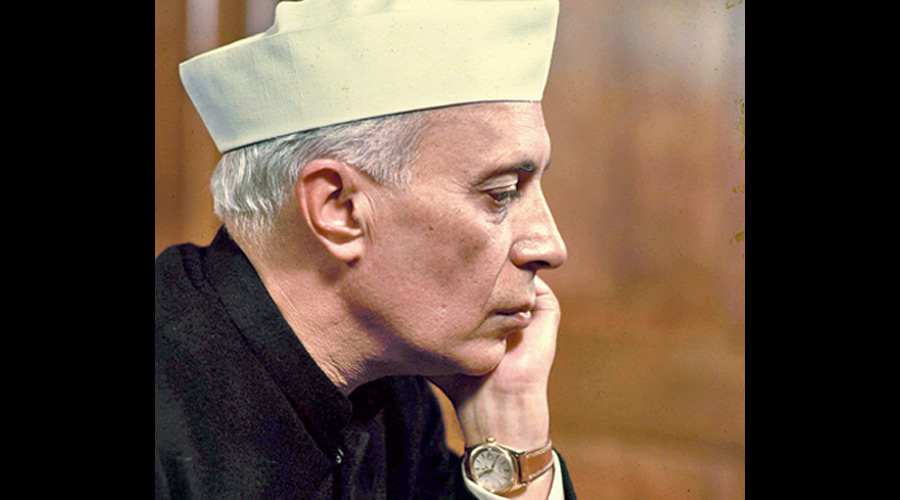

With the solitary exception of Jhumpa Lahiri, no Indian writer or artist was among the signatories. That was not because millions in India have not been grieving for the fate of Ukraine, but because the PEN movement in India has remained insufficiently rooted. No Indian socialist has denounced the Russian aggression. That is not because Indians do not understand socialism; it is rather because Indian socialists do not have a full understanding of how far Russia has moved away from it. Similarly, the political class, irrespective of parties, has not spoken out loudly enough condemning the violation of the sovereignty of a new democracy. That is because the idea of democracy has suffered a serious setback in India itself. Today, India stands in a splendid international isolation. That is neither because it is adhering to Jawaharlal Nehru’s policy of non-alignment nor because it is following its geopolitical interests in an astute manner. Had that been so, it would be a striking paradox for a regime that spends maximum energy tarnishing Nehru’s name and legacy. Had the regime thought through the geopolitical interests of the country, it would not have worked overtime to ruin relationships with all our neighbours by methodically generating social discord within the country. India finds itself isolated because the country has lost a sense of its exact place in the community of nations which is that of the most populous democracy. It seems to have pushed itself in isolation because it has forgotten that Nehru’s non-alignment in external affairs was organically linked to his idea of a non-partisan secularism in home affairs and, therefore, rarely did either of them sound hollow in his case. Ultimately, championing democracy requires a moral courage, the kind that the Ukrainian writers willing to die for it are showing. Championing non-alignment requires tolerance irrespective of race, religion or ethnicity. For want of both, what one can achieve is a self-diminishing isolation and a pitiable self-glorification.

G.N. Devy is Chair, The People’s Linguistic Survey of India