Professor Lord Bhikhu Parekh is a political theorist and, as a member of the House of Lords, is, along with Professor Lord Meghnad Desai (both from the Labour Party), one of that rarest of rare beings — a Gujarati settled in that green and pleasant land not to run a flourishing business but to teach and write and enrich the world of Britain’s Life Peers with the intellectual leaven of Baroda.

In an unusual essay that he wrote in 1994 titled “An Indian View of Friendship”, Professor Parekh speaks of sauhrda or good-heartedness as being at friendship’s core, with three ingredients: ananda (delight), sahaya (help) and abhaya (fearlessness). The first of these confers on friends “fun, merry-making, playfulness, agreeable and amusing conversation, escapades and disregard of social conventions”. And he gives as an epic example of this kind of friendship, the tie in the Mahabharata between Krishna and Arjuna. The second is marked, he says, by “care for each other… un-calculating sacrifices of time, energy, money, even life” and gives the example from the Ramayana of Sugriva and Rama. Of the third ingredient, he says it enables friends to “be at ease and… know no fear or anxiety’ in each other’s company”. And he lets the story of Krishna and Sudama speak for itself — the Kshatriya and the Brahmin overcoming the divides of caste and class to maintain a relationship that lasts seamlessly through unequal statuses because their hearts had “become bonded”.

Re-reading this riveting text after a decade, I could not but ask myself what the condition of friendship is in today’s India, verily an oceanic theme. And I thought I would, in a rumination, catch a cupped handful of that brine — Friends and Friendship in India: 2023.

What would, say, five great friendships in India over the last seventy-five years be? And, is the nature of friendship in India changing?

I can straightaway hear an objection: are friendships to be noted only among the ‘great’? Are there not great and true friendships to be found among the non-famous? I grant the merit of the objection but seek exculpation in the clarification that what I have in mind is not friendship among the great but great friendships with what may be called the Parekh paradigms of ananda, sahaya and abhaya. And with that, I venture to identify five that strike me as notable.

Mahadevi Varma, queen of the Chhayavad school of a rather obscure Hindi poetry, lived reclusively in Allahabad. A khadi-wearing, vegetarian introvert, she was not a little irritated one day by the persistence of a Chinese vendor of silks at her door. Telling him in her simplest Hindi to make himself scarce, she used the word, ‘Bhai’. The vendor was touched. “You called me Bhai… You are my sister… the one I have lost…” So saying, he kept coming to her house every other day not to sell anything but to tell her his life-story. The two bonded. Mahadevi tells the story of this friendship in her gripping story, “Mera Chini Bhai”. Pure ananda defined this friendship, which ended, alas, on a sad note.

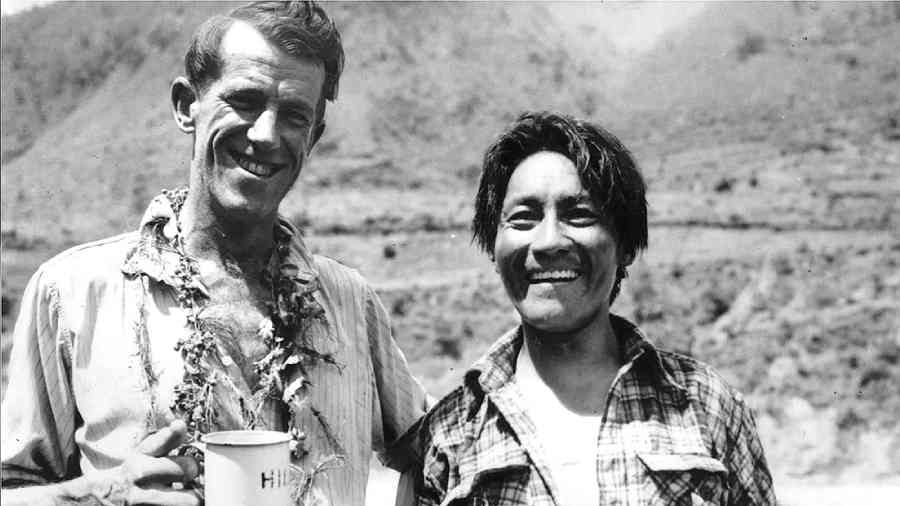

Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary may not be described as friends. They might not have used that term to describe themselves either. But they were a two-man team that can never be seen apart from each other. The question that could divide their partnership, their twindom, was and has remained unanswered is: ‘Who got the Everest’s summit first’? Neither satisfied the world’s competitive curiosity. Not in memoirs, not in press conferences. Neither said anything that could feed the mill of gossip-greed. ‘And then we were there’ is about how they let the world see their conjoint triumph. Their ascent of Everest was about training and teamwork triumphing through the grace of good weather and good luck. Their descent into the level ground of babbling busybodies and their warm mutuality on that stony surface were about respect, civility and plain decency confounding cynics with bad bio-chemistries and worse. This was the friendship of sahaya.

‘Stormy petrel’ is a phrase that may be said to have been coined for the socialist rebel, Ram Manohar Lohia. When he died in 1967, I remember telling my sister-in-law, Indu Gandhi, a teacher of Philosophy at Delhi University: “Bhabhi, such a pity there is no one like family for him with whom one may condole.” “Of course there is,” she corrected me, “Roma Mitra”. That was the first time I heard of this remarkable friend of Lohia’s, also a teacher in Delhi University, with whom he maintained an intimate and open friendship for years. Both words are important — intimate and open. Ram Manohar and Roma shared in common that which only they could define but also intellectual trust, ideological thought-partnering, and utter frankness. His letters to her, published but not fully absorbed by our self-centred times, speak of abhaya in every sense of the term.

Beyond these three categories of friendship are some that are indefinable. Dr V. Shanta who, with Dr S. Krishnamurthi, ran the Adyar Cancer Institute in Chennai, gives us an amazing example of friendship in the cause of professional dedication. The two oncologists were made to work together. They gave their time, their energy, their lives to the cause in a mutuality that was taken by everyone for granted. Countless beneficiaries of their medical attention thank them for having been there for them. Collaboration is not an adequate phrase to describe what they attempted and achieved together, redefining friendship.

No two persons could be more different from each other as Naresh Kumar, the Calcutta-based tennis player and captain of the India Davis Cup team from 1989 to 1993, and Ramanathan Krishnan, twice a semi-finalist at Wimbledon in 1960 and 1961, and counted among the world’s leading players in the 1950s and the 1960s. Naresh, a denizen of modern megapolises, and Krishnan, a resident of orthodox Mylapore in Madras, were closer than two scoops of the same ice cream in one cup or two idlis from the same deck of steam hollows. Their lives were a game of ‘singles’ played with grace and verve, a silken filament linking them over the net of life.

There is trust in such friendships, there is faith. There is frankness, there is also another thing so important to friendship — detachment. There is no grasping of the other’s presence, no claim to the other’s exclusive attention. There is peace. That relationship does not know what a transaction means, let alone what a contract means.

That relationship is now becoming rare.

So is the true friend, the dost, a relic of the past?

No, certainly not. Every reader of this column will cite several friends that she or he is privileged to have, as I do.

But we live in times that abound not in friends as much as in another category — allies, partners, collaborators, accomplices, fellow-conspirators, cronies. And (to descend to slang) sidekicks. Appropriately, the Hindi word, chamcha, has made its way to the Oxford English Dictionary which describes it as “a person who tries too hard to please somebody, especially somebody who is important”. The rise of the ‘important person’ in society as distinct from ‘the great person’ has generated a new order of human relationships in which the protection and the preservation of importance and its ‘trickle-down’ effect on the important person’s ‘circle’ overwhelm relationships. The phrases, ‘good friends’ and ‘close friends’, are now overtaken by ‘thick friends’, the two ‘thicks’ living in a spectrum of mutual protection, mutual dependence, and mutual vindication.

It is not as if these types did not exist in the past. They did, they always have. The regret is just this that their surface density has increased in our times, rather alarmingly. The Chhayavad poet, Nirala, anticipated this decades ago: “sneh nirjhar bah gaya hai/ ret jyun tan rah gaya hai (All love has cascaded away/ We are now just hulks of sand and clay)”.