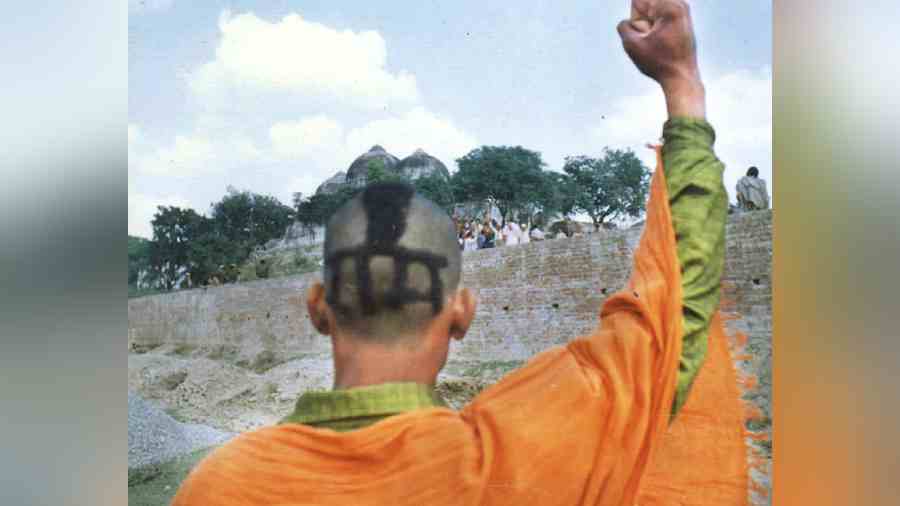

Three decades ago, it seemed to many Indians, but particularly an anguished commentariat, that December 6 would acquire a special significance as either a Black Day or Shaurya Divas. Despite its overwhelming contemporary importance as the anniversary of the demolition of the 16th century Mughal shrine in Ayodhya — better known to some as the Babri Masjid and to others as the ‘disputed structure’ — the day hasn’t yet entered the political calendar as a moment of commemoration.

This is unlikely to change. Although the movement for the construction of the Ram Janmabhoomi temple in Ayodhya is certain to be viewed as an extraordinarily important phenomenon in the history of post-Independence India, the special significance of December 6, 1992 is likely to be underplayed. In terms of the commemorative calendar, the inauguration of the ‘bhavya mandir’ by either the head of State or the prime minister next year is likely to be projected for the future as Hindu Resurgence Day.

It could so easily have been otherwise. Those who recall that turbulent December in 1992 when large tracts of India were affected by communal rioting would testify that the political temperature had risen high enough for pundits to suggest that the death anniversary of Bhimrao Ambedkar would coincide with the Republic going into self-destruct mode.

The demolition in Ayodhya generated three very distinct responses.

The loudest — but politically the most inconsequential — noises emanated from the liberal intelligentsia. Heard in all relevant sections of the globe, but particularly the Anglosphere, theirs was a cry of anguish, coupled with demands for political retribution. Through the tearful eyes of the activist media that had assembled in Ayodhya to document the menace of an India that had apparently refused to grow out of a medieval mindset, the demolition was equated with the destruction of a composite culture and the end of secularism as known since the days of Jawaharlal Nehru. The next morning saw angry and agonised secularists demonstrate before the Bharatiya Janata Party headquarters on Ashoka Road in Delhi carrying placards that included the slogan, ‘Sharm se kahon hum Hindu hain’ — an inversion of Swami Vivekananda’s proud-to-be-a-Hindu assertion that Hindu nationalists had made their own. The blame for the mob action that had led to the demolition and the construction of a makeshift temple was laid squarely at the door of Hindu leaders who were painted as enemies of the Constitution.

Outrage was coupled with demands for retribution. The ‘progressive’ mindset that had gloated over the arrest of innocuous Sanskrit teachers with Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh connections during Indira Gandhi’s Emergency between 1975 and 1977 now demanded a purge of saffron sympathisers and activists from all educational institutions and the media. The RSS, predictably, was banned as a knee-jerk reaction of a disoriented government. Also knee-jerk was the public commitment by the then prime minister, P.V. Narasimha Rao, to rebuild the mosque where it had stood, a commitment that generated a fierce Hindu backlash and was quietly and unceremoniously shelved thereafter. This demand for what became known as ‘hard secularism’ or ‘secular fundamentalism’ was popular in Left circles. But it also contributed to an incoherent response from the Congress government. The Rao government veered wildly between ‘hard secularism’ and trying to be accommodative to Hindu interests. Particularly comic was its attempt to rally all those godmen who, for some reason or other, had not identified with the Vishwa Hindu Parishad.

The Muslim response, too, veered between two extremes. The members of the community attached to the Congress were incensed that the Centre had failed to protect the structure. This led to the Congress losing Muslim support in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar and the emergence of the likes of Mulayam Singh Yadav and Lalu Prasad as ‘Muslim’ leaders. The sense of Muslim despondency did not lead to any surge in the popularity of Muslim parties, such as the one headed by the Owaisi family of Hyderabad. However, ominously and partly because of the communal riots in cities such as Mumbai, a section of Muslims veered towards retributive terrorism. Their biggest success was the series of 12 devastating explosions in March 1993 that killed more than 250 people in Mumbai. The terrorist cell was subsequently identified as taking the help of both Pakistan and the criminal underworld of Mumbai. Overall, it can be said that the Babri demolition radicalised a section of Muslims and triggered the rise of Muslim terrorism (outside Jammu and Kashmir), a problem that, despite its containment after 2014, persists.

There was probably no composite Hindu response to the Ayodhya demolition. Opinion polls of the time suggested a sense of tacit approval coupled with full support for the building of a Ram temple. However, what worried the RSS and the BJP leaders most was that extremist impulses generated by the demolition would secure an upper hand and veer the movement into a more directly confrontationist approach. By 1994, a conscious decision had been taken to avoid confrontation and quietly consolidate the gains made by the agitation. A decision was also taken to fight the court cases with seriousness and simultaneously work towards securing a pro-Hindu government at the Centre. VHP leaders such as Ashok Singhal sought to disengage the temple movement from the BJP, but this was never entirely successful.

I n the common perception, the temple movement came to be identified with those impulses in society that equated a strong India with a country that was proudly and unashamedly Hindu in its orientation. The Atal Bihari Vajpayee government was initially seen as pursuing such an agenda. However, when coalition imperatives forced it to beat the secular drum, it dampened the mood of those who helped propel it to power in 1998. The Bharatiya Janata Party’s 2004 defeat can largely be attributed to the despondency of its committed Hindu core. It was this offshoot of the Ayodhya movement that was responsible for forcing the RSS leadership to anoint Narendra Modi as the BJP’s face for 2014.

The advent of Modi has had a psychological impact on the Hinduness generated by the Ayodhya movement. Regardless of the political fortunes of the BJP, there is now a Hindu mood that all governments have to factor. That has been the real contribution of a process that was galvanised three decades ago.