The trade union leader, A.K. Roy, who died recently, represented an era of Indian politics that is now absolutely and comprehensively in the past. He served three terms as an MP from Dhanbad, elected as an independent, without formal party affiliation, and with his campaigns funded through thousands of small donations by mine workers and middle-class sympathizers. Roy never married, and, when in Dhanbad, lived like his constituents, in a thatched hut with no electricity. In his character and lifestyle, he was worlds removed from the fat cats who now sit in the Indian Parliament, funded by their crony capitalists.

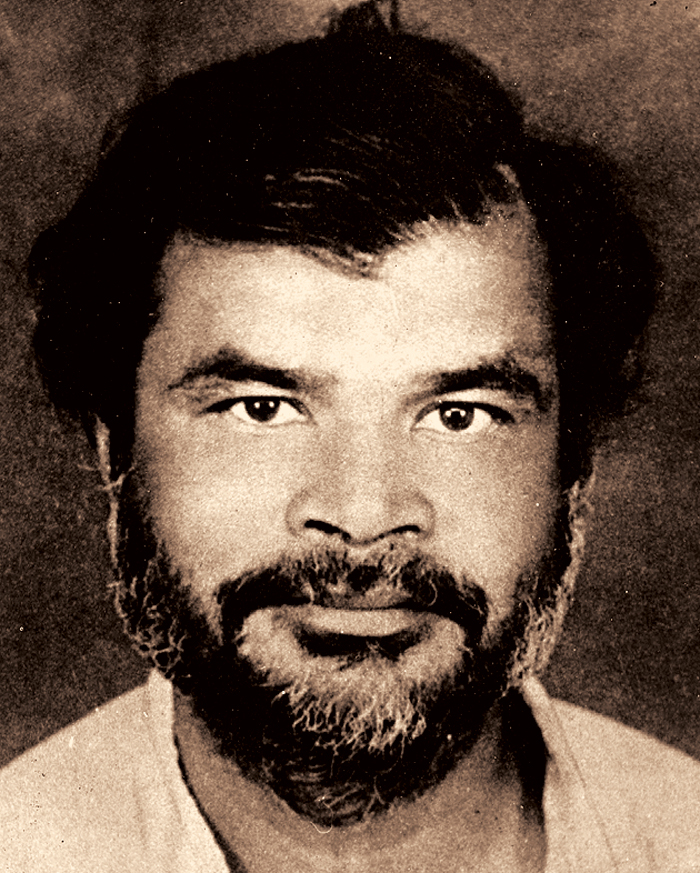

Reading of Roy’s death brought back memories of the one occasion when I almost met him. In the year 1981, I was a student volunteer at a conference on the environmental and social impacts of unregulated mining. I was sent by the organizers to invite Roy. I went as instructed to his MP’s flat, a tiny two-room place in Vithalbhai Patel House, far removed from the Lutyens’ bungalows that the MPs of today covet and occupy. I knocked, and when no one answered, knocked loudly and more insistently. The door was opened by a tall man, in a kurta pyjama, rubbing his eyes. It was not Roy, yet I recognized him at once. It was Shankar Guha Niyogi, the legendary workers’ leader from Chhattisgarh. He told me, very politely, that Roy was out, but he would convey my message. His courtesy shamed me even more. This man desperately needed the few minutes of sleep he could get, and I had denied him even that. I remain guilty still.

I remembered Guha Niyogi when I heard of Roy’s passing, and I remembered him again when reading, in English translation, the memoirs of the Bengali writer, Manoranjan Byapari. Byapari’s first impressions of Guha Niyogi were much like mine, except that he saw him not in our grand imperial capital but in a village in Central India. At a meeting of the Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha, Byapari witnessed “a tall fair man, with bright eyes, clad in khadi pajama-kurta, seated with many others on the grass. Though amongst many, he did not blend in with the crowd. The power of his personality was evident in his smiling, clear face. He stood tall, a full head and shoulders above others — a head that had not learnt to bow before injustice. A head that money could not buy.”

Later, Byapari went to Guha Niyogi’s home. “To my surprise, I found his was as poor a residence as any found in the labourers’ slums. One single room with two verandahs on either side. Mud walls with burnt khaprel for the roof... When I arrived there, Shankar Guha Neogi, with his monthly allowance of seven hundred and fifty rupees, was sitting happily with his family of wife, two daughters and a son, on an unsteady chowki, sipping tea.”

Shankar Guha Niyogi began as a Marxist, but over the years came ever closer to Gandhi. Byapari thus renders what Guha Niyogi told him about the philosophical and practical synthesis he had arrived at: “Jai Prakash Narayan had attempted a constructive movement, but that failed. The Naxalites attempted a destructive movement, but that too has failed. I’ve therefore come to the conclusion that a certain harmony needs to be brought about between construction and destruction. Hence our slogan, ‘Construct to destroy, and destroy to construct’. It is with this in mind that we have attempted, through our organization, to build here hospitals, small schools, workshops, cooperatives and cultural societies. Through these efforts we have tried to tell the people what the new society that we have in mind could be like. The other thing that we try to do here is to avail the maximum benefits from the avenues allowed to us by democracy — through meetings, rallies, demonstrations, memorandums, deputations.”

Guha Niyogi told his visitor that, in the narrow, economistic approach of the trade unions led by the CPI and the CPI(M), “there is no constructive thought given to the life that the labourer lives outside the factory walls. We have done that. We have tried to ascertain what a man or woman needs to make life healthy, progressive and beautiful.”

Explaining the distinctiveness of the CMM, Guha Niyogi continued: “We have demanded higher wages for the labourers. Higher wages have been achieved. But that wage has gone into liquor. So we had to build up an anti-liquor movement. Now that is not an expected part of the trade union’s itinerary... We have therefore had to turn to Gandhi for inspiration. We have drawn from the welfare theories of all isms — Marxism, Gandhism, Lohiaism, Ambedkarism. We have studied them, borrowed from them, and adapted them to suit our needs here.”

Many years ago, the writer, Rajni Bakshi, published a fine tribute to Shankar Guha Niyogi (available `online`). She wrote there of the State repression he had faced; a year in jail during the Emergency, false cases continually slapped on him by the government; this persecution culminating in his murder in September 1991 by goons hired by industrialists, with the police and the politicians looking the other way. He was forty-eight at the time.

Rajni Bakshi reminds us that Guha Niyogi was, like Gandhi, a precocious environmentalist. It was the pollution of free-flowing rivers by mines and factories that first alerted him to the problem. She translates an article he wrote in Hindi on how to blend social justice with environmental sustainability. Niyogi called here for a democratization of forest management, and for tough action against those who polluted the atmosphere and the waters. The “causes of environmental destruction will have to be analysed”, he wrote. “Consciousness on environmental issues must be developed at the national level in a comprehensive manner,” he continued. “The more conscious activists of the union”, he said, “will try to build an understanding of the environmental movement in India and the world. They will also work to build fraternal links with the movement and prepare activists and general members to represent the union in events and activities of the movement.”

The article then went on to prescribe specific policies to resolve specific problems. Thus, Guha Niyogi wrote, about the forests: “When the people are able to feel and know that the jungle is truly theirs, from that day every one of them — even the little children -— will keep a watchful eye and protect the forests. Then the forest thieves will be stopped and the ills created by useless and irresponsible officials will be undone. When the forest becomes a means of preserving collective well-being then all its dwellers will act against every stroke of any axe used to cut trees illegally. Such protection of community interest will in turn secure the national interest. This will not only protect the environment but also guarantee the future of humanity.”

Niyogi ended his article with these resonant sentences, even more relevant now than when they were first written: “The truth is that we will have to protect our earth and our planet. The trees, plants, clean drinking water, clean air, birds and animals and human beings — together all of us form part of this world. Through sensitive ideas and flexible programmes we will have to maintain a balance in nature and in science and this can be done on the basis of the development of people’s consciousness.”

In his own memoirs, Manoranjan Byapari writes: “Neogiji could not be pigeon-holed into any single ideology. That would be a difficult — no, an impossible endeavour. He was beyond all isms. He was a great humanist. The only person in history I can compare him with is Gautam Buddha who left the palace to come and stand with the poor and the suffering.”

A young adivasi leader named Ravi Taylor explained to Byapari the causes and consequence of Niyogi’s death: “As long as he had lived, he had kept alive in the minds of the tribals a belief in the constitutional order. It is for this reason that many had called Neogi the Gandhi of Chattisgarh. And it is for this reason that he was shot to death. He had not harmed anybody. Yet he was killed. And his murderers were not punished. The justified demands of the labourers were silenced by the guns of the police and industrialist mafia. Now whom were the labourers to go to with their grievances? A colossal darkness had descended after Neogiji’s death. Human beings need a support. With Neogiji’s murder, that support of the tribals had been wiped away, leaving a yawning hole.”

That hole was sought to be filled by the Naxalites, whose closed minds and murderous methods provoked savage counter-violence by the police and the paramilitary and have pushed the adivasis to the brink.

In terms of their integrity and courage, A.K. Roy and Shankar Guha Niyogi were cut from the same cloth (although Guha Niyogi was certainly the more original thinker). There can never be another A.K. Roy because electoral bonds have ensured that an independent, non-party candidate who wishes to represent peasants and workers cannot now sit in Parliament. And — at least in the short-term — there cannot be another Guha Niyogi either, for the State is even more repressive and even less tolerant of non-violent dissent than it was in his day. In these dark times, it is obligatory for those Indians who knew or knew of them to keep their memory alive.