The markers of assessing Indian democracy are, evidently, undergoing a transformation. Speaking at the United Nations General Assembly, the prime minister — typically — cited his own example as proof of the robust nature of India’s democracy. But Narendra Modi is not the only politician from an ordinary background to have gone on to occupy the prime ministerial chair. From Lal Bahadur Shastri to H.D. Deve Gowda, Indian democracy has elevated many a leader with humble roots to the highest echelons of power. Neither is Mr Modi going to be the last of such inspiring examples as long as democracy retains its original, heartening, Indian characteristics.

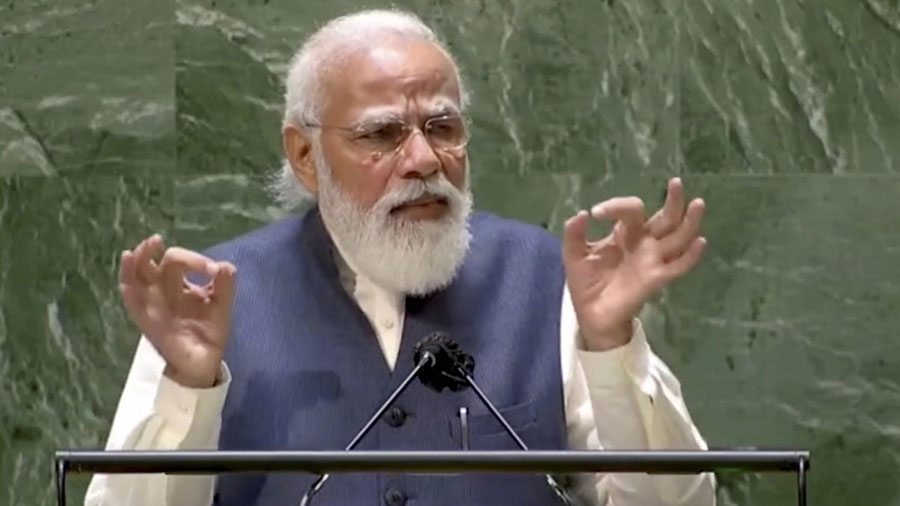

But will it? That is the principal question. There is mounting concern, in India and around the world, that the democracy project in the country is experiencing unprecedented strain under Mr Modi’s watch. The evidence is indisputable. There has been an unambiguous crackdown on dissenters; institutions that are tasked with protecting the democratic edifice are allegedly being hollowed out from within; then, there is the predation by an overarching Centre on the ambit of the states, weakening India’s federal set-up; civil liberty as well as pluralism — the cherished dream of the founding fathers of the nation — is being threatened. This deterioration has caught the attention of the international fraternity. India, with Mr Modi’s government at the helm, has performed poorly on credible indexes on press freedom and religious tolerance while, in its annual report, the V-Dem Institute described India as an ‘electoral autocracy’. What must be mentioned is that both the president and the vice-president of the United States of America reiterated the importance of democracies upholding the ethos of democracy and the assurances that come with it. Could it be that the two leaders were making an oblique reference to India’s performance under Mr Modi in this context? When it came to his turn to speak, the prime minister, expectedly, waxed eloquent on India’s democratic traits, warning — many Indians would find this ironic — against the threats posed by “regressive thinking” and an ‘anti-scientific temper’. It is clear that the prime minister’s homilies on the state of Indian democracy are being met with scepticism. The possibility that Mr Modi may no longer be the face of a vibrant, functional, durable democratic polity is gaining momentum.