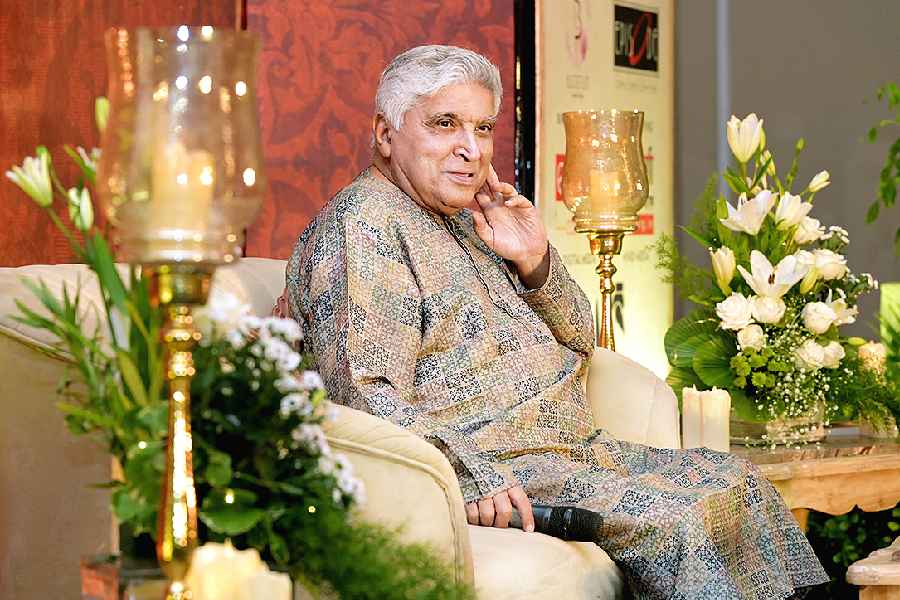

Poetry has always been a bit awkward, its relationship with the political leadership often more or less uneasy, depending on the time and place. Upon being awarded an honorary degree by the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, Javed Akhtar spoke of the nature of poetry, its combination of awareness and submergence, passion and craft. In honouring the art, he asked whether it was a coincidence that fascist ideologies have not produced a single major poet. The question was rhetorical, yet coming after Mr Akhtar’s description of the destructive paradoxes that inform the post-truth era, it was also more than that. It is undeniable that some of the best-known poets and writers of the West have been known for their support of, or affinity with, fascist ideology — Ezra Pound, for instance, or Knut Hamsun. Even W.B. Yeats is not free of controversy because of his association with right-wing and fascist groups. If love, beauty, transience, elation, the untranslatable being of art — all shimmer through the poetry, in what ways does fascist ideology negate it?

Can it kill creativity? Poetry — literature — disturbs and unsettles its readers; it is always ready to upset the status quo. In its sublimity as in its capacity to wound — from the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel to the sculpture of the Dying Slave — art is far from comfy. Plato would have banished poets from his ideal republic, or so he said in his theory, but banishment, self-exile, persecution, suppression and being silenced have truly been the lot of many poets, writers and artists. Salman Rushdie and M.F. Husain loom large on this list. Sometimes their sin is to fall afoul of whichever powerful regime is in place, and sometimes it is simply that they are artists. Even without a fascist around, artists often walk the razor’s edge, concealing criticism and derision within, for example, the many voices of a stage-play. Lear’s Fool always runs the risk of being silenced.

That might offer a way to approach Mr Akhtar’s rhetorical question. Not fascist values alone, but any form of autocratic or totalitarian politics, whether born of a popular movement, an ideology, or just the power of a dictatorial personality, tends to silence, and thus kill off, not just the opposition but the independent, transgressive creations of art too. Fear and hatred are not fertile grounds for creativity. The ideology may no longer be exactly the same as that in 1930s’ or 1940s’ Europe; so labels, too, may be differently applied. Mr Akhtar’s question was placed in a precisely detailed context of today’s India, underlining the tragic barrenness produced by regimentation and repression. Yet when he spoke of the writer’s right to turn the pen into a sword against evil, it was more than a rhetorical solution. Poetry speaks of love, peace and justice especially because repressive forces try to silence it. Major poets are produced in many different ways.