Thai authorities had registered a case in April against an attempt by private individuals to set up a floating house within the Andaman Sea. The Thai press reported officials saying that the activity is part of a cryptocurrency conspiracy to establish an “independent nation”. This is potentially the first ever case on state-making and the United Nations Convention on the law of the Sea.

The seasteading project, as this venture is called, promotes living free of any nation’s laws. The Seasteading Institute promotes the creation of “floating ocean cities” as a “revolutionary solution” to some of the world’s most pressing problems such as rising sea levels, overpopulation and poor governance by “reimagining civilization”. Effectively, the seasteading project sits between the UNCLOS, 1982 and domestic law. While sea-level rise is a real problem, is the establishment of such “floating ocean cities” legal under domestic and international law? The UNCLOS Article 60 gives the right to build “artificial islands, installations and structures” in exclusive economic zones to the coastal states alone. Under the UNCLOS, coastal states have sovereignty till 12 nautical miles into sea adjacent to their coasts, called territorial sea. Coastal states are further entitled to maritime zones beyond their territorial seas, such as a contiguous zone and an exclusive economic zone. The seasteading project claims to build its enterprise beyond territorial seas of the states.

Two legal issues emerge. First, what is the legal status of these “floating ocean cities” under the UNCLOS? Notably, the UNCLOS speaks of “artificial islands, installations and structures” without defining them. Nonetheless, “artificial island” was discussed in the South China Sea arbitration case in 2016. Before the tribunal, the Philippines rejected China’s “island construction” and the “installation of small artificial structures” manned by “government personnel sustained entirely with external resources” to convert such “features into fully entitled islands.” Second, under Articles 56(1)B and 60 of the UNCLOS, only a state, not an individual, is allowed “the establishment and use of artificial islands, installations and structures”.

As the first modern implementation of the seasteading project, Chad Elwartowski, an American bitcoin trader, and his partner, Supranee Thepdet, have recently built a small platform. They claim that their sea-flat lies beyond 12 NM, beyond Thailand’s territorial sea. Thailand disagrees. The Royal Thai Navy’s police complaint under Thai criminal law alleges that the artificial structure was within Thailand’s territorial waters. The Thai naturally see this construction as affecting their national security. The breach of Section 119 of the Thai Criminal Code is punishable by death or life imprisonment.

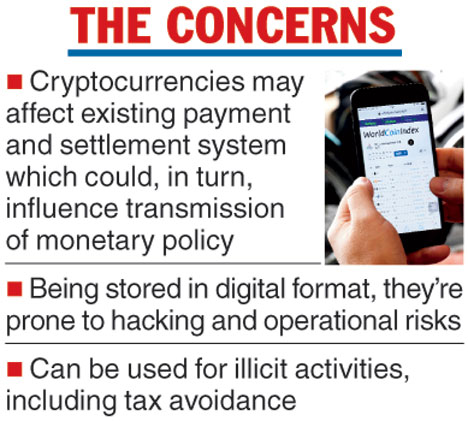

Significantly, the bitcoin-rich couple, the Bangkok Post wrote, “aimed to set up a permanent shelter out of any state territories by exploiting a loophole” in the UNCLOS. “The practice of attempting to establish micronations”, it reported, “are not recognised by world governments or major international organisations”. The practice is “expanding globally, particularly among those who become rich from cryptocurrency trading”.

If Elwartowski constructed the sea-house within Thailand’s territorial waters, he has violated the Thai criminal law. If not, the UNCLOS does not recognize his sea-house as “other installations” or “structures” given its non-statist nature. Yet, on April 21, 2019, Ocean Builder, a leading seasteading company, maintained that it “[has] been contacted by several countries” that appreciate the “potential” for “economic growth that their nation will receive once they have a wealth of new commerce and tourism off their coast.” The Thai government has now dismantled the sea-structure.

The Elwartowski affair is a smoking gun for what might also unfold soon in the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean.