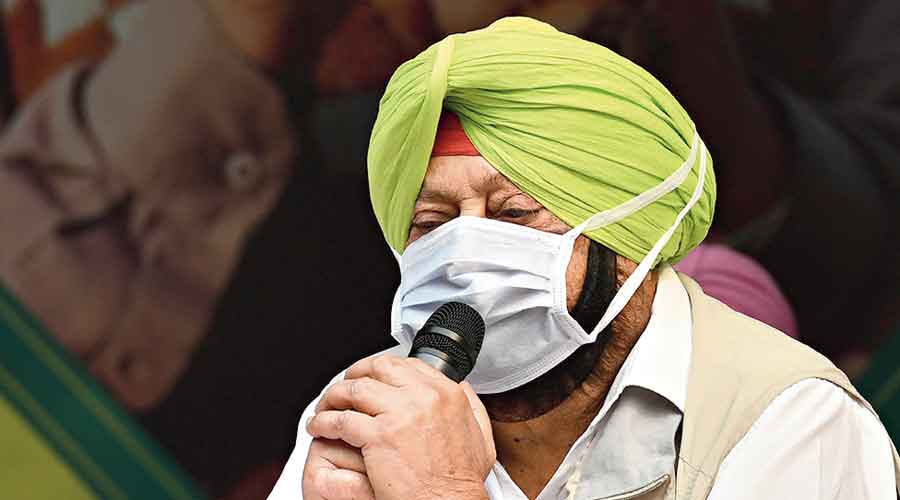

Navjot Singh Sidhu’s elevation to the post of state presidentship in poll-bound Punjab has been interpreted, not without reason, as a possible blunder. This is because Amarinder Singh, the party’s tallest leader and serving chief minister in the state, is unlikely to view Mr Sidhu’s rise kindly. The two have a history of animosity. Mr Sidhu had quit Mr Singh’s cabinet four years ago after a series of acrimonious disagreements: worse, he has not minced words since, and the chief minister has been the target of his acerbic comments. The Congress is notorious for internecine conflicts. Personal ambition has, more often than not, trumped party interests, leading to defections and even the fall of Congress governments. Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka, where the Congress lost power, are cases in points. There is concern that the squabble in Punjab could cost the party dear in an election that should have otherwise gone in the Congress’s favour. The simmering anger of Punjab’s agrarian community against the three agricultural laws passed by the Centre has effectively snuffed out the chances of the Bharatiya Janata Party. The Shiromani Akali Dal, usually a contender for power, has borne the brunt of collateral damage because of its association with the BJP, propelling the Aam Aadmi Party, another outfit with electoral ambitions, as the principal adversary against the Congress. Now, it seems that the Congress would have to contend with challengers outside and within. That cannot be reassuring for either the high command or the state unit.

Yet, could it be that there is a method in the madness? A cursory scan of developments within the Congress would reveal that the high command is, unlike in the past, no longer averse to regional, combative, vociferous leaders. Some of them — Mr Sidhu or, say, Nana Patole in Maharashtra — have even had stints outside the party. This, in turn, is perhaps indicative of two things. The weakness of the high command — the absence of a full-time president is one manifestation — is making it more reliant on regional leaders. The patronage for the latter also mirrors a broader turn in India’s political rhetoric. Politics is increasingly turning shrill, expanding the scope of leaders who believe in hurling fire and brimstone instead of reposing their faith in dignified, nuanced dialogue. The demise of the quiet, persuasive politician may be one of the consequences of Indian politics being enamoured of the cult of personality.