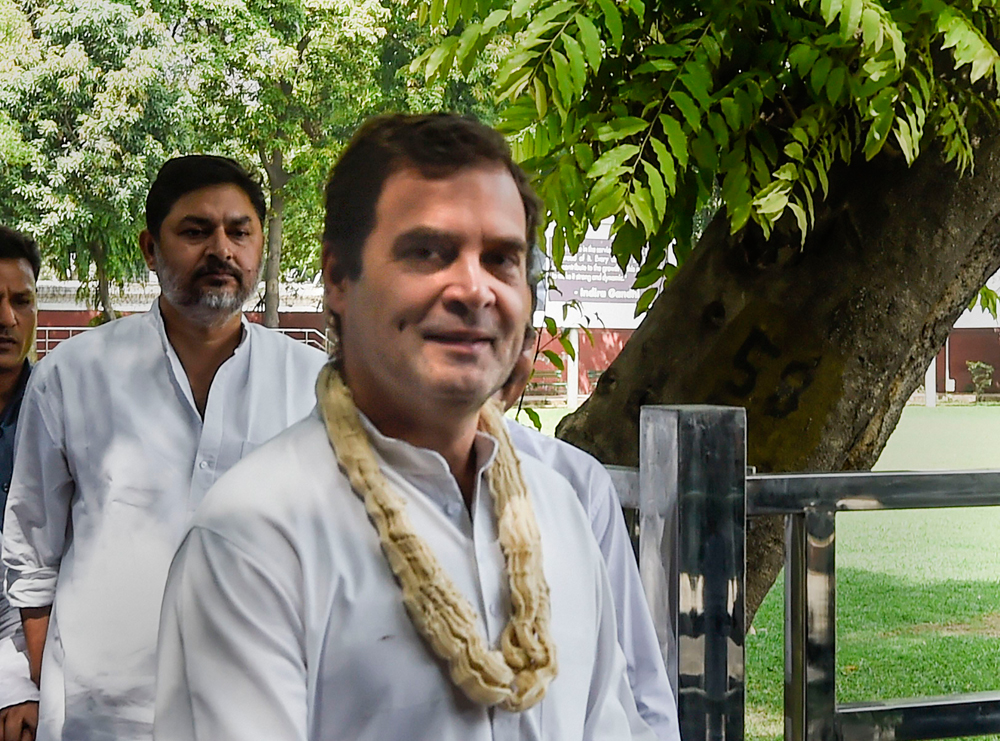

Two apologies have been among the ‘results’ of the elections just concluded. When you make a mistake, the judge, S.K. Kaul, said to Rahul Gandhi’s counsel, admit it. The matter was about the attribution of the “Chowkidar chor hai” remark to the Supreme Court. The mistake was admitted and an expression of regret followed. That having been found to be insufficient, especially because the word ‘regret’ had been placed in parentheses, a proper apology came. Better late than never is absolutely right when it comes to offering an apology.

Pragya Singh Thakur also apologized for her comments on Mahatma Gandhi’s assassin. Whether asked for or not, it was unconditional. “I apologize to the people of India,” the candidate for the Bhopal Lok Sabha seat said and added she held the Mahatma in esteem.

Were these two apologies, political, technical, meant to palliate the law? Cynics would say ‘Of course’. They would say Rahul Gandhi apologized to the court, not to the person aggrieved. They would say Pragya Singh Thakur, a terror-accused out on bail, could not have got away with what she said about a man who has been hanged for murder.

Be that as it may, there is no doubt that both suffered as a result of the words they used. And though both are now in the Lok Sabha, they are there with their hurtful words etched on their election campaigns. But it behoves us to take their apologies as earnest. And in the palimpsest of spoken words, treat the apology as overlaying and overcoming the reason for it.

Not having seen the two express their contrition, I have tried to visualize the expression and the acceptance of the apologies because the expression of apology is about grace, decency, civility, as is the acceptance of an apology. And, I thought of instances in history of public apologies, of remorse. And, contemplating them my imagination heard the erstwhile president, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, saying, in one of his great speeches, “Kshama virasya bhushanam,” forgiveness adorns the brave.

In the scales of grace, remorse and contrition, whether personal, stemming from an individual’s act affecting another individual or a great public transaction affecting several individuals, hundreds of thousands perhaps, weigh the same. It is as difficult to express, as difficult to accept in a private context as it is in the polis.

Asoka Piyadassi, from whose Lion Capital on the Sarnath pillar our national emblem is derived, gives us, in India, what may be called the first documented example of remorse. “Devanamapriya (the beloved of the gods), the conqueror of the Kalingas,” his Pillar Edict XIII says, “has remorse now, because of the thought that the conquest is no conquest, for there was killing, death or banishment of the people. That is felt keenly with profound sorrow and regret by Devanamapriya.” The carvers of Asoka’s edicts and of the Lion Capital, one wishes, had somewhere carved an image of Asoka apologizing to the Kalingas, with his hands folded if not with him kneeling. And the Kalingas accepting the royal apology, not without a wan resignation but, still, with grace. And if that imaginary sculptor had a sense of humour, he might have shown some of Asoka’s ministers watching with disapproval. That would have been some piece of art.

Wars are ballistic, of course. They are also redemptive.

During the Boer War in the South Africa of 1899-1902, when British atrocities on the Boers crossed the limits of civility even by war standards, W.T. Stead, pioneer of investigative journalism and editor of The Pall Mall Gazette, according to Gandhi, “publicly prayed and invited others to pray, that God might decree the English a defeat in the war”. Fellow journalists have raised a bas-relief monument to Stead near where he worked, in London’s Victoria Embankment.

Great God Google is a kind of carver, engraver. Thanks to Him, we know that immediately after the Trinity test at Los Alamos of the atom bomb, its ‘hero’, Robert Oppenheimer, took to the stage and clasped his hands together, it is said, “like a prize-winning boxer”, while the crowd cheered. His scientific genius had triumphed. But wisdom, atonement, were to come. He later said that at the time he saw the great explosion he thought of two verses from the Bhagavad Gita — one that spoke of divi surya-sahasrasya — the radiance of a thousand suns bursting at once in the sky, and kalo ’smi loka-ksaya-krt pravrddho — I am become death, the destroyer of the worlds. This was in the nature of what may be called realization of the diabolism that he had made.

On December 7, 1970, there took place, that day, an event which those in their seventies today would remember but those younger could well be informed about. It belongs to the same history of pain, remorse, atonement. The then German chancellor, Willy Brandt, was in Warsaw, Poland (then part of the Eastern Bloc) and visited the monument there to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. After laying his wreath, to the surprise of all present, he did something unexpected. He knelt. And remained silently in that position for a short time — half a minute — by the clock but an eternity in atonement. The photograph of that act is of the stuff of Michelangelo’s sculptures and indeed has been carved in stone on a tablet that stands by the monument. The sculptor of Kniefall von Warschau, Wiktoria Czechowska-Antoniewska is 90 this year.

But Brandt’s gesture has been vindicated by subsequent events. The German chancellor, Angela Merkel, recalled, during a visit to Japan in 2015, a 1985 speech by the then West German president, Richard von Weizsäcker, who called Germany’s wartime defeat, his own country’s defeat, a “day of liberation”. Extraordinary.

The name of Nobusuke Kishi, a war-crime accused but also post-war leader, former prime minister of Japan and maternal grandfather of the present prime minister, Shinzo Abe, is not one that would be instantly recognized today. Kishi said in 1957 to the people of Burma: “The Japan of today is not the Japan of the past, but, as its Constitution indicates, is a peace-loving nation.” And added: “We view with deep regret the vexation we caused to the people of Burma in the war just passed. In a desire to atone, if only partially, for the pain suffered, Japan is prepared to meet fully and with goodwill its obligations for war reparations.”

Barack Obama is not Willy Brandt and yet his visit as president of the United States of America to Hiroshima in 2016 matches Brandt’s as German chancellor to Warsaw in 1970. There was no kniefall but he spoke of a ‘fall’. “Seventy one years ago,” Obama started, invoking Lincoln’s “Four score and...” and then said: “... on a bright cloudless morning, death fell from the sky and the world was changed. A flash of light and a wall of fire destroyed a city and demonstrated that mankind possessed the means to destroy itself.” We could say Obama has read and interiorized his Oppenheimer. The White House has had, can have, reading men.

Some of these thoughts I shared with a gathering in London last month, at a lecture in memory of M.K. Gandhi. The visit of the US president, Donald Trump, to London in which he described London’s mayor, Sadiq Khan, in terms that were unbelievable happened the week that followed. He has stayed un-repentant. Will he ever in his life regret what he said? I doubt it. The loss will not be Khan’s.

Gandhi’s admission of a “Himalayan miscalculation” after the Kheda satyagraha in 1919 had found satyagrahis wanting in discipline is well-known. He gave, in that statement, a simile drawn from the science of optics: “I have always held that it is only when one sees one’s own mistakes with a convex lens, and does just the reverse in the case of others, that one is able to arrive at a just relative estimate of the two.”

Where is the optician who can fit those two lenses in politicians’ eyes? Where dwells the politician who will see his mistakes as larger and his opponent’s as smaller? ‘Not in South Asia for sure,’ I can hear the cynic say. But pause a moment. Hear Bhutan’s prime minister, Lotay Tshering, speaking on June 16: “If India and Pakistan don’t work together for this region, nothing can move ahead. So my prayers and wishes from our deeply spiritual country are for the leaders in this region to go ahead together.” I can hear Asoka’s voice in those words.