Speaking in Parliament after unveiling a portrait of Lokmanya Tilak in 1956, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru stated: “We have, to my right here, the picture of Dadabhai Naoroji, in a sense the Father of the Indian National Congress. We may... in our youthful arrogance think that some of these leaders of old were very Moderate, and that we are braver because we shout more. But every person, who can recapture the picture of old India and of the conditions that prevailed, will realise that a man like Dadabhai was, in those conditions, a revolutionary figure. If I say that of Dadabhai Naoroji, how much more I can not say about Lokmanya?”

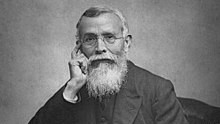

There cannot be a better introduction for the present generation to ‘The Grand Old Man of India’ whose 104th death anniversary falls today. Amongst the tallest nationalist leaders of the pre-Gandhi era of the Independence movement, Naoroji was thrice the president of the INC. Although A.O. Hume was the founder of the INC, and W.C. Bonnerji its first president, yet Nehru chose to refer to Naoroji as virtually the father of the INC. This may be because many years before the INC was founded in 1885, Naoroji had founded the East India Association in 1866 in London and, later, the Bombay Presidency Association in January, 1885. This organization, along with the Indian National Conference founded in 1883 in Calcutta by Surendranath Banerjea, became the precursor of the INC.

Born in 1925 in a priestly Parsi family, Naoroji left for England in 1855 to join Cama’s firm in London as a business partner. He got so involved in political activities focusing on poverty in India that he contested the election for the House of Commons in 1886 but lost in spite of the fact that Florence Nightingale canvassed for him. He, however, was successful in 1892 when he was returned from Central Finsbury constituency, representing the Liberal Party. As he had won by a margin of only three votes, the Conservative prime minister, Lord Salisbury, demanded a recount. Salisbury was right; there had indeed been an error in counting — Naoroji had won by five votes, becoming the first Asian to become a member of the British Parliament. While in England, Naoroji became famous for highlighting the unfavourable economic consequences of British rule in India. In his speeches and writings, especially in Poverty and Un-British Rule, he gave expression to his theory of drain of wealth and how it was responsible for poverty in India.

It was during his stay in London that the two future ‘fathers’ of two nations — Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and Mohammed Ali Jinnah — were to draw inspiration from Naoroji who had become very popular amongst the Indian community, especially among the youth and students. Jinnah, along with Chittaranjan Das, not only campaigned for Naoroji in the elections but also became his private secretary for a number of years. Gandhi met Dadabhai’s granddaughter, Gosi, who wrote to her grandfather, then in India: “He [Gandhi] simply worships you.” In one of his speeches Gandhi pronounced Dadabhai as a rishi from whom “I myself and many like me have learnt the lessons of regularity, single minded patriotism, simplicity, austerity and ceaseless work from this venerable man.” The Mahatma acknowledged his debts to Naoroji’s economic writings for teaching him about the horrific dimensions of Indian poverty. So did the next generation of nationalist leaders. Writes Dinyar Patel in his biography of Naoroji: “Languishing in British jail in 1934, Jawaharlal Nehru reflected on his exposure of Indian poverty, which the future Prime Minister claimed, ‘served a revolutionary purpose and gave a political and economic foundation to our nationalism’.” Sarojini Naidu believed that he “kindled the torch of freedom of India”. Indeed he did. Naoroji inarguably ranks along with Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Gopalkrishna Gokhale as the three greats Indians of the pre-Gandhi era of the freedom struggle that emerged from the birth of INC 136 years ago.