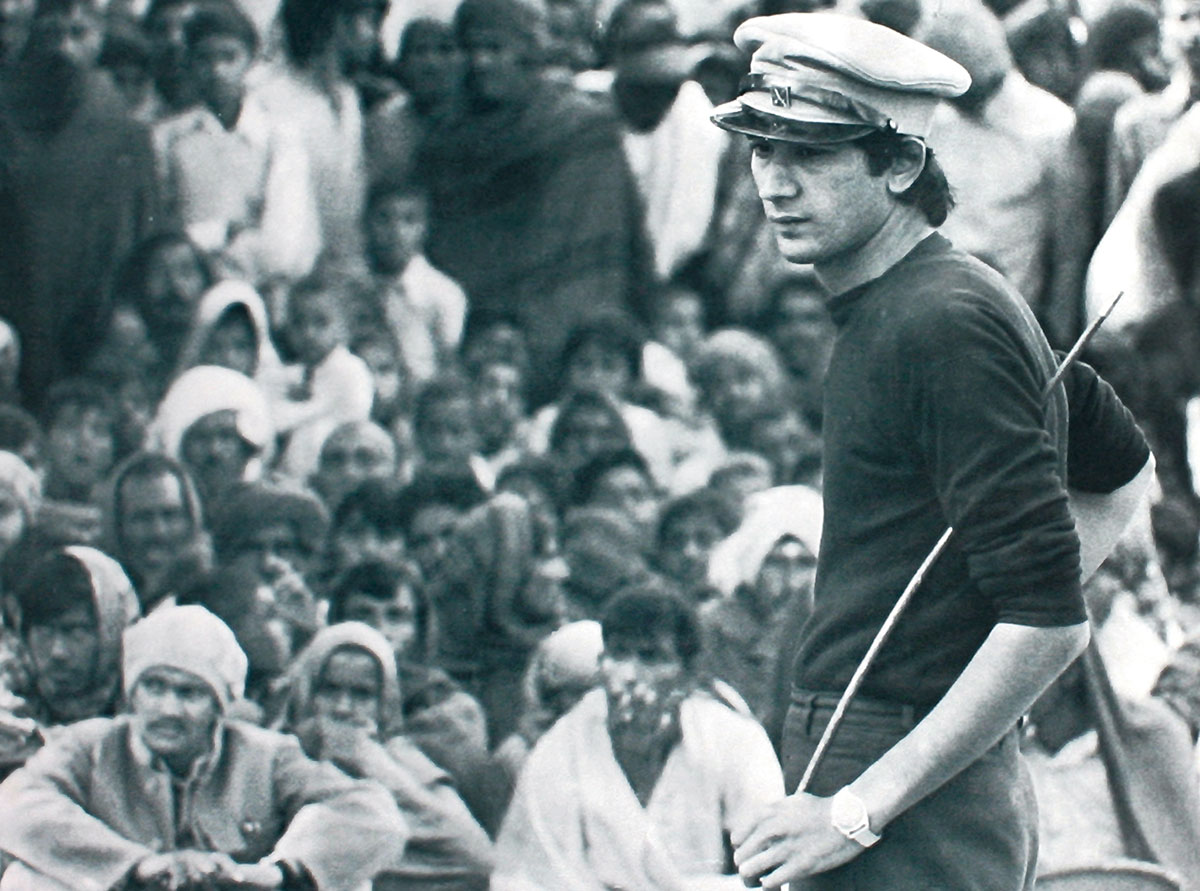

Thirty years ago, there died a man. On January 1, 1989, Safdar Hashmi and other members of the Jan Natya Manch, the street theatre group of which he was the brain and the soul, were attacked at Sahibabad — the industrial township in Ghaziabad, near Delhi — while they were staging a play called Halla Bol. With characteristic courage, Hashmi took upon himself much of the violence. The following day, he succumbed to his injuries.

Hashmi was a prominent communist playwright. He specialized in educating and organizing the working class and the middle classes by means of theatre performances. As for the identity of the killers, the available evidence pointed to goons who were allegedly patronized by the Congress and the Indian National Trade Union Congress.

For once, the national media called a spade a spade. Wide coverage was given to the dastardly act, and people from all walks of life condemned the murder of this extraordinary young man (he had turned 34). A little more than a week after Hashmi’s death, Shabana Azmi stunned delegates attending the 12th International Film Festival of India in New Delhi when she went on stage and accused the Congress of claiming to promote art and culture on the one hand and, on the other, doing away with cultural activists who sought to uphold working class ideals in a democratic manner. The then information and broadcasting minister, H.K.L Bhagat, was heard refuting Azmi’s allegations but very few people in the audience appeared to take his word seriously. That year, street theatre groups observed April 12, the young martyr’s birthday, as Jan Natya Divas, celebrating the ideals that Hashmi held dear. His plays were translated into different languages and presented before audiences comprising the poor and the marginalized. The middle classes also joined in at places, but their enthusiasm was tempered by caution.

It is pertinent to ask anew why this extraordinary citizen and artist was eliminated. He was murdered by the organized mafia because he wrote and spoke well and was an able organizer, representing in word and deed a certain culture of resistance that was offensive to the mandarins of status quo. Hashmi was opposed to living the life of an ivory-tower intellectual; he was vulnerable because he was a visionary; he could be felled because he was unafraid of exposing himself to danger for the things he believed in. He was prepared to suffer for his principles; and suffer he did, meeting an end covered in blood and honour.

The resounding success of the movement led by CITU in Sahibabad in late 1988 owed not a little to the performances put up under Hashmi’s leadership. Sahibabad had been an INTUC stronghold. It was alleged that the goons had struck when things seemed to be slipping out of their grasp.

Hashmi was, to put it somewhat loftily, a child of destiny. He could have chosen a less principled path, living to a ripe old age and dying in comfort of natural causes. A distinguished alumnus of St Stephen’s College, Hashmi was born to wealth and high social standing. He could have been a member of the Indian Administrative Service or that of the boxwallah fraternity for the asking. But no, he had different plans for himself. As is clear from the trajectory of his brief but momentous life, he wanted to be of real value to his hapless countrymen; to place his gifts of head and heart at the service of the weakest in society.

After teaching for a while, followed by a stint as press officer at the West Bengal Information and Cultural Centre in New Delhi, Hashmi gave up all thoughts of a conventional career to devote himself exclusively to raising social awareness by means of street theatre. He built his own team of actors and actresses, wrote plays and poetry, composed songs and for years together — under the banner of the Jan Natya Manch — went from one factory to another, from one mohalla to the next, one college to another, trying to instil class consciousness into those who were willing to lend a ear. His was a mission to get as close as he could to the labouring classes in particular, exhorting them to unite and struggle as one, democratically and non-violently.

Hashmi was too astute a student of history and too perceptive an observer of the social and economic realities of his time to not realize that given the existing character of the Indian ‘system’, violent confrontation with the propertied and the privileged would amount to a battle lost before it had even begun. That, in spite of his sagacious understanding of conditions on the ground, violence visited him the way it did carries a lesson immersed in sadness and irony.

In a sense, Hashmi’s was a death foretold, both moving and enlightening, reminding us of a galaxy of tragic heroes belonging to a wide range of references, including the Mahabharata and Greek tragedies.